CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to provide an overview of judicious use of antibiotics in the dental practice to avoid antimicrobial resistance.

Expected outcomes

Implant Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Observe some data regarding indications for appropriate use of antibiotics.

- Identify some ways to prevent transient bacteremia from dental procedures.

- Realize some published guidelines related to the prevention of infective endocarditis.

- Recognize antibiotic prophylaxis in regard to prosthetic joint Infections.

- Identify some pediatric considerations in antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, and Jessica Price continue their discussion of concepts surrounding antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry

Introduction

Use of antimicrobials in the field of dentistry is not limited to treating active dental infections. Many dentists prescribe antibiotics as a onetime dose prior to performing procedures. In fact, in the United States, general and specialty dentists are the third-highest prescribers of antibiotics in all outpatient settings.1 Moreover, looking at data from 2017 to 2019, it is estimated that somewhere between 30% to 85% of dental antibiotic prescriptions are “suboptimal or not indicated.”2-4 Appropriate use of antibiotics for prevention of infections surrounding dental procedures has received a lot of attention recently, which was illustrated by the American Dental Association (ADA) updating its antibiotic stewardship recommendations in the fall of 2020.5 It is well-known that antibiotics are one of the greatest medical advances that laid a foundation for an area of medicine, which has allowed once deadly infections to be readily treatable.6 However, excessive antibiotic use, even if it is just one dose, comes with consequences of side effects, antibiotic resistance, and superinfections like Clostridioides difficile.

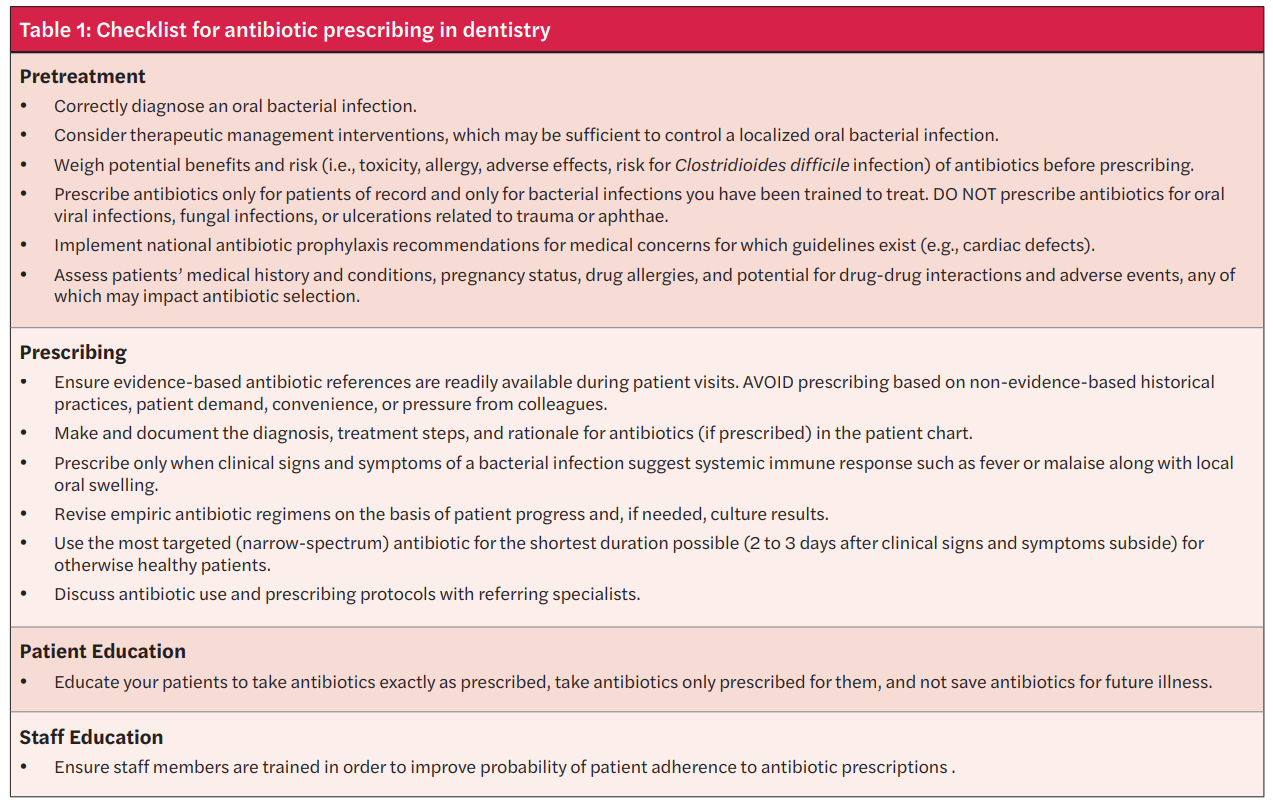

Being attentive to appropriate antimicrobial prescribing is vital in all fields of healthcare, including dentistry, which is not limited to treatment, but also applies to antimicrobial prophylaxis.7,8 To aid in considering the threats of overusing antibiotics, but also being able to recognize when antibiotics are warranted, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has constructed a Checklist for Antibiotic Prescribing in Dentistry (see Table 1). This checklist serves as an excellent supplement to concepts surrounding antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry that will be discussed in further detail.9

Prevention of transient bacteremia from dental procedures

There are antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations for two types of patients undergoing invasive dental procedures, which include those with heart conditions who may be at an increased risk of infective endocarditis and those with prosthetic joint(s) who may be predisposed to the development of a hematogenous infection at the site of the prosthetic(s). The oral cavity is colonized with numerous microorganisms that comprise between 300 to 600 species of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. The rationale for antibiotic prophylaxis is to reduce or eliminate transient or intermittent bacteremia (bacteria in the bloodstream) caused by invasive dental procedures that might result in more severe infections for these high-risk patients.10 Theoretically, patients with certain conditions and/or a compromised immune system might not be able to mount an immune response adequate to clear intermittent bacteremia originating from their oral flora. However, the exact risk is unknown as transient bacteremia from everyday activities (e.g., brushing teeth, chewing) might pose a higher risk for closed-spaced infections in these populations than transient bacteremia after a dental procedure in a patient without an active dental infection.11,13

Antibiotic prophylaxis: infective endocarditis

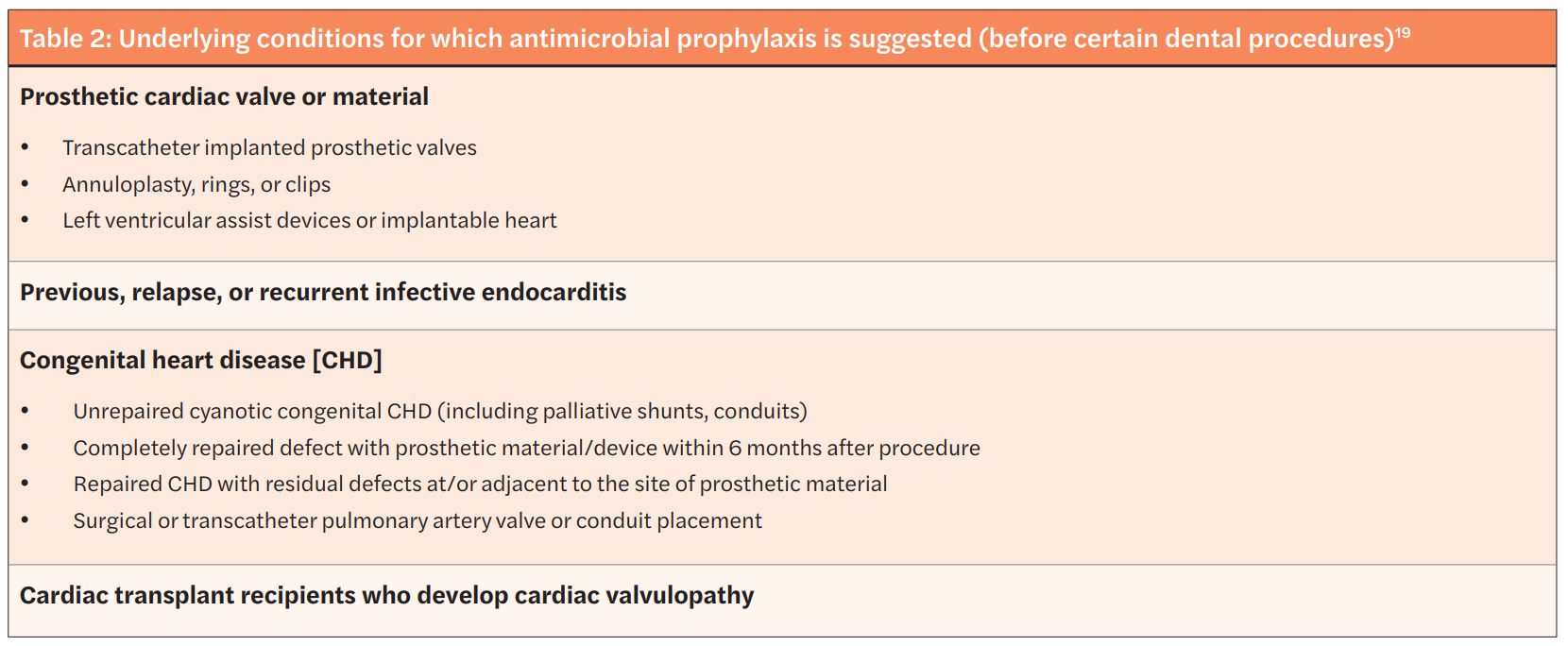

In 2008, the American Heart Association (AHA) published guidelines related to the prevention of infective endocarditis, which included guidance from the American Dental Association (ADA).13 The first iteration of the guidelines were supplemented with an updated scientific statement by the AHA in 2021.14,15 The scientific statement reaffirmed previous recommendations that prophylaxis is warranted in only a small subset of patients at highest risk of adverse outcomes. The recommendations consider the available evidence, weighing the benefits of preventing infective endocarditis with the risks, which include undue adverse effects as well as contribution to antimicrobial resistance. Moreover, these recommendations only apply to invasive dental procedures in which there is manipulation of the gingival tissue or periapical region of teeth, or perforation of the oral mucosa.16-18 The four broad categories of underlying conditions for which antimicrobial prophylaxis is advised are summarized in Table 2. The antibiotics suggested for use in those who are deemed to be at highest risk have empiric activity against the most common oral bacterial pathogens, most notably viridans group streptococci. The antibiotic regimen is chosen based on patients’ age, history of antibiotic allergy, and whether they can take oral medications (see Table 3). The antibiotic is given as a onetime by mouth dose 30 to 60 minutes prior to the invasive dental procedure; hence, prior to the dental appointment, patients would need to have a prescription written with enough time to have it filled and administered. If the prescription is inadvertently not taken by patients before the procedure, then it can be given up to 2 hours after the procedure.19

One notable change in the 2021 AHA recommendations is that clindamycin has been removed from the options for prophylaxis because it may cause more frequent and severe reactions than other antibiotics used for prophylaxis.19 Clindamycin used to be the recommended prophylactic agent for patients with severe penicillin allergies. However, clindamycin has a listed a black box warning for Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), which can be seen with onetime doses. The Minnesota Health Department found that patients were significantly more likely to have received a prescription for clindamycin in comparison to patients who received prescriptions from other non-dental providers. In this same study between the years of 2009 to 2015, it was found that 15% of patients with community-acquired CDI were treated by their dentist showing that a onetime prescription can produce undue downstream effects.20 The suggested alternatives for individuals unable to tolerate penicillin and β-lactam agents are azithromycin, clarithromycin, or doxycycline. If a patient has a non-IgE mediated allergy to penicillin or ampicillin, first- or second-generation cephalosporins can be chosen.19

Antibiotic prophylaxis: prosthetic joint Infections

In contrast with antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis, the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs concluded that “Evidence fails to demonstrate an association between dental procedures and prosthetic joint infections or any effectiveness for antibiotic prophylaxis.” Given this information in conjunction with the potential harm from antibiotic use, using antibiotics before dental procedures is not recommended to prevent prosthetic joint infections. Additional case control studies are needed to increase the level of certainty in the evidence to a level higher than moderate.21 Due to the paucity of available literature in this area, there may be individual scenarios when it is not apparent if antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated. In these cases, all patients, their risk of invasive infection due to oral pathogens after a dental procedure, as well as the risks and the benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis should be carefully weighed.21-26 However, the ADA guidelines cite that in cases where antibiotics are deemed necessary, it is most appropriate that the orthopedic surgeon recommend the appropriate antibiotic regimen and, when reasonable, write the prescription.

Pediatric considerations in antimicrobial prophylaxis

Pediatric dosing considerations for antimicrobial prophylaxis are also found in the AHA guidelines as seen in Table 3. Recommendations for pediatric patients are similar to adults with respect to empiric pathogen coverage, type of dental procedure warranting prophylaxis, and the use of a single oral prophylactic antibiotic dose. Clinicians should ensure the pediatric weight-based dose does not exceed a single adult dose.26 Pediatric patients are approached with less concrete guidance than adult patients, which has been described in separate documents. More discussion regarding pediatric patients with a compromised immune system who may be at an increased risk of complications of bacteremia are discussed in the Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry.16,27 In the Best Practice Report provided by the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs, it is mentioned that there is a lack of data to fully support antimicrobial prophylaxis as well which high-risk patients should be considered for antimicrobial prophylaxis. Several additional conditions could also warrant prophylaxis for pediatric patients, including the following:

- immunosuppression secondary to human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV)

- severe combined immunodeficiency (SCIDS)

- neutropenia

- cancer chemotherapy

- stem cell or solid organ transplantation

- history of head and neck radiotherapy

- autoimmune disease

- sickle cell anemia or other asplenia

- chronic high dose steroid use

- uncontrolled diabetes

- bisphosphonate therapy

- hemodialysis27

Additionally, if a patient undergoing an invasive dental procedure has a vascular shunt, a consultation with the child’s physician is warranted to guide the need for and selection of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Summary

It is not only imperative to be cautious with antibiotic overprescribing for the intended treatment of dental infections, but also equally important that careful consideration is taken prior to prescribing antibiotics for dental infection prophylaxis. Although prophylaxis is generally a onetime dose of antibiotics, there is still the potential for negative downstream effects of antimicrobial resistance and/or undue side effects. Table 1 provides a summary of tools that can be utilized to assist dental practitioners in curbing antimicrobial threats surrounding dental prophylaxis as well as dental infection treatment.

Read the start of the discussion on dental infections and antibiotic resistance in part 1 of the CE. Don’t forget to take the quiz! https://orthopracticeus.com/ce-articles/dental-infections-help-avoid-antimicrobial-resistance-part-1/

References

- Durkin MJ, Hsueh K, Haddy Y, et al. An evaluation of dental antibiotic prescribing practices in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(12):878-886.

- Gross AE, Hanna D, Rowan SA, et al. Successful implementation of an antibiotic stewardship program in an academic medical practice. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(3): 1-6.

- Suda KJ, Henschel H, Patel MA, et al. Use of antibiotic prophylaxis for tooth extractions, dental implants, and periodontal surgical procedures. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(1): 1-5.

- Loffler C, Bohmer F. The effect of interventions aiming to optimise the prescription of antibiotics in dental care: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017:12(11):1-23.

- American Dental Association. Oral health topics: Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures. American Dental Association website. Last updated January 5, 2022. Available at: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis Accessed October 27, 2022.

- Macfarlane G. Alexander Fleming: The Man and the Myth. Harvard University Press; 1984.

- Fluent MT, Jacobsen PL, Hicks LA. Considerations for responsible antibiotic use in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(8):683-686.

- Dana R, Azarpazhooh A, Laghapour N, Suda KJ, Okunseri C. Role of dentists in prescribing opioid analgesics and antibiotics: an overview. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(2):279-294.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Printable Checklist for Antibiotic Prescribing in Dentistry: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faqs/antibiotic-stewardship.html. Accessed October 27, 2022.

- American Dental Association. Oral health topics: Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures. American Dental Association website. Last updated January 5, 2022. Available at: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis Accessed October 27, 2022.

- Duval X, Leport C. Prophylaxis of infective endocarditis; current tendencies, continuing controversies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008; 8:225-232.

- Goff DA, Mangino JE, Glassman AH, et al. Review of guidelines for dental antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of endocarditis and prosthetic joint infections and need for dental stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(2):455-462.

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(suppl):3S-24S.

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2017;135(25): e1159-e1195.

- Wilson WR, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, et al. Prevention of Viridans Group Streptococcal Infective Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. 2021;143:e963-e978.

- Loyola-Rodriguez JP, Franco-Mrianda AF, Loyola-Leyva A, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis and bacterial resistance to antibiotics: A brief review. Spec Care Dentist. 2019;39:603-609.

- Goff DA, Mangino JE, Glassman AH, et al. Review of guidelines for dental antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of endocarditis and prosthetic joint infections and need for dental stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(2):455-462.

- Chen TT, Yeh YC, Chien KL, et al. Risk of infective endocarditis after dental treatments. 2018; 138(4):356-363.

- Thornhill MH, Dayer M, Lockhart PB, Prendergast B. Antibiotic prophylaxis of infective endocarditis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2017;19(2):9.

- Bye M, Whitten T, Holzbauer S. Antibiotic Prescribing for Dental Procedures in Community-Associated Clostridium difficile cases, Minnesota, 2009-2015. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(Suppl 1):S1.

- Sollecito TP, Abt E, Lockhart PB, et al. The use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for dental practitioners — a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(1):11-16 e8.

- Watters W 3rd, Rethman MP, Hanson NB. Prevention of Orthopaedic Implant Infection in Patients Undergoing Dental Procedures: J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(3): 180-189.

- Rethman MP, Watters W,3rd, Abt E, et al. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Dental Association clinical practice guideline on the prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):745-747.

- Meyer DM. Providing clarity on evidence-based prophylactic guidelines for prosthetic joint infections. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(1):3-5.

- American Dental Association-Appointed Members of the Expert Writing and Voting Panels Contributing to the Development of American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria. American Dental Association guidance for utilizing appropriate use criteria in the management of the care of patients with orthopedic implants undergoing dental procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(2):57-59.

- Quinn RH, Murray JN, Pezold R, Sevarino KS. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria for the Management of Patients with Orthopaedic Implants Undergoing Dental Procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(2):161-163.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients at risk of infection. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2019:416-421.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, BCPS, BCIDP, BCPPS, is an assistant professor of Pharmacy Practice at South College School of Pharmacy as well as an Antimicrobial Stewardship and Emergency Medicine Clinical Pharmacist practicing at a community hospital. She teaches infectious diseases as well a pediatric pharmacotherapy to both pharmacy and physician assistant students. Dr. Bruck received her bachelor of science in biology, followed by a Doctorate of Pharmacy degree, and then completed a postgraduate pharmacy residency program at William Beaumont Hospital in Troy, Michigan. Her research interests include antimicrobial stewardship, infectious diseases, as well as food allergy awareness. Dr. Bruck is Board-certified in pharmacotherapy, infectious diseases, and pediatrics.

Wiyanna K. Bruck, PharmD, BCPS, BCIDP, BCPPS, is an assistant professor of Pharmacy Practice at South College School of Pharmacy as well as an Antimicrobial Stewardship and Emergency Medicine Clinical Pharmacist practicing at a community hospital. She teaches infectious diseases as well a pediatric pharmacotherapy to both pharmacy and physician assistant students. Dr. Bruck received her bachelor of science in biology, followed by a Doctorate of Pharmacy degree, and then completed a postgraduate pharmacy residency program at William Beaumont Hospital in Troy, Michigan. Her research interests include antimicrobial stewardship, infectious diseases, as well as food allergy awareness. Dr. Bruck is Board-certified in pharmacotherapy, infectious diseases, and pediatrics. Jessica Price is a Doctor of Pharmacy candidate at South College School of Pharmacy in Knoxville, Tennessee. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Advertising and Public Relations, with minors in Business and English Writing from the University of Central Florida. Price completed her post-baccalaureate track in Biology at Florida International University and at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Jessica Price is a Doctor of Pharmacy candidate at South College School of Pharmacy in Knoxville, Tennessee. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Advertising and Public Relations, with minors in Business and English Writing from the University of Central Florida. Price completed her post-baccalaureate track in Biology at Florida International University and at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.