Drs. Richard Patterson, Daniel Rinchuse, Thomas Zullo, Lauren Sigler Busch, and Kay Youn, MFA, study the connection between braces and positive perceptions

Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate adults’ perception of adults who are wearing braces or clear aligners.

Materials and methods: A pilot cross-sectional study was conducted on eight photos with 20 lay adult raters, 10 male and 10 female, consecutively selected by investigator (RP) from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Four questions were asked regarding each randomly ordered photo:

1. How attractive is this person?

2. Does this person appear to be intelligent?

3. Does this person appear to be honest?

4. Does this person appear to be successful?

The outcome measure for each question was a 100 mm-long Visual Analog Scale.

Results: This study found no significant difference in raters’ opinions regardless of appliances worn when it comes to their perceived honesty. There was a statistically significant difference when adult raters judged an adult target with and without appliances as well as between different appliances in relation to attractiveness, intelligence, and successfulness.

Conclusions: In regards to attractiveness and intelligence, adults wearing clear aligners were rated as having higher attractiveness and intelligence than adults wearing metal braces. Male adult raters’ did not find any difference among the four target models in respect to successfulness; however, female adult raters rated models who wore clear aligner appliances as being more successful than models wearing metal braces. Conversely, the control female and male adult target photos received higher scores for all four questions when compared to adults wearing any form of orthodontic appliances, including clear aligners.

Introduction

There is a close relationship between physical appearance and attractiveness, with the face possibly being the most important part of the body in regards to attractiveness and interpersonal relationships.1-11 Attractive people are regarded as more friendly, intelligent, interesting, and more social, and are assumed to have more positive personalities overall.8-10 Because the mouth and teeth are essential elements in facial esthetic evaluations, orthodontists can play a large role in affecting how an adult is viewed by his/her peers.10 With this concept in mind, one could say that an individual’s perception of another will be somewhat based on his/her view of irregularities in the mouth or teeth. Nanda, et al., supported this belief by showing that irregularities in position of teeth and jaws can disrupt social interaction, interpersonal relationships, and mental well-being, and may lead to feelings of inferiority.11

For years, clinicians have been trying to understand what motivates patients to undergo orthodontic treatment. Research has investigated whether patients are motivated by improved function or more likely the desire to improve dental esthetics or the combination of function and esthetics.12 Studies have suggested that psychological and social gains from orthodontic treatment are more important than gains in oral health.12 The majority of studies involving esthetic perception and orthodontics have been performed using non-adult patients as the subjects in the evaluation of attractiveness, symmetry, and appearance of teeth. A systematic review from Samsonyanova, et al.,12 postulated that perhaps the reason is that most orthodontic patients are children and adolescents. Information regarding adult perceptions and esthetic perception is lacking because most perception studies use raters and target models that are children and adolescents.

The aim in this study is to evaluate how different types of orthodontic appliances on adults influence other adults’ perceptions. The goal is to answer the question that most adults ask themselves prior to orthodontic treatment, “Will my peers view me differently during orthodontic treatment?” This study specifically addresses the short-term impact that wearing orthodontic appliances has on adults’ appearance according to their adult peers. The study will correlate adults’ views on attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, and successfulness in relation to the type of orthodontic appliance an adult wears. Information garnered from this study will potentially aid in orthodontic appliance selection for adults by having a better understanding of how adults perceive other adults in orthodontic appliances.

Materials and methods

Selection of target persons

Prior to data collection, the project was approved by the Seton Hill University IRB in Greensburg, Pennsylvania. After IRB approval, three male and three female target patients were selected from Shutterstock.com (New York, New York), an online two-sided marketplace for creative professionals to license photos. Shutterstock.com allows models to promote their image for license to professionals who need stock model photos. Each model has given written consent to use their image for creative purposes as long as the manipulation is not explicit in nature. Models have been categorized by Shutterstock.com to allow for a refined search based on gender and attractiveness. Pools of models were selected using keyword average and then keyword male/female smiling. Inclusion criteria for models were adult Caucasian subjects over the age of 21 with relatively symmetric facial features. Exclusion criteria for models were any moderate to severe dental malocclusion, skeletal asymmetry, or excessive makeup/hair color or hairstyles that would be distracting to the rater. Potential target subjects with any other distracting features, including, but not limited to, inter-incisor diastema, maxillary and mandibular crowding, skeletal and profile anomalies, and anterior open bites that would deviate from a non-ideal smile, were also excluded.13,15,16

Each target model was photographed smiling from a frontal facial view “social view” with a similar relative focal size and background. Photos were 5 x 6 inch, printed in color photo paper and mounted on a green background. After completing a faculty rater consent form — seven clinical faculty from Seton Hill Center for Orthodontics, six male and one female faculty, all Caucasian in race with ages ranging from 45-65 years, with 20-plus years of experience — each screened and rated the six model photos. The models were rated on attractiveness based on a Likert scale of 1-7 (1 – signifying least attractive and a 7 – signifying most attractive). One female and one male model photo were selected based on receiving a mean score closest to average, between 3 and 5. By selecting average-looking models, the variable of attractiveness was effectively neutralized. Faces of average attractiveness were also used to prevent bottom and ceiling rating effects.15 Prior research showed that a person’s attractiveness has a significant effect on others’ perceptions of that person.13

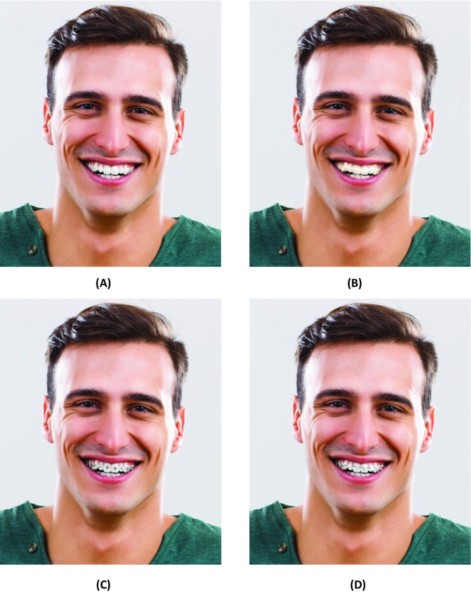

Manipulation of target person photos

The selected average level attractive models had his/her photo manipulated into four photos by the same expert operator (K.Y. Professor of Graphic Design, Seton Hill University and Creative Director/CEO of Youn Graphic and Interactive Design LLC) using Adobe Photoshop® (CS6; Adobe Systems, San Jose, California). Each model had his/her image manipulated to show the following: one photo with metal braces, one photo with ceramic braces, one photo with clear aligners, and the final photo with no ortho-dontic appliance. Manipulations were only performed on the models’ teeth so that the other facial characteristics were controlled. The photo manipulations produced eight frontal facial photos, four male and four female, which were rated in the study.

Raters

The eight photos were judged by 20 lay adult raters, 10 male and 10 female, consecutively selected by the principal investigator (RP) from Renaissance Church in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, new members group, and rated for attractiveness and three personality traits: intelligence, honesty, success. The 20 raters (10 female/10 male) in the study were Caucasian in race and were age range of 21 to 65. Laypersons were used because they are the “primary consumers of orthodontic treatment” according to McLeod, et al.14, and raters who have dental experience could have pre-existing bias toward orthodontic appliances. The raters were asked to review and sign a rater consent form prior to taking part in the study. They were given a script that briefly explains the study’s purpose but still kept them blind to the actual intent of the study. After signing voluntary consent forms, the raters received an 8.5″ x 11″ booklet that contained the eight 5″ x 6″ frontal facial photos, which were randomly assorted, each having a four-item questionnaire. The cover page of the booklet instructed the evaluators to answer the four questions after viewing each photo using a 100 mm visual analog scale. The cover page informed raters to notify the administrator if they knew or have had contact with either of the models. As expected, none of the raters had contact with either of the Shutterstock.com models.

Figure 1: Female target person. A. Control. B. Clear aligner. C. Metal brackets. D. Ceramic brackets

Figure 2: Male target person. A. Control. B. Clear aligner. C. Metal brackets. D. Ceramic brackets

Outcome measures

The images were accompanied with the following questions:

1. How attractive is this person?

2. Does this person appear to be intelligent?

3. Does this person appear to be honest?

4. Does this person appear to be successful?

Each question was presented along with a Visual Analog Scale from zero to 100 mm. This scale was a sliding scale, marked zero signifying complete disagreement, 50 for neutral, and 100 signifying complete agreement.9 The VAS, which is a reliable and commonly used scoring method in health research to generate parametric data,15 was used to correlate the eight independent variables to the four dependent variables. Each rater received a photo packet with randomly ordered target model photos to help with inter-rater reliability. This project methodology has been used previously for use in perception ratings because of its simplicity and rapidity.16 Because four questions were asked regarding each photo, and because there are eight photos, the questionnaire consisted of 32 questions. Upon receipt of the finished booklet the administrator (RP) marked whether the rater was male or female. After completion of the rater portion of the study, a debriefing session was offered to all raters discussing the intent of the research project.

Data compilation and statistical analysis

In this study the independent variables (intervention, exposure) were the target persons’ gender, the raters’ gender, and orthodontic appliance: metal braces on models’ teeth, ceramic braces on models’ teeth, clear aligners on models’ teeth, and control (no appliances). The dependent variables (outcome measures) were facial attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, and success as measured by the visual analog scale scores by the raters. The data was analyzed as a 2 x 2 x 4 MANOVA for two levels of rater gender, two levels of target photo gender, and four levels of modification. Because the only manipulation is the presence of a different type of appliance on the model photo, one could infer that any statistically significant difference from the control would show a difference in perception about that appliance versus the control. The scores for each question based on the corresponding model photo were compiled. The data was analyzed to see if this group of adults, at this given “slice of time,” showed a statistically significant difference in visual analog scale scores between a certain type of orthodontic appliance compared to the control photo with no orthodontic appliances, in regards to attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, or success. The data helped show which independent variable has a more positive or negative effect on each question’s VAS score by evaluators in relation to the control photo. The statistical analysis also allowed the researchers to evaluate any statistical significance between the rater’s gender and the model’s gender.

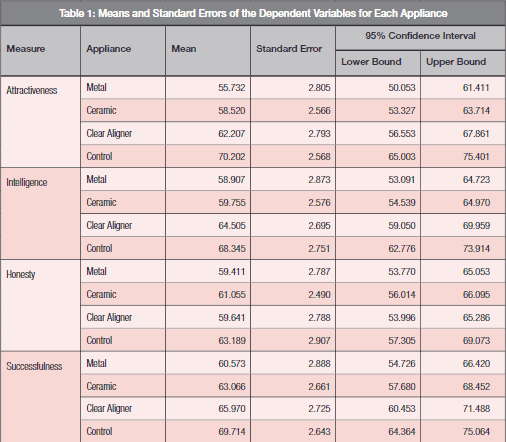

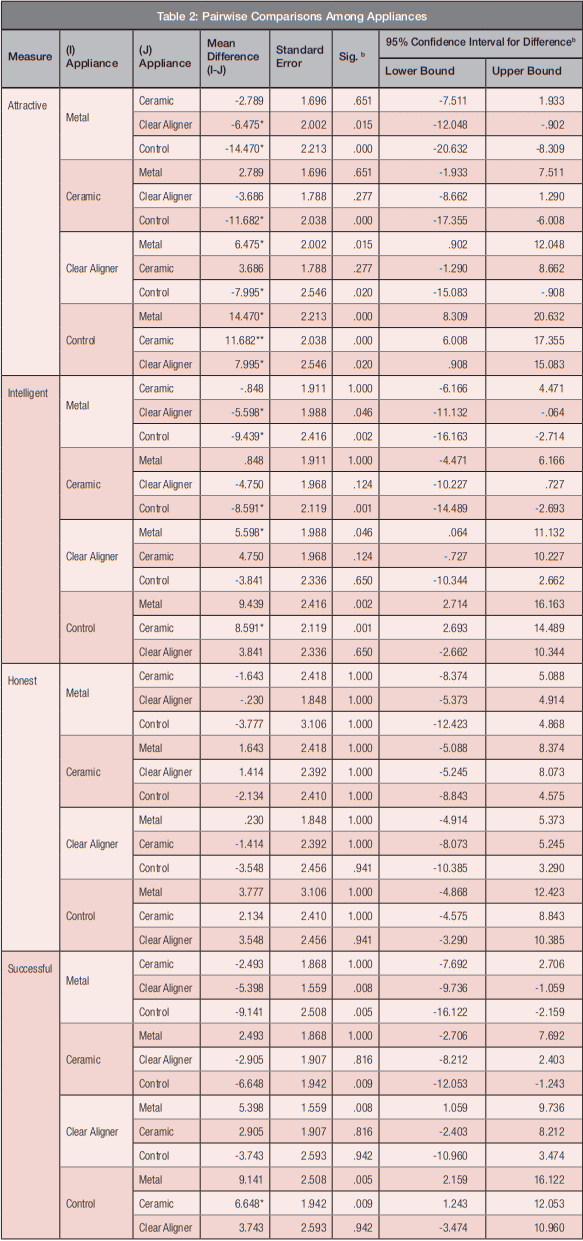

Based on estimaged marginal means. * The mean difference is significant at the .05 level. b Adjustment for multiple comparisons: Bonferroni.SPSS software (version 24.0; Armonk, New York) was used to calculate a MANOVA for two levels of rater gender (male/female), two levels of target photo gender (male/female), and four levels of modification (metal braces, ceramic braces, clear aligners, no appliance-control). Pairwise Comparisons (Bonferroni) (Tables 1 and 2) were performed to show the differences between the four appliance materials in relationship to attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, and successfulness in conjunction with the raters’ gender and target models’ gender. All data maintained a Type I alpha risk of .05 and a power of 80%.

* The mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

* The mean difference is significant at the .05 level. b Adjustment for multiple comparisons: Bonferroni.

Results

A total of 20 (10 male/10 female) raters successfully completed the VAS evaluation of four dependent variables of attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, and successfulness based on eight independent variables made up of six appliance manipulated target model photos (3 male/3 female) as well as a female and male control photo. Multivariate tests resulted in the following:

- There were no significant differences between male and female raters (F = 0.853, p = 0.503), male and female target models (F = 1.646, p = 0.185), or the interaction between raters gender and target models gender (F = 0.489, p = 0.743) for the set of four dependent variables (attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, and successfulness)

- There were statistically significant differences among the levels of modification (F = 4.701, p < 0.0004) for the set of four dependent variables (attractiveness, intelligence, honesty, and successfulness). Significant differences were found for attractiveness (F = 18.465, p < 0.0004), intelligence (F=8.52, p < 0.0004), and successfulness (F = 7.045, p < 0.0004). There were no significant differences for the independent variables in relation to honesty.

- There is a moderate interaction effect (p = 0.046) between raters’ gender and target models’ photos for the set of four dependent variables. Univariate tests showed that only the variable successfulness exhibited a significant interaction (F = 3.093, p = 0.030).

Discussion

Results did show a statistically significant difference when male and female adult raters judged a female or male adult target model with and without appliances in relation to attractiveness, intelligence, and successfulness. In regards to attractiveness and intelligence, clear aligners were appreciably more preferred by male and female adults than metal appliances. Male adult raters did not find any difference among the four target models in respect to successfulness: however, female adult raters favored clear aligner appliances over metal appliances in relation to successfulness. There was no statistical significance between ceramic braces adult target models and clear aligner adult target models when rated by adults in relation to attractiveness, intelligence, and success. Similar to Pithon et al,17 this study suggested that there is no significant difference in raters’ opinions whether female or male adults when judging a female or male adult target model with or without appliances when it comes their honesty.

The findings of this study support the concept that the psychosocial impact of orthodontic appliances on adults’ perspectives is significant and may affect an adult’s decision to undergo orthodontic treatment. In regards to attractiveness and intelligence, clear aligners were preferred by male and female adults over metal appliances. Conversely, the control female and male target photos were preferred the most overall in relation to attractiveness, intelligence, and successfulness. Based on these results, orthodontists may assume that adults who are seeking ortho-dontic treatment may have a more negative outlook on metal orthodontic appliances and are more likely to favor clear aligner treatment or no treatment to metal appliance treatment. Second, female raters deemed adult target models with clear aligners as more successful than metal braces target models. Male raters’ did not find any differences among the target models for the dependent variable of successfulness. (Tables 3 and 4) This supports the idea that female adults are more influenced by orthodontic appliances in relation to an adult’s success. This research suggests that adult females seeking treatment are more likely to request clear aligner appliance treatment over metal bracket appliance treatment based on the overall results of this research. This research shows adults do perceive their peers as less or more attractive, intelligent, and successful based on what type of orthodontic appliance they are wearing. A recent study by Pithon, et al.,17 found that adults do perceive other adults differently in regards to attractiveness and intelligence based on their “social smile.”

Limitations of this study are that it is observational, cross-sectional, and contain 20 adult raters, and therefore, it is limited in scope.

Conclusions

- In regards to adults rating other adults in orthodontic appliances, there was a statistical significance between ortho-dontic appliance types as it relates to attractiveness, intelligence, and successfulness.

- Clear aligner adult target models rated higher than metal bracket appliance adult models in relation to attractiveness and intelligence.

- Female adult raters’ favored clear aligner adult target models over metal bracket adult models in relation to successfulness. Male adult raters did not find any difference among the four target models in respect to successfulness.

- Control adult target models without appliances were statistically preferred over metal, ceramic, and clear aligner adult target models in relation to attractiveness, intelligence, and successfulness.

- Henson ST, Lindauer SJ, Gardner WG, Shroff B, Tufekci E, Best AM. Influence of dental esthetics on social perceptions of adolescents judged by peers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;40(3):389-395.

- Bale C, Archer J. Self-perceived attractiveness, romantic desirability and self-esteem: a mating sociometer perspective. Evol Psychol. 2013;11(1):68-84.

- Momentemurro B, Gillen MM. Wrinkles and sagging flesh: exploring transformation in women’s sexual body image. J Women Aging. 2013;25(1):3-23.

- Seidman G, Miller OS. Effects of gender and physical attractiveness on visual attention to Facebook profiles. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16 (1):20-24.

- Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C. Physical appearance as a measure of social ranking: the role of a new scale to understand the relationship between weight and dieting. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2013;20(1):55-66.

- Meyer-Mercotty P, Stellzig-Elsenhauer A. Dentofacial self-perception of adults with unilateral cleft lip and palate. J Orofac Orthop. 2009;70(3):24-236.

- Tatarunaite E, Playle R, Hood K, Shaw W, Richmond S. Facial attractiveness: a longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127(6):676-682.

- Honn M, Goz G. The ideal of facial beauty: a review. J Orofac Orthop. 2007;68(1):6-16.

- Tung AW, Kiyak HA. Psychological influences on the timing of orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;113(1):29-39.

- Helm S, Kreiborg S, Solow B. Psychosocial implications of malocclusion: a 15-year follow-up study in 30-year-old Danes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1985; 87(2):110-118.

- Nanda RS, Ghosh J. Facial soft tissue harmony and growth in orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod. 1995;1(2):67-81.

- Samsonyanova L, Zdenek B. A systematic review of Individual motivational factors in orthodontic treatment: facial attractiveness as the main motivational factor in orthodontic treatment. Int J Dent. 2014:2014:1-7.

- Olsen JA, Inglehart MR. Malocclusions and perceptions of attractiveness, intelligence, and personality, and behavioral intentions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140(5):669-679.

- McLeod C, Wiltshire W, Fields HW, Hechter F, Rody W Jr, Christensen J. Esthetics and smile characteristics evaluated by laypersons. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(2):198-205.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kokich VG, Kiyak HA. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(2):141-151.

- Howells DJ, Shaw WC. The validity and reliability of ratings of dental and facial attractiveness for epidemiologic use. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1985;88(5):402-408.

- Pithon MM, Naschimento CC, Barbosa GC, Coqueiro Rda S. Do dental esthetics have any influence on finding a job? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146(4):423-429.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores