Editor’s intro: Aveolar-focused orthodontics emphasizes the importance of root position for long-term case stability. Read Dr. Jeffrey Miller’s article to find out how CBCT facilitates this process.

Dr. Jeffrey Miller discusses the importance of considering the position of the roots within the alveolar housing

After 34 years of orthodontic practice, I have seen and participated in my share of “fads.” I remember getting so excited about using functional appliances only to later find out the mechanism of correction was not due to increased skeletal growth. In today’s highly competitive orthodontic arena and with the pressure to stay current on new and evolving technologies, orthodontic specialists often feel obligated to implement new trends into their practices before they are fully comfortable, resulting in decreased focus on areas that could be very helpful to patients’ treatment. For example, long-term case stability is not even a part of the conversation among some orthodontic Facebook groups.

I still believe that orthodontists provide a service that requires specialty training. However, for some types of patients, the rationale for keeping orthodontic treatment in the specialty arena has been vague at best. Consider a Class I patient with 3 mm-4 mm of dental crowding in each arch. Can you explain what an orthodontist is going to do differently than the “Do It Yourself Aligner Shop” around the corner for this case? Unfortunately, orthodontics for some has been reduced to the alignment of only the clinical crowns, forgetting about the roots, supporting bone, and long-term stability. One of the major differentiators is how the roots are positioned within the supporting bone. A successful orthodontic result must consider the position of the roots within the alveolar housing.

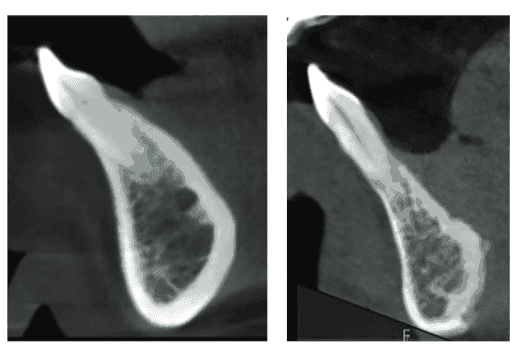

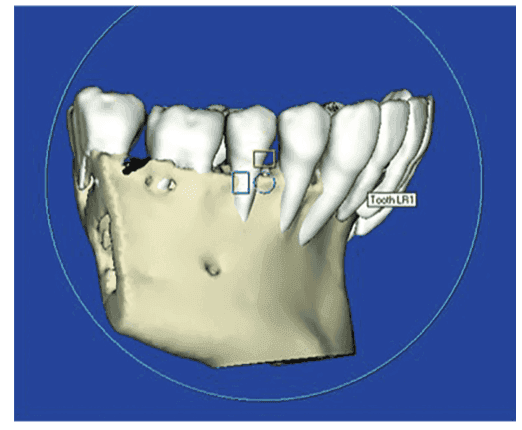

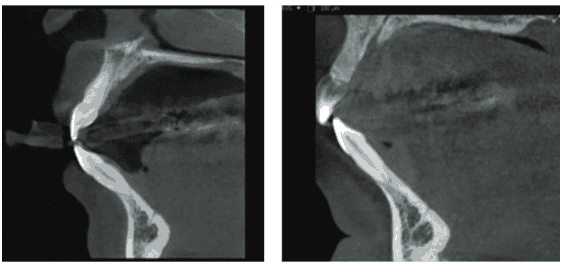

Figure 1 shows lower incisors from two different patients with similar malocclusions. Alveolar Focused Orthodontics (AFO) asks the following question: “Should the anatomy of the alveolar housing be a consideration in our orthodontic treatment strategy?” Obviously, the patient on the left has a significantly more robust alveolar housing than the patient on the right. If you consider the alveolar housing anatomy, and believe the best position for the root should be centered within the housing, then you would conclude that the patient on the right would require more precise tooth movement because of the limited housing. So, how do we get this information? Answer: CBCT.

Without CBCT, it would be impossible to determine the limitations of orthodontic tooth movement.

It is also becoming clearer via CBCT post-active orthodontic treatment studies that the alveolar housing does not modify significantly regardless of the bracket/wire system used. Although there is some controversy regarding the accuracy of CBCT in its ability to measure very thin bone, the quality of these images has increased over the past several years, making root dehiscence images more reliable. I believe that it is the ability to view individual teeth and their supporting bone that will move orthodontics away from the “clinical crown jockeys” and back to a specialty discipline of dentistry.

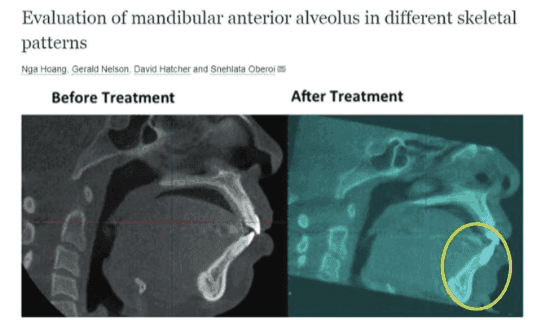

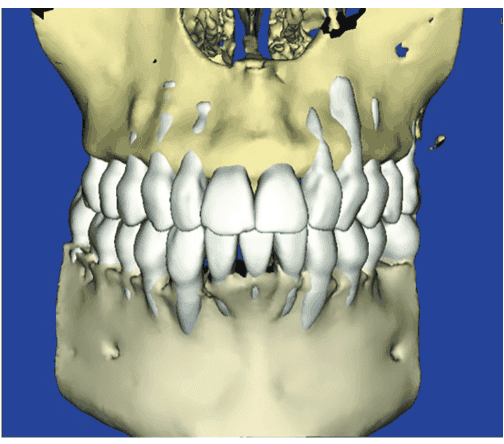

In a 2016 article by Drs. Hoang, Nelson, Hatcher, and Oberoi titled, “Evaluation of mandibular anterior alveolus in different skeletal patterns,”1 the authors found that high-angle patients seem to have the thinnest buccal lingual alveolar housing width, therefore limiting the amount of orthodontic expansion or constriction. Notice how the lower incisor has been pushed out of the alveolar housing after orthodontic treatment in Figure 2.

In the following case examples, I hope to explain why it is “mission critical” to consider the anatomy of the alveolar housing when providing orthodontic treatment.

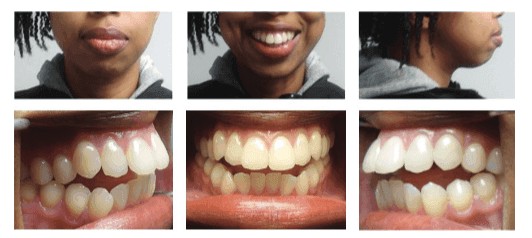

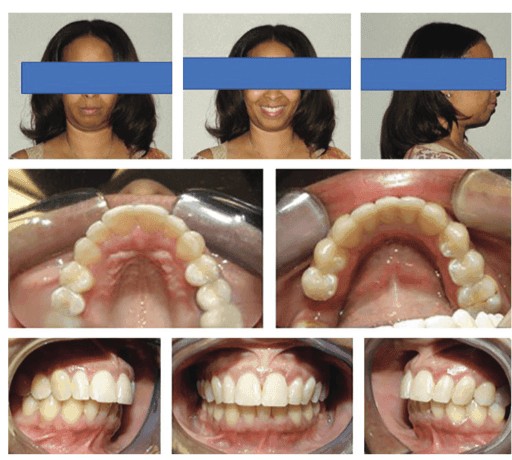

Let’s take a look at this 19-year-old female patient (Figure 3) with the following conditions:

- Poor lip competency

- Hyperdivergent skeletal pattern

- Skeletal open bite

- Slightly gummy smile

- Class I dental relationship

- Class II skeletal relationship

- Retrognathic mandible

- Bimaxillary Protrusion

- Slight tongue thrust

- Slight crowding in both arches

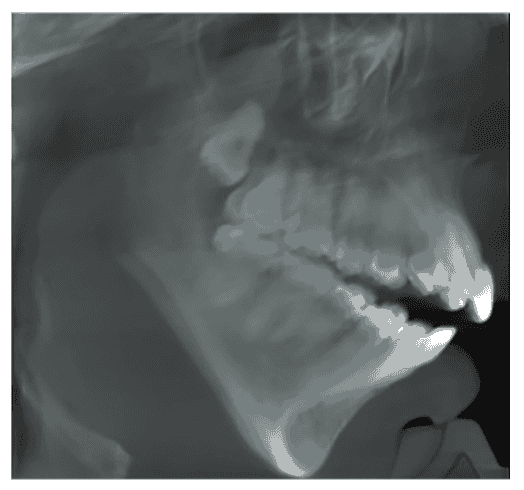

Based on a cephalometric analysis (Figure 4), an orthodontist would likely suggest one of the following treatment approaches:

- Extract lower first bicuspids, interproximal reduction of upper anterior teeth, and orthognathic surgery

- Extract all first bicuspids, intrude the molars (in an effort to close bite)

- Non-extraction treatment with inter-proximal reduction of both upper and lower anterior teeth, molar intrusion

- Non-extraction with upper and lower interproximal reduction and orthognathic surgery

Of course, no treatment also is always an option.

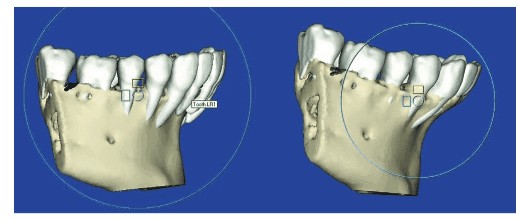

I would suggest that, based on a cephalometric analysis, the ideal treatment approach would be treatment number 1 followed by 2. However, if you were to consider the size and shape of the alveolar housing via CBCT, the treatment decision could change. Figure 5 shows this same patient with a clearer view of the central incisors and the supporting alveolar housing.

Notice the extremely thin alveolar housing associated with the lower central incisors. Extraction and retraction may not be in this patient’s best interest since dehiscence would likely result. Therefore, based on the CBCT review, plan number 4 followed by 3 maybe a better treatment approach.

Keep in mind that it is nearly impossible to assess the alveolar housing anatomy with traditional two-dimesional images (pano-ramic and cephalometric radiographs).

Orthodontic retreatments offer additional challenges due to “more” limiting size of the alveolar housings and the more advanced age of this patient population. Figure 6 demonstrates what appears to be a straightforward retreatment case. CBCT images (Figure 7) of this same patient tell a different story regarding the complexity of orthodontically repositioning this patient’s lower incisor.

Figure 7A shows two different patients, both showing the lower incisor dehisced through the buccal cortical plate. The patient on the left still has a fairly robust alveolar housing, which could reaccept the lower incisor root. Figure 7B shows this patient before and after root recapture (Incognito™ lingual appliance, 3M). The patient on the right (Figure 7A) is not as fortunate; the alveolar housing has resorbed, making root recapture very difficult without surgical intervention to augment the alveolar width.

I find it helpful to simulate multiple treatment options to determine which plan results in the best tooth/root/alveolus relationship. For example, Figure 8 shows an adult female patient with a Class I dental occlusion and a Class II skeletal relationship. Obviously, there are dental compensations of the lower incisors to accommodate the Class II skeletal pattern (lower incisors flared, pre-orthodontic treatment).

- The minimal width of the alveolar housing

- The procumbence of both the lower incisor and the alveolar housing that supports it

Achieving average clinical crown torque for these lower incisors would dictate uprighting of the roots (Figure 10). This “average” clinical crown torque would not comport with the underlying bone anatomy, therefore possibly orthodontically dehiscing the incisor roots through the cortical plate as seen in the SureSmile® treatment simulation in Figure 11.

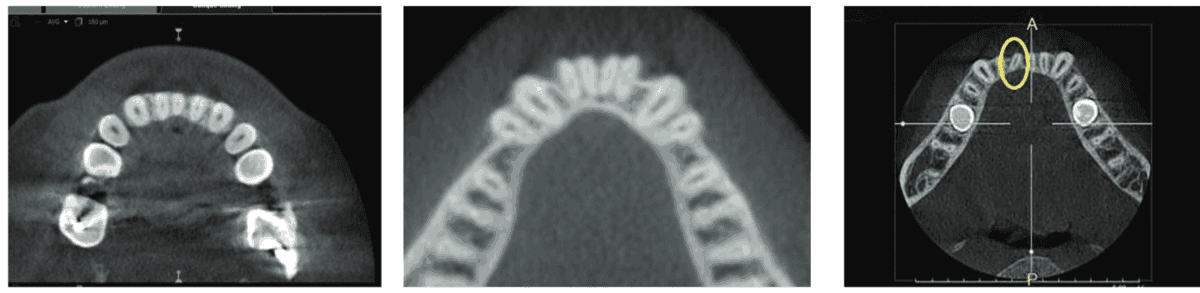

Using SureSmile software, different treatment approaches can be simulated. This simulation is based on the pretreatment CBCT (Figure 12). SureSmile creates a three-dimensional reconstruction that can be manipulated to simulate different treatment approaches. Figure 13 shows the simulation with a lower incisor extraction and upper interproximal reduction (cuspid to cuspid). Although the bone modeling is accurate within 0.20 mm, it shows the cortical plates as “static boundaries.” Because the changes to the shape and size of the alveolar housing are minimal when considering orthodontic tooth movement, the simulations should not be taken as the holy grail but rather as a general indicator for the root/alveolar housing relationship. Figure 14 shows two different treatment simulations for the same patient and the resulting effects to the lower incisor root/ alveolar housing relationship.

I believe a better treatment approach would be to attempt to keep the lower incisor roots in a position that maintains the root “reasonably” within the alveolar housing. Figure 15 shows 12-month post-active orthodontic treatment photos of this patient. Figure 16 shows the pretreatment and 12-month post-active orthodontic treatment sagittal slice (0.20 mm) of the lower central incisor. Notice that the resulting clinical crown torque is in alignment with the alveolar housing. Figure 17 compares the SureSmile treatment simulation with the actual post treatment CBCT 3D reconstruction.

Figure 18 compares two different post-active orthodontic treatment axial view slices (0.20 mm) contrasting Patient A (above case example) and Patient B’s post-active orthodontic axial views of the lower incisors. Notice that Patient A’s roots are properly within the alveolar housing where Patient B’s roots were orthodontically dehisced through the facial cortical plate (CBCT taken 3 years post-active orthodontic treatment).

I do not pretend to have all the answers. We are largely still figuring out the significance of these images. For example, Figure 19 shows a rotated lower right central incisor. Proper alignment would create increased dehiscence on both the buccal and lingual since the alveolar housing is not wide enough to accept the properly aligned root. Is this an indication for pre-orthodontic alveolar augmentation? Do we take a chance and hope the dehiscence will not manifest in a gingival problem? I am optimistic that our esteemed profession will have the answers to these questions in the next decade.

In a 1972 study, “The Six Keys to Normal Occlusion,”2 Dr. Lawrence F. Andrews described the position of the teeth in patients with no history of orthodontic treatment and reasonably good alignment and occlusion. In other words, he described where Mother Nature places the teeth for folks who are fortunate enough not to need our services. As far as I know, there has never been a reasonable scientific contradiction to this 47-year-old study. Yet think about how many claims are made suggesting that there is a new and improved position for the clinical crowns that provides superior orthodontic results without a single shred of scientific support. It reminds me of the kid on the playground who likes to make up the rules as the game is played.

In conclusion, I believe, as orthodontic specialists, we need to become more mindful of the underlying bone anatomy. Unfortunately, the underlying bone anatomy cannot be properly visualized using panoramic and cephalometric radiographs. Cone beam computed tomography allows for the alveolar housing to play a more “appropriate” role in our orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Our specialty is at a pivotal point; we can continue with the non-evidence-based fads that are so recklessly promoted, or we can recognize the game-changing power of CBCT.

In this author’s humble opinion, CBCT is no longer an option; it is an obligation.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Miller extends his gratitude to Dr. Kelly Wray for her assistance in editing this article.

Viewing root position is just one advantage of CBCT imaging. Discover more about the benefits of 3D from Dr. Jay Burton in his CE, “Using 3D imaging in orthodontics.”

- Hoang N, Nelson G, Hatcher D, Oberoi S. Evaluation of mandibular anterior alveolus in different skeletal patterns. Prog Orthod. 2016;17(1):22.

- Andrews LF. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am J Orthod. 1972;62(3):296-309.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Jeffrey C. Miller, DDS, received a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology from Towson State University, and his dental degree from University of Maryland Dental School. He has a Certificate in Orthodontics from the State University of New York at SUNY Buffalo and is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics. He has been in private practice since 1984 and currently practices in the Baltimore, Maryland area. Please email Dr. Miller if you are interested in joining the Alveolar-Focused Orthodontic Facebook group,

Jeffrey C. Miller, DDS, received a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology from Towson State University, and his dental degree from University of Maryland Dental School. He has a Certificate in Orthodontics from the State University of New York at SUNY Buffalo and is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics. He has been in private practice since 1984 and currently practices in the Baltimore, Maryland area. Please email Dr. Miller if you are interested in joining the Alveolar-Focused Orthodontic Facebook group,