CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss the advantages of CBCT view for orthodontic diagnosis.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize the radiation differences between CBCT scans and panoramic radiographs.

- Identify anatomy that can be distinguished on slices and volume CBCT views.

- Recognize some usual and unusual anatomical discoveries on CBCT scans.

- Read about some details that can be viewed on CBCT regarding degenerative joint disease.

- Identify when it may be necessary to outsource the scan for a reading.

Dr. Andrew Trosien discusses the benefits of a CBCT view

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is becoming much more common in dentistry. A few years ago, it was unusual to get images from a colleague’s CBCT machine, whereas today it is not unusual for a few doctors in a given town to have a CBCT machine. But unless you recently graduated from orthodontic residency, you haven’t had access to much training in the interpretation of CBCTs.

Further compounding the issue is the fact that much research on and with CBCTs has occurred within the last few years. So forward-looking practitioners would be wise to learn about how to approach a CT scan, and what to look for, what to measure, and what it means.

Further compounding the issue is the fact that much research on and with CBCTs has occurred within the last few years. So forward-looking practitioners would be wise to learn about how to approach a CT scan, and what to look for, what to measure, and what it means.

Some debate remains as to whether CBCT should be used only for select patients or as a complete replacement for traditional orthodontic X-rays. Much of this dispute revolves around the radiation doses of CBCT and the fear that patients are subjected to excessive levels of CT radiation.  However, these fears are unfounded. While a traditional, hospital-based spiral CT of the head give a dose of 860 microsieverts (the equivalent of more than 45 panoramic X-rays), the cone beam CT gives much less.1 The difference is related to the design of the machine, and the difference between the cone and spiral beams. For reference, the extended field of view (full head) on an i-CAT, with the traditional .3 mm3 voxel size at 8.9 seconds, results in a dose of 74 microsieverts, which is less than four panoramic radiographs.1 And for a low dose “progress” scan, with a 0.3 mm3 voxel and 4.8 seconds, the dose is lower than 1.5 panoramic radiographs.1 The amount of radiation in a full-mouth series with F-speed film is the equivalent of nine panos,1 while the CBCT gives an amazing amount of information with minimal radiation dose.

However, these fears are unfounded. While a traditional, hospital-based spiral CT of the head give a dose of 860 microsieverts (the equivalent of more than 45 panoramic X-rays), the cone beam CT gives much less.1 The difference is related to the design of the machine, and the difference between the cone and spiral beams. For reference, the extended field of view (full head) on an i-CAT, with the traditional .3 mm3 voxel size at 8.9 seconds, results in a dose of 74 microsieverts, which is less than four panoramic radiographs.1 And for a low dose “progress” scan, with a 0.3 mm3 voxel and 4.8 seconds, the dose is lower than 1.5 panoramic radiographs.1 The amount of radiation in a full-mouth series with F-speed film is the equivalent of nine panos,1 while the CBCT gives an amazing amount of information with minimal radiation dose.

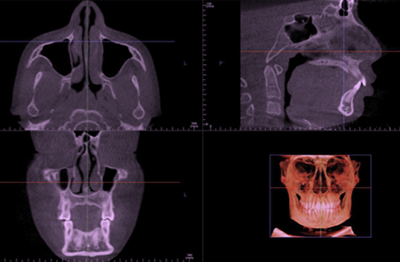

Fundamentally, a CBCT can be viewed in two different ways: As slices or as a volume. It’s not a matter of which you prefer — both are important. Certain features are best viewed in slices, while others are best viewed in the volume. Initially, when viewing a CBCT as part of a formal work up, most doctors will start with the slice data (Figure 1). The idea is to scroll through the volume, “slice by slice,” and look for anything out of the ordinary. It takes a while to identify what is considered normal, and what is actually abnormal. When starting with the coronal slice (Figure 2), we can scroll through and see the maxillary sinuses, the nasal septum, the nasal turbinates, the ethmoid sinuses, and the ear canals. (Of course, most anatomy can be seen with this view, but anatomy like the teeth, the maxilla and mandible, condyles, etc., are more easily seen in other CBCT views.)

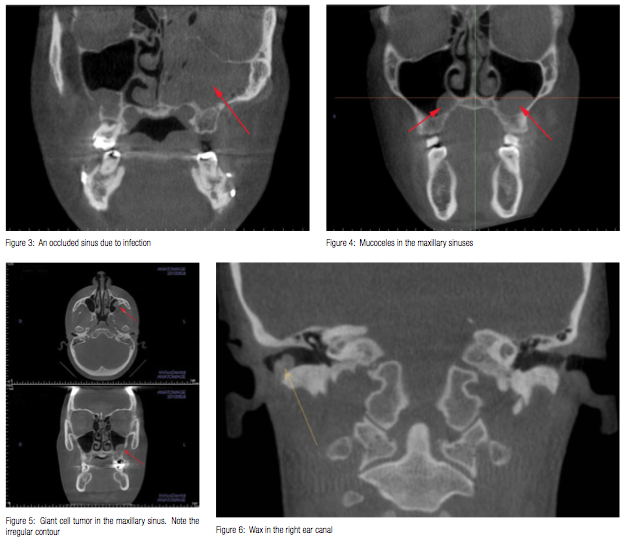

The maxillary sinuses can be completely occluded if the patient has a cold (Figure 3)or can have a thick lining, showing inflammation. There may also be what appears to be a small “balloon” in the sinus, which is a harmless mucous retention cyst (Figure 4). It is the balloon-like appearance that is indicative of a mucous retention cyst. In contrast, if it does not have that smooth, “inflated” round appearance, it may be a tumor (Figure 5) and should be reviewed by a radiologist. Surprisingly, it is not unusual to see a really small maxillary sinus, which is just an aplasia, and typically needs no intervention.

The ear canals should be generally open, though it is not atypical to see an accumulation of wax (Figure 6). However, if anything is seen in any of these areas that looks particularly radiopaque, it’s probably something that should not be there, and should be checked out — like this piece of metal from the tip of forceps used to remove an ear tube (Figure 7).

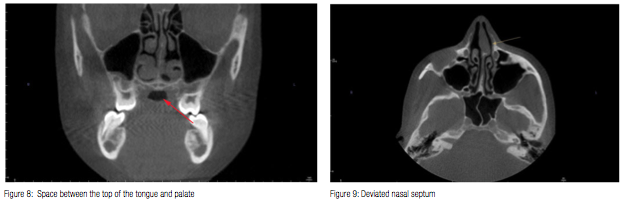

The coronal view also shows the tongue. While not diagnostic of a problem, it is worth noting if there is a space between the top of the tongue and the palate in this view (Figure 8). It has been shown that expanding the maxilla creates a larger volume for the tongue to occupy, allowing it to migrate away from the back of the throat, opening the airway.2 A low tongue posture with the subsequent narrow maxilla may lead to a treatment plan involving maxillary expansion.

Next, viewing the volume from the axial view, we can scroll through the frontal sinuses, the ethmoid sinuses, the nasal septum, and the maxillary sinuses. Sometimes an ordinary-looking structure in the coronal view of the maxillary sinuses can be viewed in the axial view for more information. The axial view offers the best view of the nasal septum. A deviated septum is not atypical and requires nothing more than informing the patient or the parent (Figure 9).

The sagittal view gives the best view of the airway. The adenoids, soft palate, and base of the tongue are all structures that can occlude the airway. While we cannot do any sort of volume measurements on this sagittal view, it does give an indication of what structures are responsible for the airway occlusion.

The volume view gives an overall assessment of the symmetry and structure of the skull and jaws. This view allows us to check the maxilla and mandible for supernumerary teeth, ectopic teeth, missing teeth, etc. We can toggle the view setting to show just osseous tissue to see the level of the bone around the teeth, as well as its thickness facially and lingually to them. Switching to an airway view allows measurement of the pharyngeal airway volume (Figure 10). The CBCT provides a reliable and accurate airway volume measurement.3 If the minimal cross-sectional area of the pharyngeal airway is below 50 mm,2 then the patient is at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Between 50 and 100 mm2 indicates moderate risk, and greater than 100 mm2 is low risk.4,5

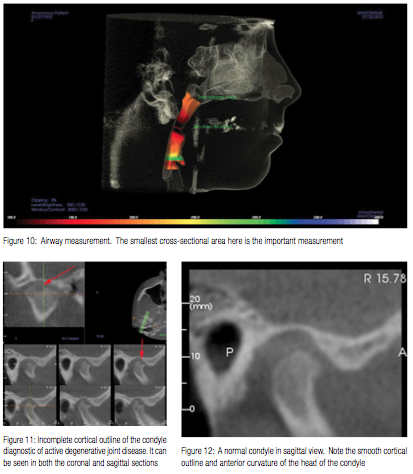

The CBCT offers a superior way of assessing the condyles. Prior to CBCT, a tomographic series was routinely used to view the joints, and the quality of the images was much lower than what we now receive from a CBCT. As research continues with CBCT, we should gain more knowledge about the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). The condyles are best viewed in their own dedicated slice window.

The principal abnormality that one looks for in TMJs is degenerative joint disease (DJD). DJD destroys the articular tissues and occurs when the remodeling capacity of the articular tissues is exceeded by functional demands. The primary diagnostic feature is a lack of cortical outline along the superior aspect of the condyle. A cessation of the cortical outline, or cortical fuzziness, indicates active degeneration (Figure 11).

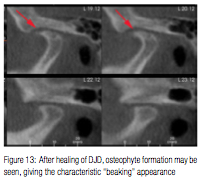

Because CBCT screening includes an analysis of the TMJs, it is worth reviewing the continuum of temporomandibular dys-function. A normal joint presents a smooth, rounded cortical outline with an anterior cant (Figure 12). Once a disc displacement develops, some sclerosis and flattening along the superior anterior aspect of the condyle can be seen. Next, the condyle develops further flattening, and finally results in a non-reducing disc. At this point, erosions that characterize active DJD often develop. As the joint attempts to heal, bone will accumulate on the margin of the condyle, giving the characteristic “beaking” appearance of osteophyte formation (Figure 13). At this point it is not unusual to see subchondral bone cysts, which are characterized by a radiolucency below the cortex of the joint.6

From an orthodontic perspective, a patient with a history of DJD is less troublesome than a patient with active DJD. In other words, finding beaking and reduced condylar height should not be as alarming as seeing an incomplete cortical outline, which as the hallmark of DJD, contraindicates orthodontic treatment. Orthodontic therapy in the presence of DJD will exacerbate condylar resorption much like orthodontic treatment in the presence of active periodontal disease will exacerbate alveolar bone loss. If a patient has active DJD, the orthodontist may choose to wait (in the absence of symptoms) or to make a centric relation bite splint (for the symptomatic patient). Resolution of the disease can take months and needs follow-up with periodic CBCT scans.

From an orthodontic perspective, a patient with a history of DJD is less troublesome than a patient with active DJD. In other words, finding beaking and reduced condylar height should not be as alarming as seeing an incomplete cortical outline, which as the hallmark of DJD, contraindicates orthodontic treatment. Orthodontic therapy in the presence of DJD will exacerbate condylar resorption much like orthodontic treatment in the presence of active periodontal disease will exacerbate alveolar bone loss. If a patient has active DJD, the orthodontist may choose to wait (in the absence of symptoms) or to make a centric relation bite splint (for the symptomatic patient). Resolution of the disease can take months and needs follow-up with periodic CBCT scans.

Clinicians should note that the shape of the condyle is not the issue as much as the presence or absence of cortical outline. A bifid condyle (Figure 14), while having a divot in its center, is a normal variation, has a continual cortical outline, and does not indicate DJD.

Given the nature of degenerative joint disease and the difficulty for novice CT readers to confidently diagnose it, there are a number of services for outsourcing the reading. BeamReaders, started by Dr. David Hatcher, is the most well-known of these. Some doctors choose to upload every CBCT taken for a BeamReaders report. Others choose to upload those images that have areas of suspicion. These services have a staff of doctors with a significant amount of experience and provide an abundance of knowledge.

Given the nature of degenerative joint disease and the difficulty for novice CT readers to confidently diagnose it, there are a number of services for outsourcing the reading. BeamReaders, started by Dr. David Hatcher, is the most well-known of these. Some doctors choose to upload every CBCT taken for a BeamReaders report. Others choose to upload those images that have areas of suspicion. These services have a staff of doctors with a significant amount of experience and provide an abundance of knowledge.

The most difficult thing to learn when interpreting CBCT scans is the variations of “normal.” After viewing a few dozen scans, doctors will develop a familiarity with the different variations of normal. As with any new technology, orthodontists should avail themselves of literature, courses, and hands-on experiences to enhance their knowledge and interpretive skills with CBCT. Practice makes perfect only when the practice is perfect.

References

- Ludlow JB, Ivanovic M. Comparative dosimetry of dental CBCT devices and 64-slice CT for oral and maxillofacial radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(1):106-114.

- Iwasaki T, Saitoh I, Takemoto Y, Inada E, Kakuno E, Kanomi R, Hayasaki H, Yamasaki Y. Tongue posture improvement and pharyngeal airway enlargement as secondary effects of rapid maxillary expansion: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143(2):235-245.

- Ghoneima A, Kula K. Accuracy and reliability of cone-beam computed tomography for airway volume analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35(2):256-261.

- Avrahami E, Englender M. Relation between CT axial cross-sectional area of the oropharynx and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in adults. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16(1):135–140.

- Ogawa T, Enciso R, Shintaku WH, Clark GT. Evaluation of cross-section airway configuration of obstructive sleep apnea. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(1):102–108.

- McNeil C, ed. Science and Practice of Occlusion. Chicago, IL: Quintessence; 1997.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores