Editor’s intro: Dr. Klifford Kapus discusses the pros and cons of two-phase treatment and the importance of taking the parent’s and child’s circumstances into account.

Dr. Klifford T. Kapus discusses a case presentation

Perhaps the most dramatic change in my practice philosophy since I achieved my orthodontic certification in 1999 has been my stance on early interceptive Phase I treatment of patients in the mixed dentition. As residents, my classmates and I devoted an entire Wednesday morning to a Phase I clinic each week. There we learned about the advantages of early treatment and the benefits for the patient. For the most part, I still agree with those teachings, and I don’t hesitate to recommend early treatment for a patient with a developing problem who would benefit from a proactive approach. However, I now believe that there is a very broad continuum between the reactive and proactive stance, and where each individual practitioner places himself/herself along that continuum is a personal choice and part of the art of orthodontics. I still strongly recommend that all patients get screened for possible Phase I treatment by ages 7 to 8; however, I have personally become much more conservative about the patients for whom I recommend it.

Early consultations: ranking patients into one of three categories

1. The absolutely need-to-do Phase I patients

This is the arm-waving, up-on-a soapbox, “I’d surely do this if it were my child” patient. These are the children who have partial anterior crossbites with the strong potential for recession and attachment loss or uneven attrition of the enamel. They are the ones who are an absolute train wreck of crowding where serial extraction procedures and eruption guidance are going to massively simplify a child’s treatment and finish him/her at a younger age with a better final result. These are the patients for whom you recognize that NOT doing a Phase I is going to negatively impact their overall final results or oral health.

2. Patients with questionable hygiene, extreme timidity, or special needs

For these patients, I would lean toward treatment, but something about their behavior causes me to doubt making a strong recommendation. Sometimes the treatment is right for the patient, but the patient isn’t right for the treatment. In situations like these, I will discuss my reservations with the patient’s parents, and if I feel as though we can proceed, we will.

3. “Parents’ choice” Phase I patients

The patient perhaps has mild-to-moderate crowding or a small diastema, and the parents explain that they are awfully and terribly concerned about these features and simply cannot stand to leave it and look at it for several years without intervention. Sometimes the patients themselves are concerned; perhaps they have been teased at school about their appearance. In situations like these, I am happy to provide treatment; despite feeling as though I will get a better result clinically, there is some valid psychosocial benefit to the patients or parents and no negative impact from the treatment.

Case presentation

The case I am presenting is a typical two-phase treatment plan, but it demonstrates a few interesting lessons that I have learned over the years.

- Early removal of C’s to provide immediate space for the eruption of the 2’s and alignment of the anterior teeth does not eliminate the possibility of cuspid impaction.

- Strategic timing of the removal of an obstructive tooth can and often does lead to spontaneous correction of cuspid impactions

- Extraction of bicuspid teeth to address crowding does not absolve the risk of molar impaction

- Uprighting impacted second molars while the patient is still in orthodontic treatment is one of the most positive functional benefits we can offer our patients.

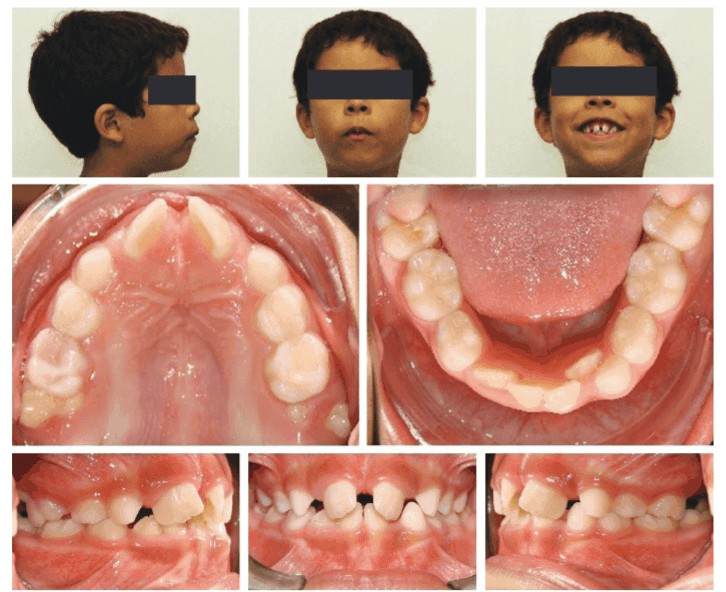

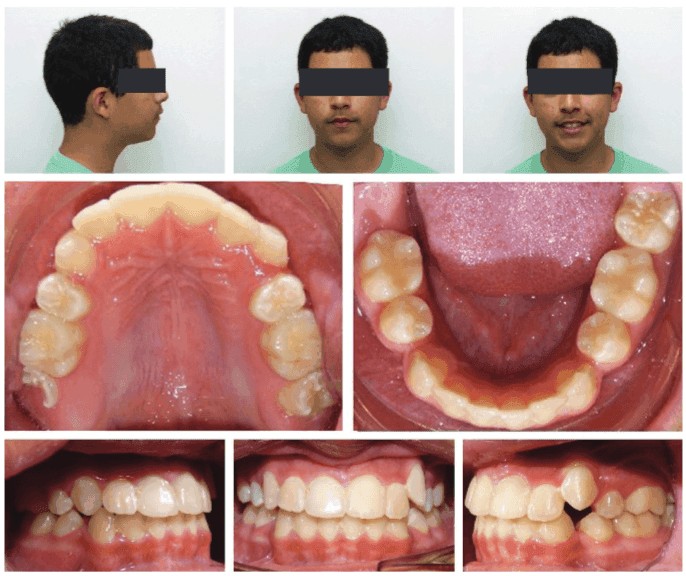

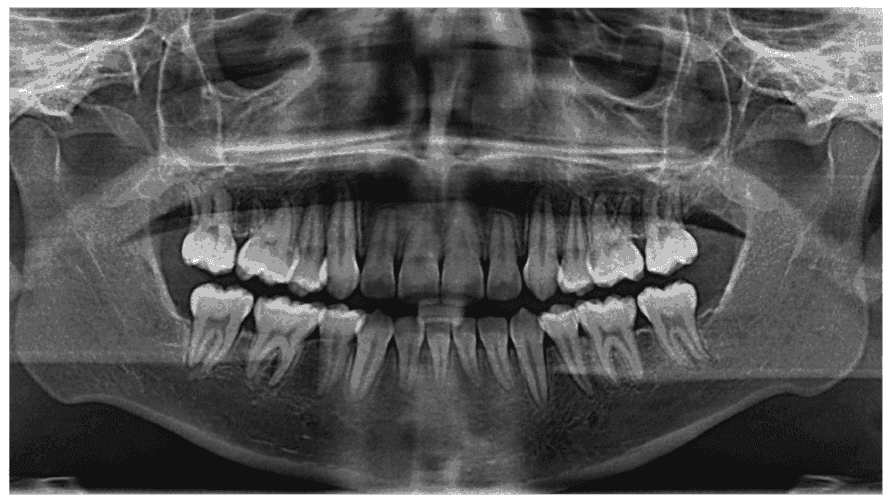

The patient originally presented for consultation at age 7 years 6 months with chief complaint of anxiety about the appearance of his upper central incisors. The pediatric dentist had referred him because of ectopic eruption of the upper first permanent molars. I noted severe upper/lower crowding and proclination of the anterior teeth, early loss of the lower right primary cuspid (R), mild lip incompetence, and hyper-mentalis strain. I strongly suspected the patient would eventually require extraction of all first bicuspids not only to address the severe arch length discrepancy, but also to minimize the risk of impaction of unerupted teeth. Note that the upper left permanent cuspid (No.11) shows no evidence of impaction on the initial panoramic provided by the pediatric dentist.

Phase I treatment (Figures 1-3)

My recommendation was Phase I interceptive orthodontic treatment with extraction of remaining primary cuspids C, H, and M and partial fixed appliances on the upper and lower teeth. Goals of Phase I therapy included alignment of the upper/lower incisors. Treatment ran longer than normal for a Phase I (I typically prefer to stick to a 14-16 month maximum duration) due to the slow eruption of the upper lateral incisors. The patient completed treatment at 19 months with end on molars. Despite the early loss of the upper E’s during treatment, I was able to utilize fixed appliances to prevent mesial drift of the upper 6’s. The upper and lower incisors were too proclined for my tastes, but I was hopeful that the eventual extraction of the 4’s would provide another opportunity to retract them. Retention was provided by the use of upper and lower Hawley retainers.

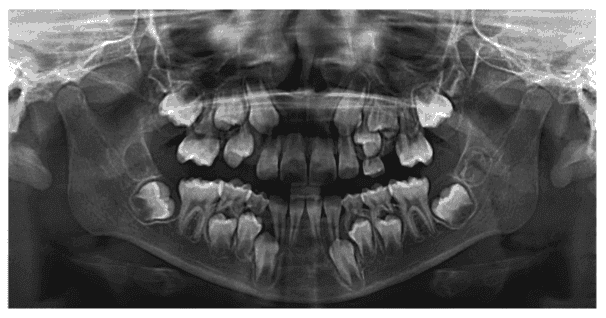

I continued to monitor the eruption of the permanent teeth every 12 weeks. At 2 years into retention (age 11 years 1 month), when I could see that the first permanent bicuspids were present and accessible, I took a progress panoramic and noted that the lower right 7 (No. 31) was impacted as was the upper left cuspid (No. 11). At this point I was faced with a choice. I did not feel that placing the patient back in fixed appliances at this point was appropriate. Therefore, the only proactive move I had available was to recommend the extraction of all four permanent first bicuspids to facilitate the eruption of the remaining permanent teeth.

Seven months later after the extractions had been completed, I recalled the patient for a routine retainer-check appointment and took another panoramic X-ray to see how the upper left cuspid was responding. I was pleased with the amount of spontaneous self-correction but still felt that delaying the start of Phase II was prudent in order to minimize the amount of time spent in active therapy.

We continued to monitor eruption, and the patient requested that we delay starting treatment until after his 8th-grade band sessions ended at school. He played trumpet and was rightly concerned that fixed appliances would interfere with his embouchure.

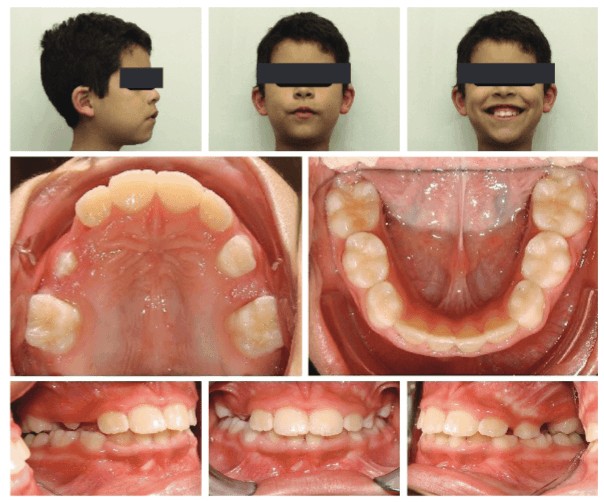

Finally, by age 14 years 5 months, he was ready to start, and we were all thrilled to see that what I had previously thought to be a definitive impaction of the upper left permanent cuspid resolved itself without any interference, save the otherwise needed bicuspid extractions.

Phase 2 treatment (Figures 4-6)

We proceeded with Phase II treatment, which included fixed appliances on the upper/lower teeth (In-Ovation® C self-ligating brackets, Dentsply Sirona). Our goals were to align the upper/lower teeth, close any residual crowding and then re-assess the impaction of the lower right second molar (No. 31). Unfortunately, despite our success with the cuspid, the lower second molar did not self-resolve, and 7 months into Phase II treatment we referred to a local oral surgeon to extract all third molars and expose the crown of the lower right second molar. Once the crown of this tooth became accessible, we bonded a molar tube and uprighted it. This required repositioning of the tube bracket more than once, but eventually the molar was placed in proper position. Treatment was completed 24 months after starting the Phase II treatment.

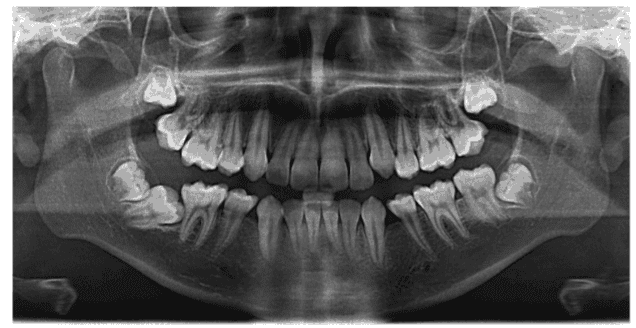

Final results (Figures 7-8)

The final results are good, although I feel that the anterior teeth are still somewhat proclined. There is evidence of root tip blunting on the final panoramic, so I was hesitant to apply too much additional torque, and the patient and parents felt that the profile and inclination of the teeth were acceptable.

De-impacting second molars is an enormously beneficial service we are able to offer our patients and represents possibly one of the biggest functional improvements we can provide as orthodontic specialists. And yet this often receives the least amount of attention and fanfare. Patients don’t often notice that their second molars are in poor position, and while they may not perceive the extent of the improvements you can provide, this is a huge opportunity for open discourse with the patient and their parents. It’s important to explain that leaving a second molar impacted beneath the neighboring first molar can lead to decay and/or loss of one or both molars in that quadrant.

Key takeaways

- Two-phase treatment is appropriate at least some of the time, but how you prioritize patient “need” for Phase I is an individual choice.

- Removal of the obstacle preventing eruption of upper cuspids often leads to self-correction of an ectopic eruption.

- Extraction of bicuspids does not frequently provide sufficient room to de-impact second molars.

- De-impaction and uprighting of second molars represent an enormous functional benefit to our patients, and this benefit should be thoroughly conveyed to patients and their parents.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores