CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss the therapeutic or behavioral interventions that lead to a

preventive approach to sleep-disordered breathing.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify the main determinants of airway resistance.

- Realize the importance of airway size.

- Realize the resilience of the airway.

- Recognize the involvement of the velocity and turbulence of the airflow.

- Identify some possible changes in daytime breathing behaviors.

- Learn about some airway-related craniofacial dysfunctions.

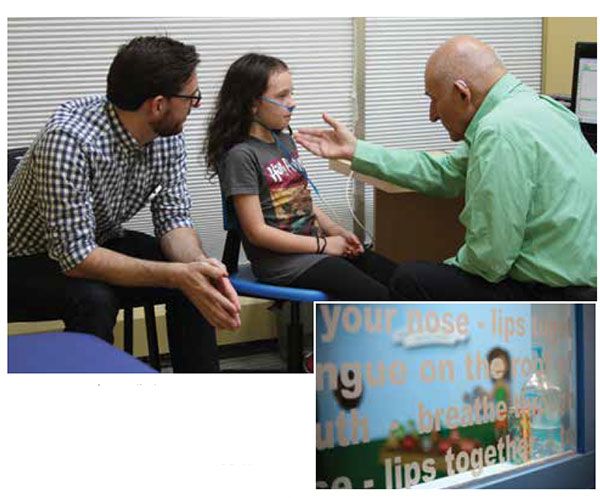

Dr. Barry D. Raphael discusses some ways to mitigate predisposing risk factors to airway resistance

Two cardiac surgeons are sitting at lunch discussing the comparative benefits of bypass surgery versus stents for maintaining coronary artery patency when a PCP sitting at the next table rudely interrupts, “Wouldn’t it be better to prevent the obstruction in the first place?”

Two sleep docs are sitting at another table discussing the comparative benefits of CPAP versus mandibular advancement devices when the same nosy-body again interrupts, “Wouldn’t it be better to prevent the obstruction in the first place?”

The analogy is apt and significant. No one would deny that many of the factors that lead up to a coronary can be addressed by either therapeutic or behavioral interventions and that, certainly, prevention is a far better choice. But there has been an absence of such discussion regarding occlusion of the airway. The purpose of this article is to stimulate such a discussion and to paint, with fairly broad strokes, a picture of what a preventive approach to sleep-disordered breathing would look like.

The etiology and predisposition to breathing disorders during sleep

It was once thought that obstructive sleep apnea was a disease of old, fat men. We have since learned that thin, athletic women can also fall victim to this problem. We have learned that while weight and age add to the susceptibility to obstructive sleep disorders, they are not the root causes. Difficulty breathing at night comes from resistance to airflow and there are many circumstances that can make breathing difficult. Efforts at pinpointing the source of resistance are important to determining proper remediation.

We have learned from flow physics and airway physiology that there are three main determinants of airway resistance:1

- Size of the airway

- Collapsibility of the airway

- Velocity and turbulence of the airflow

Delving into the physics of each is not the point of the article. Instead, the way that each of these factors can be addressed — well before the first apnea ever occurs with either therapeutic or behavioral interventions — will be the goal of this article. By defining opportunities to mitigate predisposing risk factors to airway resistance, we can begin to build a new paradigm in airway and sleep management. As such, the focus will be on prevention so that, just as we might prevent the heart attack, the end-stage disease of obstructive sleep apnea might never occur. From this discussion will emerge a new field of Airway Dentistry and Orthodontics that can define a possible future for the way orthodontics is practiced.

The size of the airway

Yes, losing weight and reducing fat deposits in the neck are important, but we also know that craniofacial morphology is a primary risk factor for breathing problems as well.2,3,4,5 Orthodontics has long been concerned with the growth and development of the face with regard to facial profile and the correction of skeletal and dental malocclusion, but has only recently considered its relevance to the formation of the naso-oropharyngeal airway.6 Anatomically, the maxilla (and the soft palate that hangs off the back of it) and the mandible (with the tongue attached to it) create the anterior boundaries of the airway. Studies have shown how retroposition of the bones relative to the face narrow the airway and create the risk for obstruction.7,8 This is true in both adults and children. Orthopedic treatments in children are now being explored to help enlarge — or at least prevent restriction of — the airway in a more natural and permanent way.9

Most of the focus in orthopedic research has been on palatal expansion, with the purpose of widening the nasal aperture and palate, with equivocal results.10,11 Additionally, studies show that bringing either or both jaws forward with advancement appliances or orthognathic surgery can be effective in opening the airway in the adult.12 We also know helping either jaw grow forward in the child may also be helpful.13 More recent work shows that changing maxillary growth in all three planes of space, including advancement, provide even more promising results.14

Playing off findings in the anthropology literature, the shape of the maxilla has changed dramatically in the modern human. This transformation is associated with a rapid change in the following environmental challenges, all of which have become rampant in today’s world:15

- dietary (high sugar and refined carbohydrate content)

- metabolic (autonomic and digestive stressors)

- cultural (early feeding and weaning habits)

- breathing (open mouth and low tongue postures)

- postural (forward head and slumped shoulders)

- sleep (artificial light and altered sleep cycles)

- inflammatory (a changing gut biome)

Given the rapidity of the environmental change, purely genetic variations must be ruled out.

Epigenetic variations of the bone’s shape, however, indicate that it is changing in width, yes, but also slumping downward and failing to fill out sagitally as well, a condition being called Craniofacial Dystrophy.15 This near universal midface deficiency (no matter the Angle classification of the teeth) has formed a bone with a collapsing palate with insufficient room for the teeth, and that often restricts the forward growth of the mandible hampering proper positioning of the tongue — all of which limit the eventual size of the airway.

Helping the jaws grow forward, not just wider, is the ultimate goal. Reversal of midface collapse presents numerous challenges to current orthodontic paradigms that often look to retract teeth and jaws distally, but it also empowers us as well. There has been a thread of thought throughout the historical orthodontic literature supporting the idea that a palate is not just congenitally narrow, but becomes narrow due to habits and practices that occur after conception.16 Altering these habits can begin to heal the dystrophy.

If the modern lifestyle can create these changes to the modern face so rapidly (in the past 300-400 years), then human ingenuity can reverse them as well. Originally separately stated by leaders of thought like George Crozat17, Edward Angle, and Alfred Rogers18 in the early part of the last century, modern philosophies of treatment, including Crozat, Advanced Lightwire Functionals, Postural Orthodontics, Biobloc Orthotropics, Cranial Osteopathy, and Myo-functional Orthodontics, all seek to reverse the conditions that lead to midface collapse. All these schools of thought have a common goal of reestablishing postural support of the growing maxilla by maintaining the resting tongue on the palate as a scaffold for the growing (and non-growing) bone.

The protocols that encourage forward growth of the jaws have all found some measure of success in reducing sleep-disordered breathing.19,20,21 Furthermore, treatments that restrict forward growth or reduce the size of space for the tongue have been shown to reduce airway size and, for purposes of breathing, should be avoided.22 More research in this area is needed, but common sense says that any technique that widens the airway space will be helpful in combating breathing problems.

Resilience of the airway

Even a fairly substantial airway can be closed off if the walls cannot withstand the turbulence created by the airflow within it. There are a number of points along the way from the nose to the lungs where soft tissue is apt to give way to the negative pressure. And there are a number of conditions that can decrease the resilience and increase the collapsibility of these tissues — all of which are reversible to some extent.

- Swelling of lymphoid tissue is perhaps the most commonly recognized problem.23 Tonsils and adenoids are currently thought of as the predominant risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing in children. The American Academy of Pediatrics has recently stated that surgical removal of lymphoid tissue can be considered a first line of treatment in obstructive sleep apnea.24 But one question that is rarely asked is, Why do lymphoid tissues get so swollen as to block the airway? While they are known to be more active in a young growing child, their enlargement, like the collapsed palate, is not a congenital given. Efforts to reduce the swelling can sometimes dramatically open the airway and may reduce the need for surgery.

Some of the methods used to reduce lymphoid swelling include:

- A transition from mouth breathing — which allows unfiltered air to irritate the tonsils — to nasal breathing — which filters and conditions the air before it gets to the lymph tissue — can reduce swelling within weeks;

- Improvements in body posture and muscular movement, as with regular exercise, can also help lymph tissue drain adequately;

- A transition from accessory muscle use to proper use of the diaphragm for breathing also helps lymphatic circulation;

- Nasal lavage to keep sinuses open and airway walls clean can help;

- Massage and bodywork can help lymphatic circulation;

- Acupuncture and homeopathic remedies that encourage drainage of lymph tissue throughout the body;

- The use of ozone and ozonated water injected into the swollen tissue has been shown to reduce lymph swelling;

- Short-term use of nasal steroids and decongestions as a good head-start are helpful.

Certainly, it’s better to try to shrink swollen lymph tissues as a preliminary approach. The frequent recurrences seen after surgical removal are probably linked to a failure to incorporate some of the above conservative measures post-surgically, especially continued oral breathing. This makes a conservative approach all the more important as a first line of defense as it has to be done even when the tissues are removed.

2. Poor muscle tone is also associated with blockage of the airway. Certainly the tongue falling back into the oral cavity at night is well recognized as a risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing. But well-toned extrinsic and intrinsic glossal muscles resist backward displacement. The use of myofunctional therapy, with specific exercises for creating better muscular balance of the pharyngeal musculature, has been shown to be helpful in reducing airway collapse at night and deserves more attention in this field.25 Even learning to play the Australian didgeridoo has been shown to be helpful in reducing pharyngeal collapse

at night.26

3. Chronic inflammation of pharyngeal tissues makes them less able to resist negative pressure due to loss of elasticity. The constant trauma to the tissues of the flapping of snoring only serves to irritate, elongate, and soften pharyngeal tissues and the soft palate. Chronic assault by stomach acid from gastric or laryngeal reflux is another source of inflammation that needs to be addressed. The cause of reflux itself can be addressed by changes in breathing mode (i.e., nasal breathing) and posture, too, thereby reducing reliance on protein pump inhibitors that have their own side effects. Finally, honing in on foods — some natural, some not — that instigate inflammation or a disturb the natural flora in the gut and supplanting them with healthier choices can change the condition of the airway as well as the rest of the body.

Velocity and turbulence of the airflow

Though the way air flows through the breathing space has been tested and studied, and recognition of air pressure changes within the pharynx and within the thoracic cavity has been given due consideration, little attention has been paid to the behaviors that actually create these negative pressure conditions. In fact, some theorize that it is not the nighttime breathing that creates the biggest problem, but the daytime habits of breathing that set up the circumstances for airway collapse at night.27

These conditions include habitual over-breathing in response to the many chronic stressors that we encounter each day. Our autonomic nervous system is constantly activated without a chance for recuperation, setting in motion a cascade of events that result in, among many other things, rapid shallow breathing with tidal volumes nearly three times what is necessary for efficient oxygenation — in other words: chronic hyperventilation.

It is said that over-breathing is just as dangerous to health as overeating. Chronic hyperventilation, especially with the large portal of an open mouth, shifts the balance between oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs and in the blood. Chronic hypocapnia is a common condition in mouth breathers and can result in reduced oxygenation of tissues (the Bohr effect) and increased smooth muscle spasm (think vessels and organs). The symptoms from these two phenomena alone are quite diverse, affecting the vasculature (hypertension, venous pooling); organs (enuresis, digestive issues); tubes (asthma, reflux, xerostomia); and tissue perfusion (neurocognitive deficits such as attention, memory and learning, anxiety, and muscle fatigue and spasm). And, oh yes, apnea.

Heavy breathing at night pulls air through the pharynx rapidly, creating increased turbulence and negative pressure. This can compromise an otherwise healthy system (e.g., snoring only when you get intoxicated). Combine that with small airway size and increased collapsibility, and you have the perfect internal storm — a hurricane in a box, if you will.

Some think that central sleep apnea is nothing more than the body’s respiratory mechanism taking a pause to restore proper carbon dioxide levels and maintain homeostasis. While this thinking seems to be in direct opposition to the commonly held view that sleep-disordered breathing is a problem of hypoventilation and hypercapnia, a change in daytime breathing mode — again, from oral to light nasal breathing — can alter nighttime distress almost immediately in some patients.28 In fact, the relationship between daytime breathing habits and nighttime distress is so strong, the syndrome should be called breathing-disordered sleep instead of sleep-disordered breathing.

Adopting new changes in daytime breathing behaviors should be the first line of defense in the treatment of breathing-disordered sleep. Simple breathing training includes:

- Nasal breathing primarily, even during activity if possible;

- Reduction of tidal volume by reducing breathing rate and depth;

- Use of the diaphragm for powering inspiration.

Biofeedback techniques are especially helpful in retraining daytime breathing. Once the body can accommodate to this new breathing mode, there is often no longer such a struggle at night. And at very least, modalities like CPAP and MADs can become more tolerable.

Airway-related craniofacial dysfunctions: a change in paradigm

Besides sleep apnea, there are a host of refractory conditions that dentistry has been struggling with that are now being looked upon as airway-related craniofacial dysfunctions (ACDs).

They include:

- Chronic naso-pharyngeal obstruction (physical or functional)29

- Tethered oral tissues (lip-tie and tongue-tie)30

- Open mouth rest posture (with the tongue off the palate)31

- Myofunctional disorders (swallowing, chewing, etc.)32

- Chronic hyperventilation and hypocapnia33

- Breathing-disordered sleep (OSA, UARS, snoring)34

- Bruxism, parafunctions, and dental deterioration35

- TMD and facial pain components36

- Cranial and postural issues37

- Craniofacial dystrophy with malocclusion38

Each topic deserves its own discussion, but putting them under the umbrella of airway dysfunctions seems to have answered a lot of challenging questions for practitioners in all disciplines. In fact, once you see the relationship, it’s hard to see how we ever thought otherwise.

Airway orthodontics: a change in protocol

Putting these concepts into practice will be the next great challenge of the 21st century for orthodontics. Developing the protocols that will engender an understanding of the need for behavior change in our patients and creating the settings in which to support these changes are what we need to begin to do now. There are five domains in which airway orthodontics must create innovative, and even disruptive (in the business sense), solutions:

- Assessment

Looking at how once unclear symptoms are related to the need to breathe and achieve homeostasis will allow us to catch a system that is headed off course much earlier than any other sleep screening currently does.

- Prevention

When should treatment begin? As soon as the habits that create poor facial growth are discovered. This may begin before birth, at birth, in infancy, or whenever any airway-related problem begins. Many ancient cultures were well aware to never let their young leave their lips apart at rest. Breastfeeding is best feeding since it creates mechanical stimulation of growing bones. Tongues must not be tethered. Children need to chew real food. Noses must be kept patent. And that is just the starting point.

- Mitigation

By the time a person gets to OSA, it may be too late to do much but treat symptoms. But whenever damage from bad habits has been discovered, all attempts to reverse this damage should be made, and certainly, nothing should be done that would worsen or even perpetuate the damage (e.g, reducing or maintaining inadequate tongue space).39

- Habit training

It’s not easy. I will never say it’s easy. Or quick. Or certain. But if nothing changes in a person’s actions, nothing will change in a person’s health. There are no pills, no shots, no surgeries, no compliance-free appliances, and no shortcuts. Breathe right. Eat right. Sleep right. Be right.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration

The need to collaborate can be seen as another obstacle for what is now a solo practice. No one practitioner can handle all the etiologies patients may bring with them. As the Chinese say, “One disease, a thousand treatments … one treatment, a thousand diseases.” Such is the lot when looking at the whole person. A specialist may be able to reduce a person into small segments with isolated diseases and treat just those. But to create wellness, a variety of approaches may be necessary, requiring input from a variety of practitioners. The health and wellness center of today may be the best mode of practicing airway orthodontics for the future. And, by the way, while corporations are gobbling up practices and practitioners, this may also be the way to maintain some autonomy in our profession. By returning to the concept of orthodontist as a physician of the face, we open a new realm of possibilities.

The orthodontic practice of the future will include, in either one place or many:

- The airway-aware orthodontist

- Health educator (who knows myo-functional therapy, breathing and postural training, nutrition, lactation for the very young, and maybe some bodywork)

- Sleep/ENT/pulmonologist/allergist MD

- Cranial osteopath or physical therapist who manages the craniofacial skeleton

- Other auxiliaries in child development and wellness care

In this practice, there will be ample time set aside for talking with the patient/parent, for collaborative treatment planning, and for follow-up care. The environment will be conducive to learning as well as therapy. And finally, it will be a place where patients can get preventive, holistic, and allopathic care.

The goals of airway orthodontics

Here it is, for young and old, in a nutshell:

- Breathe gently through the nose, using the diaphragm at all times.

- Keep the lips together when not talking or eating.

- Keep the tongue on the palate at rest.

- Swallow without using the facial or cervical muscles.

- Balance yourself well against gravity. (Sit and stand straight!)

- Eat to nourish (with foods your body appreciates).

- Sleep to rejuvenate.

The future of orthodontics

The current gold standard treatment — if gold is the appropriate color — for obstructive sleep apnea is to artificially pry open the airway at night with air, plastic, or scalpel. Perhaps someday we’ll have Swarovski-studded tracheostomy plugs for a more perfect (read: fashionable and quick) solution.

But if you look at the progression leading up to obstruction, there are many, many opportunities to intervene, to change the trajectory of the disease, and to increase the quality of life. By helping the airway to grow larger (size), keeping the airway physically fit (resilience), and optimizing the airway’s use (flow), the problem can be, at worst, delayed and, at best, avoided.

While opportunities to mitigate the progression of airway dysfunction from birth to sleep apnea are plentiful, there are three large challenges to overcome — all of which are common to medicine and dentistry:

- Preventive medicine lacks the urgency most people need to create the behavior changes that create optimal health. Symptomatic treatment engenders changes but only so long as the symptoms last. Education and understanding are the only way to get people to change. Look how much we changed once we understood how the tobacco industry was victimizing us. Perhaps the same will happen for sugar soon. And then for sleep.

- While reducing treatment to its most simplistic outcome (i.e., prying the airway open or Class I occlusion) makes good business sense, this reductionist practice — as well as reductionist research that supports it — distracts us from dealing with the bigger picture.40 We must pay equal attention to “holistic” aspects of the human, with all its variables and vagaries. While this approach may require a change in thinking, in our education, and in our practice, we have to pay attention to the child attached to the teeth as much as the teeth attached to the child.

- Results will necessarily be subject to a bell curve, as it is with any educational system. Though most orthodontists are trained to strive for “perfect,” we will have to learn to settle for, as does medicine, and live with “better” as a standard of care. One might even argue that the health of the airway takes precedence over the occlusal schema, or, heaven forbid, esthetics, should a choice have to be made. This is a real shift in priorities.

In recent years, the orthodontic profession has been arguing about the relative benefits of early orthodontic treatment asking, “Is the benefit worth the burden?”41 One could ask the same question about the effort needed to prevent heart disease. Yet, today, fitness centers and whole foods establishments are becoming mainstream in our society answering that question by popular demand. Perhaps in days soon to come, there will be similar outcry looking for better sleep and breathing as well.

Part 2 of Dr. Raphael’s article, “Airway orthodontics the new paradigm: part 2, addressing malocclusion and facial growth,” will be published in the July/August issue.

References

- Chandra RK, Patadia MO, Raviv J. Diagnosis of nasal airway obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2009;42(2): 207–225.

- Aihara K, Oga T, Harada Y, Chihara Y, Handa T, Tanizawa K, Watanabe K, Hitomi T, Tsuboi T, Mishima M, Chin K. Analysis of anatomical and functional determinants of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2012; Jun;16(2):473-481.

- Dempsey JA, Skatrud JB, Jacques AJ, Ewanowski SJ, Woodson BT, Hanson PR, Goodman B. Anatomic determinants of sleep-disordered breathing across the spectrum of clinical and nonclinical male subjects. Chest. 2002;122(3):840-851.

- Lowe AA, Santamaria JD, Fleetham JA, Price C. Facial morphology and obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1986;90(6): 484-491.

- Ikävalko T, Tuomilehto H, Pahkala R, Tompuri T, Laitinen T, Myllykangas R, Vierola A, Lindi V, Närhi M, Lakka TA. Craniofacial morphology but not excess body fat is associated with risk of having sleep-disordered breathing—The PANIC Study (a questionnaire-based inquiry in 6–8-year olds). Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(12):1747–1752.

- Carlyle TD, Chmura L, Damon P, Diers N, Paquette D, Quintero JC, Redmond WR, Thomas B. Orthodontic strategies for sleep apnea. Orthodontic Products. April/May 2014;21(3): 92-101. https://www.orthodonticproductsonline.com/2014/04/orthodontic-strategies-sleep-apnea/. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- Dempsey JA, Skatrud JB, Jacques AJ, Ewanowski SJ, Woodson BT, Hanson PR, Goodman B. Anatomic determinants of sleep-disordered breathing across the spectrum of clinical and nonclinical male subjects. Chest. 2002;122(3):840-851.

- Katyal V, Pamula Y, Martin AJ, Daynes CN, Kennedy JD, Sampson WJ. Craniofacial and upper airway morphology in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;Jan;143(1):20-30.

- Singh GD, Garcia-Motta AV, Hang WM. Evaluation of the posterior airway space following Biobloc therapy: geometric morphometrics. Cranio. 2007;25(2): 84-89.

- Rose E, Schessl J. Orthodontic procedures in the treatment of OSA in children, J Orofac Orthop. 2006,67(1):58-67.

- Ruoff CM, Guilleminault C. Orthodontics and sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(2)2:271-273.

- Holty JE, Guilleminault C. Maxillomandibular advancement for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(5):287–297.

- Kaygisiz E, Tuncer BB, Yüksel S, Tuncer C, Yildiz C. Effects of maxillary protraction and fixed appliance therapy on the pharyngeal airway. Angle Orthod. 2009;79(4):660-667.

- Singh GD, Garcia-Motta AV, Hang WM. Evaluation of the posterior airway space following Biobloc therapy: geometric morphometrics. Cranio. 2007;25(2): 84-89.

- Boyd, K. Darwinian Dentistry: an evolutionary perspective on the etiology of malocclusion, part 1. Journal of the American Orthodontic Society. Nov/Dec 2011: 34-39.

- Mew, M. Craniofacial dystrophy: a possible syndrome? Br Dent J. 2014;216(10):555-558.

- Rogers, AP. Stimulating arch development by the exercise of the masseter-temporal group of muscles. Am J. Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (originally in The International Journal of Orthodontia, Oral Surgery and Radiography.) 1922; 8(2):61-64.

- Crozat, George. The Crozat Philosophy of Treatment, Monograph, New Orleans, 1-8.

- Rogers, AP. Stimulating arch development by the exercise of the masseter-temporal group of muscles. Am J. Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. (originally in The International Journal of Orthodontia, Oral Surgery and Radiography.) 1922; 8(2):61-64.

- Oktay H, Ulukaya E. Maxillary Protraction Appliance Effect on the Size of the Upper Airway Passage, Angle Orthod. 2008; 78(2):209-214.

- Singh GD, Garcia-Motta AV, Hang WM. Evaluation of the posterior airway space following Biobloc therapy: geometric morphometrics. Cranio. 2007;25(2): 84-89.

- Villa MP, Bernkopf E, Pagani J, Broia V, Montesano M, Ronchetti R. Randomized controlled study of an oral jaw-positioning appliance for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children with malocclusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(1):123-127.

- Wang Q, Jia P, Anderson NK, Wang L, Lin J. Changes of pharyngeal airway size and hyoid bone position following orthodontic treatment of Class I bimaxillary protrusion, Angle Orthod. 2012;82(1):115-121.

- Li AM, Wong E, Kew J, Hui S, Fok TF. Use of tonsil size in the evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea, Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(2):156-159.

- Marcus CL, Brooks LJ, Draper KA, Gozal D, Halbower AC, Jones J, Schechter MS, Ward SD, Sheldon SH, Shiffman RN, Lehmann C, Spruyt K. Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):3714-755.

- Pitta DBeS, Pessoa AF, Sampaio ALL, Rodrigues RN, Tavares MG, Tavares P, et al. Oral Myofunctional therapy applied on two cases of severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;11(3):350-354.

- Puhan MA, Suarez A, Lo Cascio C, Zahn A, Heitz M, Braendli O. Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):266-270.

- Litchfield, PM. Respiratory fitness and acid-base regulation. Psychophysiology Today. 2010; 7(1): 6-12. https://betterphysiology.com/download/softwareupdates/Respiratory%20Fitness%202010%20Litchfield2.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- Birch M. Sleep apnoea: a survey of breathing retraining. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(4):40-41.

- Chandra RK, Patadia MO, Raviv J. Diagnosis of nasal airway obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am.2009; 42(2):207–225.

- Kotlow L. infant reflux and aerophagia associated with the maxillary lip-tie and ankyloglossia (tongue-tie). Clinical Lactation. 2011;2(4):25-29.

- Mew, M. Craniofacial dystrophy: a possible syndrome? Br Dent J. 2014;216(10):555-558.

- Guimarães KC, Drager LF, Genta PR, Marcondes BF, Lorenzi-Filho G. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(10):962-966.

- Ritz T, Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Changes in pCO2, symptoms, and lung function of asthma patients during capnometry-assisted breathing training. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009;34(1):1–6.

- Litchfield, PM. Respiratory fitness and acid-base regulation. Psychophysiology Today. 2010; 7(1): 6-12. https://betterphysiology.com/download/softwareupdates/Respiratory%20Fitness%202010%20Litchfield2.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- Hosoya H, Kitaura H, Hashimoto T, Ito M, Kinbara M, Deguchi T, Irokawa T, Ohisa N, Ogawa H, Takano-Yamamoto T. Relationship between sleep bruxism and sleep respiratory events in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breathe. 2014;18(4):837-844.

- Gelb ML. Airway centric TMJ philosophy. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2014;4(8): 551- 562.

- James GA, Strokon D . an introduction to cranial movement and orthodontics. Int J Orthod Milwaukee. 2005;16(1):23-26.

- Mew, M. Craniofacial dystrophy: a possible syndrome? Br Dent J. 2014;216(10):555-558.

- Huang YS, Guilleminault C. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea and the critical role of oral-facial growth: evidences. Front Neurol. 2013;Jan 22(3):184.

- Campbell C, Jacobson H. Whole: Rethinking the Science of Nutrition. Dallas, Texas: BenBella Books; 2013.

- McNamara J, ed. Early orthodontic treatment: is the benefit worth the burden? U. Michigan Press, 2007.