Drs. Dara L. Rinchuse and Donald J. Rinchuse reflect on delaying orthodontic treatment for very young patients

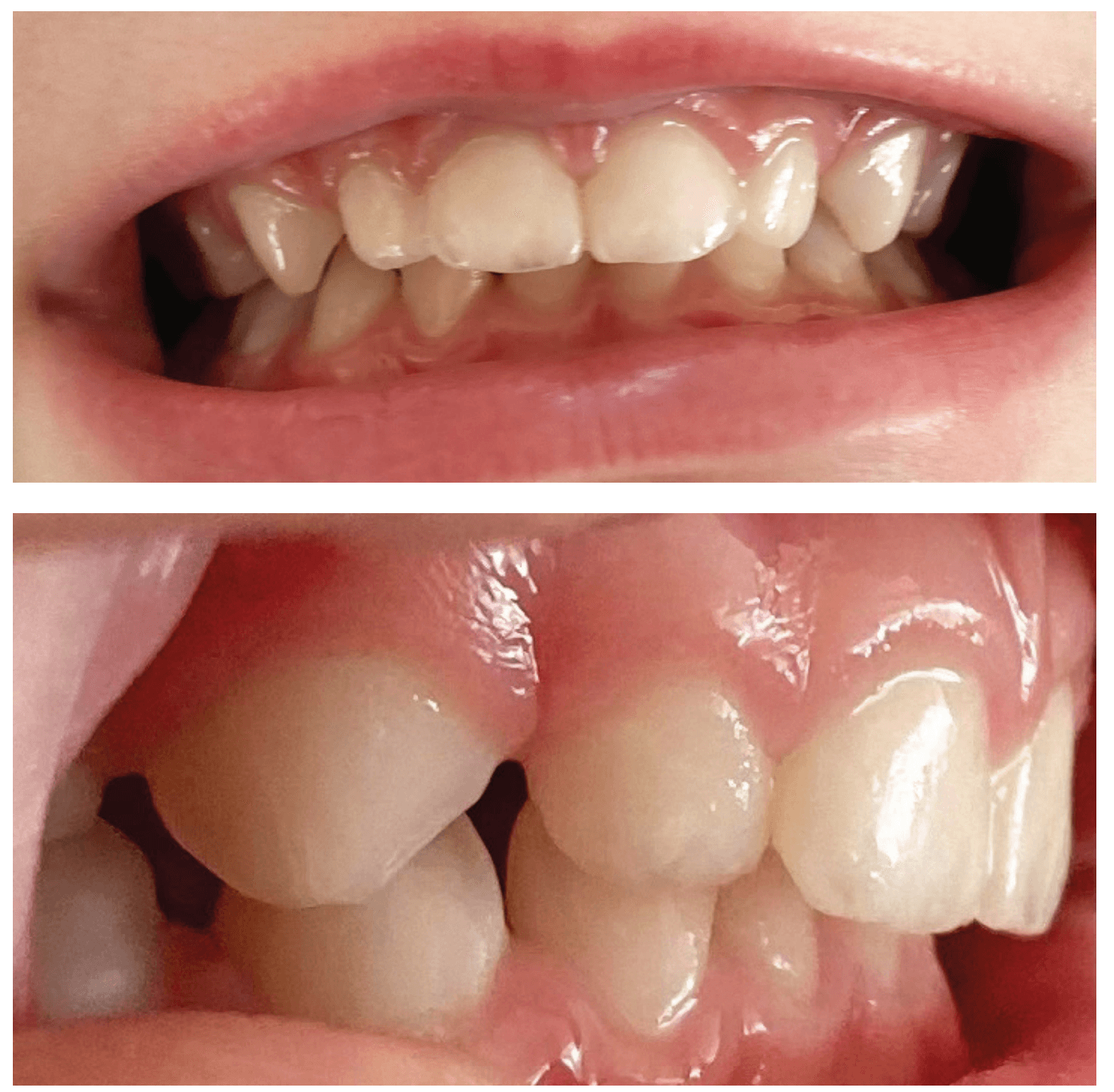

The primary author’s 3-year-old daughter, JoJo (and co-author’s granddaughter), had used a pacifier (“binky”) since birth. The pacifier (Philips Avent Soothie) adversely altered JoJo’s oral facial complex creating severe maxillary anterior protrusion. Family photographs document the progress of JoJo’s case from pacifier use (Figures 1A-1C) to months afterwards when the pacifier was discontinued (Figures 2A-2B). Figures 1A-1C show the profound untoward effects the pacifier had on her dentition causing severe maxillary protrusion (Class II division 1 malocclusion with a large overjet). After stopping the pacifier at age 3 years, 4 months, her malocclusion returned to a rather normal state 4 months later (Figures 2A and 2B). Of note, JoJo had a tongue thrust while using the pacifier, and the tongue thrust disappeared after discontinuing the pacifier. Notably, JoJo’s malocclusion corrected without any kind of treatment. If JoJo had had treatment, the outcome of her bite correction could have reasonably been assumed to be due to an orthodontic intervention rather than a natural occurrence, i.e., the return to homeostatic balanced oral soft-tissue forces.

Discussion

Observations in clinical practice can be misleading if a practitioner does not consider and account for clinical results being due to factors other than clinical treatments. JoJo’s case illustrates why controls are necessary in clinical experimental research. Importantly, research controls serve as baselines that allow researchers to compare the effects of experimental treatments against subjects who did not receive treatment. Further, control groups help by eliminating or reducing the effects of confounding factors, account for placebo effects, measure natural changes, reduce bias, establish causality, and enhance validity.1

JoJo’s case brings to mind several additional considerations. For one, are many of the orthodontic phase I treatments necessary? Are many orthodontic problems self-correcting, particularly for very young children? And, what about the evidence-based literature which suggests that many of the early phase I treatments may be unnecessary, at least for certain malocclusions and certain appliances; i.e., better treated at a later time.2-6

On further reflection of JoJo’s case, a contemplated question comes to mind. That is, “Why don’t all cases similar to JoJo’s return to the pre-existing state after the pacifier or habit is discontinued?” Could it be that the children with rather normal dental-facial features (normal soft and hard tissue) prior to habit use are in the best position for the malocclusion to be self-correcting? Conversely, would children who have facial and dental imbalances before the habit started, be less likely to have their malocclusions self-correct (at least fully correct)?

In addition, JoJo’s case stimulates the discussion of the never-ending debate of the question as to what comes first, the proverbial “chicken or egg.” This is regard to dental open bites and tongue thrusts. Parenthetically, this debate often ignores the possibility that both the open bite and tongue thrust developed and then ceased concomitantly.

Lastly, although case studies are not the best type of research, they can provide useful information. For instance, they can stimulate the formation of hypotheses that then provoke experimental research. The disadvantages of case studies are many. For one, with a sample size of “one,” there is not much that can be gleaned from an evidence-based perspective.

Conclusions

The results of clinical treatments, at times, may have little or nothing to do with the interventions that were rendered. Some outcomes in clinical practice and in research are best explained as natural or chance occurrences. It is advantageous for clinicians to contemplate the importance of bringing the knowledge of science, evidence-based medicine, and research to the patient care arena.

Delaying orthodontic treatment in younger children has been a topic for debate. For more on this topic, read “Lessons learned: a two-phase orthodontic treatment plan,” by Dr. Klifford Kapus here: https://orthopracticeus.com/lessons-learned-a-two-phase-orthodontic-treatment-plan/

- Leotti LA, Iyengar SS, Ochsner KN. Born to choose: the origins and value of the need for control. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010 Oct;14(10):457-463. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.08.001.

- Proffit WR. The timing of early treatment: an overview. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006 Apr;129(4 Suppl):S47-49. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.014. PMID: 16644417.

- O’Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Appelbe P, Davies L, Connolly I, Mitchell L, Littlewood S, Mandall N, Lewis D, Sandler J, Hammond M, Chadwick S, O’Neill J, McDade C, Oskouei M, Thiruvenkatachari B, Read M, Robinson S, Birnie D, Murray A, Shaw I, Harradine N, Worthington H. Early treatment for Class II Division 1 malocclusion with the Twin-block appliance: a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009 May;135(5):573-579. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.042.

- Rinchuse DJ, Miles P. Chapter 2. Early intervention: The evidence for and against. 7-16. In: PS Miles, DJ Rinchuse, DJ Rinchuse. eds. Evidence-Based Clinical Orthodontics. Quintessence Publishing: Chicago;2012:7-16.

- Schneider-Moser UEM, Moser L. Very early orthodontic treatment: when, why and how? Dental Press J Orthod. 2022 Jun 10;27(2):e22spe2. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709. 27.2.e22spe2.

- Perillo L. Editorial: Early treatment: Where are we today? Sem Orthod. 2023;29(2): 117-118.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Dara L. Rinchuse, DMD, graduated from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine (DMD) in 2008 and Jacksonville University School of Orthodontics (Certificate) in 2010. She is in private orthodontic practice in Rostraver, Pennsylvania. She has authored several papers, including several in the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. She can be reached at dararinchuse13@gmail.com.

Dara L. Rinchuse, DMD, graduated from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine (DMD) in 2008 and Jacksonville University School of Orthodontics (Certificate) in 2010. She is in private orthodontic practice in Rostraver, Pennsylvania. She has authored several papers, including several in the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. She can be reached at dararinchuse13@gmail.com. Donald J. Rinchuse, DMD, MS, MDS, PhD, graduated from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine in 1974 with degrees in Dentistry (DMD) and Pharmacology/Physiology (MS). He received his certificate and MDS degree in orthodontics in 1976 and a PhD in Higher Education in 1985 from the University of Pittsburgh. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics. In addition, Dr. Rinchuse is on the editorial review board of many professional journals including the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. He has published over 150 articles, two books, several book chapters, and has made many presentations. He can be reached at rinchuse21@gmail.com.

Donald J. Rinchuse, DMD, MS, MDS, PhD, graduated from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine in 1974 with degrees in Dentistry (DMD) and Pharmacology/Physiology (MS). He received his certificate and MDS degree in orthodontics in 1976 and a PhD in Higher Education in 1985 from the University of Pittsburgh. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics. In addition, Dr. Rinchuse is on the editorial review board of many professional journals including the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. He has published over 150 articles, two books, several book chapters, and has made many presentations. He can be reached at rinchuse21@gmail.com.