CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This clinical article aims to discuss protocols for determining esthetic considerations for the potential adult orthodontic patient.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking this quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article.

Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify what conditions could be considered “cosmetic” alignment and which fall into the scope of an orthodontic specialist.

- Recognize the effect that root angulations have on prospective treatment.

- Realize the effect that crown width and length have on prospective treatment.

- Identify how bone levels are a factor for proper correct incisal edge position, occlusion, and crown-to-root relationships.

- Discuss the possible ramifications to overjet, overbite, and incisal edges on treatment outcomes.

- Identify the characteristics of gingival levels and form.

- Identify some solutions to black triangles.

Dr. Thomas Sealey says it is essential to identify what cases are suitable for “cosmetic” alignment and which fall into the scope of practice of the specialist orthodontic practitioner

Figures released by the British Orthodontic Society (BOS) reveal the rising number of adults seeking orthodontic treatment in the United Kingdom. A survey conducted in June 2016, designed to gather data about adult orthodontics in the UK, was sent to BOS members working in high street practices. Three-quarters of them reported that they had seen an increase in adult treatment, with the main reasons for seeking treatment being a heightened awareness of adult orthodontics in the UK, alongside rising expectations on how treatment can positively impact both appearance and well-being. Of the adult patients in these mixed and private practices, 66% of patients are 26-40 year olds, and 22% are 41-55. More than 10% are 18-25.

With more adults seeking treatment and more general dentists learning about simple orthodontic techniques, it is even more important than ever to know which cases are suitable for “cosmetic” alignment and which fall into the scope of practice of the specialist orthodontic practitioner. Most “cosmetic” systems have protocols in place to help general dentists filter out the cases that are above and beyond their level of training, with positive encouragement for patient referral to the specialist centers. If protocols are followed, then both general and specialist practitioners can benefit hugely from the increasing volume of adult patients seeking orthodontic therapy.

When any case is deemed suitable for practitioners to begin alignment, whatever their skill level, there are still a number of challenges that any cosmetic dentist or orthodontic specialist must consider before starting treatment. Orthodontic finishing is a continual challenge for most practitioners. In some situations, especially in younger teeth, the alignment relationship seems to correct itself with very little intervention on the part of the clinician. However, in older patients, there are many more challenges to overcome. Examples follow:

- How should the teeth be positioned if the patient will require minor or major restoration of the teeth after orthodontic treatment?

- How should the clinician finish the occlusion if the patient has had significant periodontal bone loss before orthodontic therapy?

- How can the esthetics of a debilitated adult dentition be improved to resemble the non-worn, non-restored, non-periodontally involved adolescent dentition?

The majority of these adult patients are not expecting perfection. They have no concept or indeed no desire to achieve an Angle’s Class 1; they just want a nice smile and nice front teeth that are even and symmetrical. Their expectations are usually focused on their front teeth only, which makes our lives as practitioners potentially much easier. If we do not need to worry about their posterior teeth and their occlusal scheme, and attention shifts to only their upper or lower anterior segment, then finishing of such cases gets a whole lot more predictable.

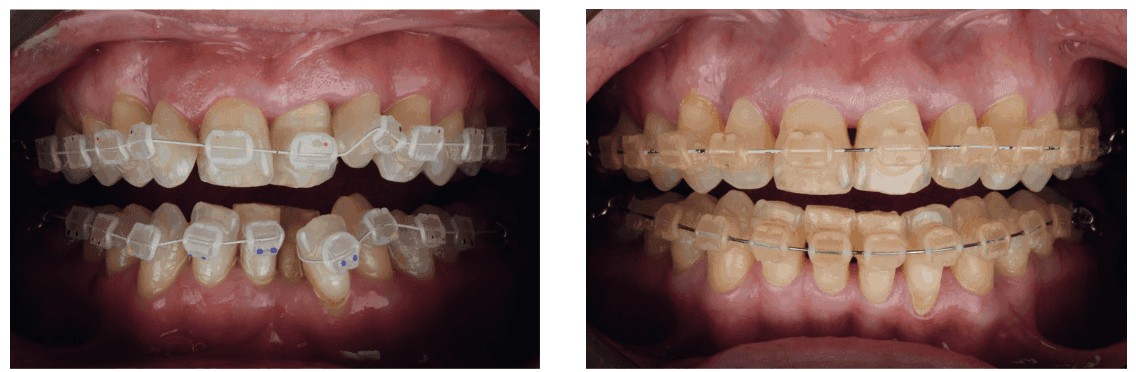

If the esthetics of the patients’ smile is their main driving factor, then final esthetics need to be considered before any orthodontic movement begins. Things to assess are root angulation, bone levels, overbite, overjet, incisal edges, crown length/width, gingival levels/form, and black triangles. These all need assessment and predictions made regarding the end-situation after alignment, so that we can plan into our treatment times and costs for our patients to allow for and consider how any of the above will affect the final outcome. Imagine the consequences of a case like the example in Figures 1 and 2 where considerations and costs were not given pretreatment for the closure of the black triangles that would develop, as well as the leveling of the incisal edges after arch alignment. Careful planning, explanation, and consent are paramount.

Root angulation

Close root proximity after orthodontic treatment will cause problems in certain restorative patients. If the roots of anterior teeth are in close proximity, and it is planned that the patient will have full crowns or veneers placed afterwards, it may be difficult to obtain an adequate impression of the gingival margins of adjacent tooth preparations or to pack impression cord into the sulcus if the adjacent tooth root is in close contact in the cervical region of the tooth preparation. Another situation where root angulation is important is in the single-tooth implant patient, where space between the roots is needed for the planned implant placement. This type of tooth movement may require several months of adjustment to establish adequate space for the implant.

Bone levels

The orthodontist should align the incisal edges of non-worn, non-restored anterior teeth and the marginal ridges of non-worn, non-restored posterior teeth in the adolescent patient; this way the cementoenamel junctions and interproximal bone will be at the appropriate level. In adult patients with prior periodontal disease and interproximal bone loss, the incisal edges or marginal ridges of the teeth are not reasonable guides for vertical positioning of adjacent teeth (Kokich 2002).1 If the patient has horizontal bone loss in the maxillary or mandibular anterior regions, it is best to align the bone levels rather than adjacent teeth. In these situations, equilibration of the incisal edges, as the bone is leveled, is recommended to establish the correct incisal edge position, occlusion, and crown-to-root relationships.

Crown width/length

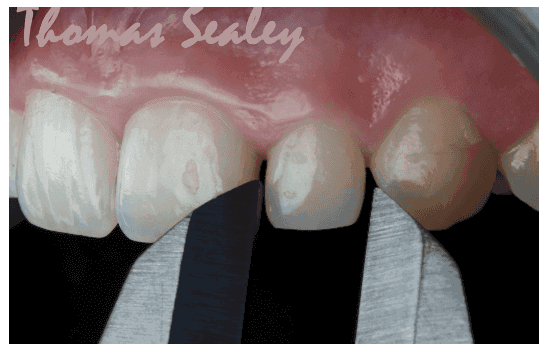

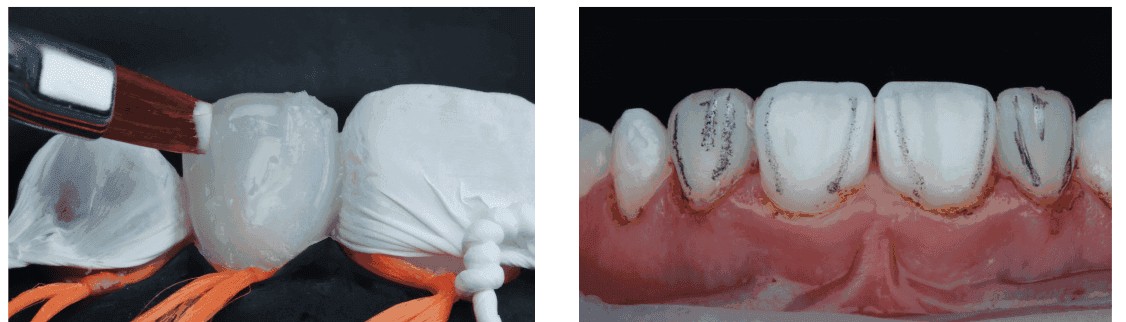

Malformed laterals generally have two different shapes: Some are cone-shaped, and others resemble the shape of a normal lateral incisor, but are significantly narrower, thinner, and shorter. If a lateral incisor is only slightly narrower than normal, and the problem is bilateral, the orthodontist may decide not to provide space to restore the tooth during orthodontic treatment. If the width discrepancy is only slight, the influence on the anterior occlusion, and the impact on esthetics may be indistinguishable (Kokich, et al., 1999).2 However, if the malformation is unilateral, or if the width discrepancy is significant, esthetics and occlusion could be adversely affected if the malformed tooth or teeth are ignored (Lombardi 1973; Ricketts 1982; Chiche and Pinault 1994).3,4,5 Either composite or porcelain veneer restoration, or complete composite or porcelain crowns may be bonded to the enamel with minimal tooth reduction. However, the orthodontist must position the malformed tooth in the proper position to facilitate ideal restoration. Figures 3-5 show how orthodontics was used to develop spacing around bilateral microdontic lateral incisors, a common occurrence in UK teeth, and then how simple no-prep composite bonding was used to restore the esthetics of these teeth.

Overjet, overbite, and incisal edges

Anterior overjet is defined as the distance between the labial-incisal edges of the maxillary incisors and canines and the lingual surfaces of the maxillary incisors and canines. The practitioner must be aware that, in many Angle Class II Division 2 patients, there will be an increase in overjet and a decrease in overbite as the upper arch rounds out. These changes must be explained and consented before alignment begins. If the patient does not accept this, then this would be a situation to refer to an orthodontic specialist.

Another situation where overjet must be produced during orthodontic finishing is in the patient who has significant tooth abrasion or erosion of the labial surfaces of the mandibular incisors or lingual surfaces of the maxillary anterior teeth. As teeth wear, they usually erupt to maintain contact with the opposing arch. If these teeth are finished in occlusion with the teeth in contact, there will be no space for the dentist to restore the tooth surface loss. In these situations, the method of creating the space often involves intrusion of the eroded or abraded incisors to create the overjet.

It is possible to intrude up to four maxillary incisors by using the posterior teeth as anchorage during the intrusion process. This process is accomplished by placing the orthodontic brackets as close to the incisal edges of the maxillary incisors as possible. The brackets are placed in their normal position on the canines and remaining posterior teeth. The patient’s posterior occlusion will resist the eruption of the posterior teeth, and the incisors will gradually intrude and move the gingival margins and the crown apically. This creates the restorative space necessary to place bonded composite restorations on the abraded surfaces to re-establish contact with the opposing arch.

Gingival levels and form

The relationship of the gingival margins of the six maxillary anterior teeth plays an important role in the esthetic appearance of the crowns (Kokich, et al., 19846; Kokich 1990, 1993, 1996, 19977,8,10,11; Chiche, et al., 19949). Four characteristics contribute to ideal gingival form. First, the gingival margins of the two central incisors should be at the same level. Second, the gingival margins of the central incisors should be positioned more apically than the lateral incisors and should be at the same level as the canines. Third, the contour of the labial gingival margins should mimic the cementoenamel junctions of the teeth. Last, there should be a papilla between each tooth, and the height of the tip of the papilla is usually halfway between the incisal edge and the labial gingival height of contour over the center of each anterior tooth. Therefore, the gingival papilla occupies half of the interproximal contact, and the adjacent teeth form the other half of the contact.

When gingival form is wrong, the teeth have that classic “perio” look, so it is important to maintain the correct relationships of the teeth to ensure symmetry and form. When gingival margin discrepancies are present, the clinician must determine the proper solution for the problem — orthodontic movement to reposition the gingival margins or surgical correction of gingival margin discrepancies. To make the correct decision, it is necessary to evaluate four criteria. First of all, the relationship between the gingival margin of the maxillary central incisors and the patient’s lip line should be assessed when the patient smiles. If a gingival margin discrepancy is present, but the patient’s lip does not move upward to expose the discrepancy, it does not require correction. If a gingival margin discrepancy is apparent, the next step is to evaluate the labial sulcular depth over the two central incisors. If the shorter tooth has a deeper sulcus, excisional gingivectomy may be appropriate to move the gingival margin of the shorter tooth apically. Figures 6 and 7 show the use of a laser to correct gingival margin discrepancies and to improve the symmetry of the anterior segment. However, if the sulcular depths of the short and long incisors are equivalent, gingival surgery will not help.

Black triangles

Occasionally, adults will have open gingival embrasures or black triangles between their central incisors, especially after crowding is relieved using orthodontics. This space is usually due to one of three causes: tooth shape, root angulation, or periodontal bone loss. Most open embrasures between the central incisors are due to problems with tooth contact. The first step in the diagnosis of this problem is to evaluate a periapical radiograph of the central incisors. If the root angulation is divergent, then the brackets should be repositioned, so the root position can be corrected. In these situations, the incisal edges may be uneven and require restoration with either composite or porcelain restorations. If the periapical radiograph shows that the roots are in their correct relationship, then the open gingival embrasure is due to triangular tooth shape.

If the shape of the tooth is the problem, two solutions are possible. One possibility is to restore the open gingival embrasure using composite bonding techniques such as the Clark Anterior Matrix System (BioClear, Optident Ltd.). The other option is to reshape the tooth by flattening the incisal contact and then closing the space. This will result in lengthening of the contact until it meets the papilla. In addition, if the embrasure space is large, closing the space will squeeze the papilla between the central incisors. This will help create a one-to-one relationship between the contact and papilla, and to restore uniformity to the heights between the midline and adjacent papillae.

Conclusion

The best advice that can be given would be to “start with the end first.” If you first design your final end-esthetic outcome to meet the patient expectations, and then work backwards from there, then you’ll be sure to plan correctly, appropriately cost your time and procedures, and properly explain and consent your patients for the whole treatment — never leaving yourself in the difficult situation where the teeth are straight but the patient still isn’t happy with his/her smile.

Using a technique usually reserved for the adult orthodontic patient, Drs. Gorton and Bekmezian discuss a treatment for mixed dentition patients. Read about it here.

References

- Kokich VG. The role of orthodontics as an adjunct to periodontal therapy, in Newman MG, Carranza FA, Takei H (eds): Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology, 9th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Inc.; 2002.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak A, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11(6):311-324.

- Lombardi R. The principles of visual perception and their clinical application to denture esthetics. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;29(4):358-382.

- Ricketts RM. The biologic significance of the divine proportion and Fibronacci series. Am J Orthod. 1982;81(5):351-370.

- Chiche G, Pinault A. Replacement of deficient crowns. In: Pinault A, Chiche G, eds. Esthetics of Anterio Fixed Prosthodontics. 1st ed. Chicago, IL: Quintessence; 1994.

- Kokich VG, Nappen D, Shapiro P. Gingival contour and clinical crown length: their effect on the esthetic appearance of maxillary anterior teeth. Am J Orthod. 1984;86(2):89-94.

- Kokich V. Enhancing restorative, esthetic and periodontal results with orthodontic therapy. In: Schluger S, Youdelis R, Page R, et al., eds. Periodontal Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1990.

- Kokich VG. Anterior dental esthetics: an orthodontic perspective I. crown length. J Esthet Dent. 1993;5:19-23.

- Chiche G, Kokich V, Caudill R. Diagnosis and treatment planning of esthetic problems. In: Pinault A, Chiche G, eds. Esthetics in Fixed Prosthodontics. Chicago, IL: Quintessence; 1994.

- Kokich VG. Esthetics: the orthodontic-periodontic restorative connection. Semin Orthod. 1996;2(1):21-30.

- Kokich VG. Esthetics and vertical tooth position: orthodontic possibilities. Compendium Contin Educ Dent. 1997;18(12):1225-1231.

- Kokich VG. Excellence in finishing: modifications for the perio-restorative patient. Semin Orthod. 2003;9(3):184-203.

Dr. Thomas Sealey, Bchd (2006), MMedEd, MSc Endo, has a special interest in achieving cosmetic smile makeovers using a minimally invasive approach. He lectures on his techniques internationally and has extensive experience in all aspects of cosmetic dentistry — utilizing orthodontics, advanced esthetic composite restorations, and ceramic smile design — to achieve perfectly natural smile transformations. He holds master degrees in both Endodontic Practice and in Medical Education and is the inventor of the ‘”Single visit Orthodontic Lingual and Invisible Dual” (SOLID) retention system. He won in four categories at the recent 2018 UK Aesthetic Dentistry Awards and has won “Best Young Dentist – South East” for 2 consecutive years at the 2015 and 2016 FMC UK Dentistry Awards. Dr. Sealey graduated from Leeds University in 2006 and is currently joint-owner of a private cosmetic dental practice called “Start-Smiling” in Ingatestone, Essex, England.

Dr. Thomas Sealey, Bchd (2006), MMedEd, MSc Endo, has a special interest in achieving cosmetic smile makeovers using a minimally invasive approach. He lectures on his techniques internationally and has extensive experience in all aspects of cosmetic dentistry — utilizing orthodontics, advanced esthetic composite restorations, and ceramic smile design — to achieve perfectly natural smile transformations. He holds master degrees in both Endodontic Practice and in Medical Education and is the inventor of the ‘”Single visit Orthodontic Lingual and Invisible Dual” (SOLID) retention system. He won in four categories at the recent 2018 UK Aesthetic Dentistry Awards and has won “Best Young Dentist – South East” for 2 consecutive years at the 2015 and 2016 FMC UK Dentistry Awards. Dr. Sealey graduated from Leeds University in 2006 and is currently joint-owner of a private cosmetic dental practice called “Start-Smiling” in Ingatestone, Essex, England.