CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss diagnosis and preventative treatment for partially displaced canines.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions with the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize the incidence of ectopic eruption of maxillary canines.

- Recognize some reasons for partially displaced canines (PDCs).

- Realize some ways to identify PDCs.

- See some radiographic indications of PDCs.

- Identify some preventative treatment for PDCs.

Drs. Harold Rosenberg, Austin Chen, and Shervin Abbaszadeh discuss early detection and diagnosis of PDCs

Ectopic eruption is defined as a disturbance in which a tooth does not follow its usual path of eruption.1 Maxillary canines are one of the most common ectopically erupting teeth, second only to third molars2; and of importance, once displaced palatally, most result in impactions.3,4 The ratio of palatal to buccal canine impactions is 8:1 and is twice as common in females than males,5-7 with a total reported prevalence of between 0.8%-5.2% of the population.8

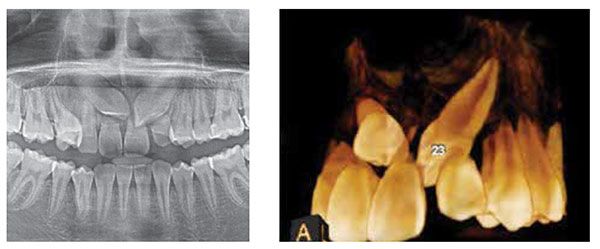

Palatally displaced canines (PDCs) can be associated with significant resorption of adjacent teeth9-11 (Figures 1A-1B). Furthermore, the treatment of canines, when they become impacted often involves surgical exposure of the tooth (Figure 2) and the need for subsequent forced orthodontic eruption. This type of treatment can have associated morbidity such as root resorption, bone loss, recession, necrosis, and can lead to prolonged orthodontic treatment time and cost.12 Therefore, preventive treatment to avoid subsequent impaction of maxillary canines becomes an important tool so that patients can be spared these negative consequences alongside potential surgery and prolonged orthodontic treatment. As such, early detection and diagnosis by the primary care dentist is of utmost importance so that appropriate interceptive treatment can be prescribed when indicated.

Diagnosis of palatally displaced canines

On average, the maxillary permanent canines erupt between the ages of 11 to 12, usually earlier in females than males.13 Assessment of the maxillary canines should begin by the age of 8, with a visual inspection and palpation for a canine bulge (Figure 3). Positive palpation of a canine bulge on the buccal typically correlates to approximately a 92% positive chance that the canine will erupt normally.14,15 A non-palpable maxillary buccal canine bulge after the age of 10 years and beyond should be considered abnormal16 and is an indication of a palatally displaced canine (Table 1). Assessment of the degree of mobility of the primary canine is also important starting at this age.

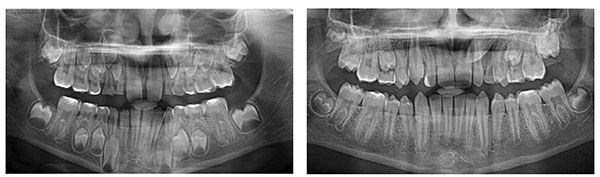

Mobility of the primary canine indicates that the tooth is undergoing physiological root resorption, which is most likely due to a normally erupting permanent canine. In addition, radiographic investigations such as panoramic, periapical, or maxillary occlusal films can be considered when there is doubt to the whereabouts of the permanent canine. Panoramic radiographs can provide two pieces of information that are important in determining impaction. First is the absence of physiologic root resorption of primary canines, as ectopically positioned permanent canines typically do not cause resorption of the primary canine roots.

Mobility of the primary canine indicates that the tooth is undergoing physiological root resorption, which is most likely due to a normally erupting permanent canine. In addition, radiographic investigations such as panoramic, periapical, or maxillary occlusal films can be considered when there is doubt to the whereabouts of the permanent canine. Panoramic radiographs can provide two pieces of information that are important in determining impaction. First is the absence of physiologic root resorption of primary canines, as ectopically positioned permanent canines typically do not cause resorption of the primary canine roots.

Second, radiographs provide assessment of the horizontal overlap of the canine crown over the root of the lateral incisor (Figures 4A-4B). The more overlap there is, and the more the canine crown is positioned toward the midline, the poorer the prognosis for spontaneous correction and the greater the probability of impaction occurring.16-18

Other radiographic findings associated with PDCs include an increased mesial inclination (>15°) of the canine long axis with the midline and a distally positioned canine apex16 (Table 1).

Preventive treatment for palatally displaced canines

The most documented and common preventive treatment for PDCs is the extraction of the primary canine. In a classic observation study (no control group was used for comparison), Ericson and Kurol prospectively studied 35 children aged 10 to 13 who had PDCs and showed successful eruption of the permanent canines after extraction of the primary canines in 78% of cases.19 The success of the interceptive extractions depended on the extent of radiographic overlap of the permanent canine over the lateral incisor. If the crown of the permanent canine was overlapping distal to the midline of the lateral incisor root, the primary canine extraction normalized the eruption of the permanent canine in 91% of the cases. Otherwise, only 64% of canines normalized after extraction of the primary canines if they were mesial to the midline of the lateral incisor root.

Subsequent well-controlled studies of preventive treatment of PDCs have combined the extractions of maxillary primary canines with the extraction of primary first molars,20 concomitant use of headgear (HG)4,21 and subsequent use of rapid maxillary expansion (RME).22

Another study used a combination of RME and HG without maxillary primary canine extraction as preventive treatment of PDCs.23 For the purpose of this paper and for ease of clinical application, we will limit our discussion to preventive treatment of PDCs to: 1) the extraction of maxillary primary canines only,24 2) the extraction of maxillary primary canines in combination with headgear,21 and 3) the extraction of maxillary primary canines in combination with rapid maxillary expansion (RME) and/or transpalatal arch (TPA).22 Furthermore, included studies will be limited to prospective randomized controlled studies that included untreated controls for comparison and used the eruption of the PDC as the final outcome measure.

Randomized controlled trials on preventive treatment of PDCs

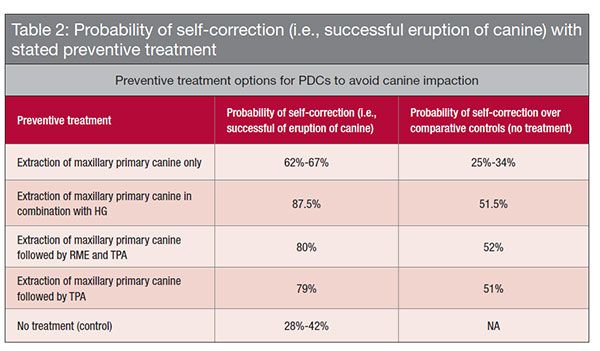

Results of the selected studies have been summarized in Table 2.

Extraction of maxillary primary canine

Extraction of maxillary primary canine

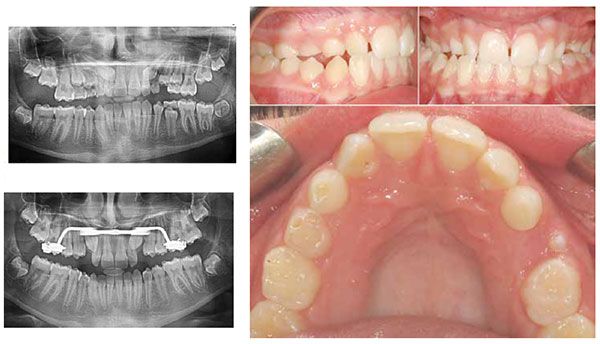

It was documented in a prospective randomized controlled study on the effect of interceptive extraction of primary canines on palatally displaced maxillary canines that the rates of successful eruption of the PDCs at extraction and control sites were 67% and 42%, respectively, after an 18-month interval.24 What was unique about this study was the fact that each individual acted as their own control. This was possible by only including bilateral PDC cases and randomly assigning one of the two primary canines for extraction while the other side served as a control. Incidentally, only 8% of palatal canine impactions are bilateral.25 Of interest was the fact that this was most effective if the primary canine was extracted early at the age of 10 to 11 years. Furthermore, the authors recommended maintenance of the upper arch perimeter with the use of a transpalatal arch space-holding device. Applying this to a clinical scenario, if a PDC is identified clinically by the absence of a buccal canine bulge and radiographically by the overlap of the erupting permanent canine over the permanent lateral incisor, then extraction of the primary maxillary canine will improve the chance of self-correction and decrease the probability of impaction by 25%. Cases showing the absence of other orthodontic problems such as crossbites, excess overjet, deep overbites, crowding, and spacing are good candidates for this type of treatment (Figures 5A-5B). Nevertheless, space maintenance or space opening after extraction of the primary canine may be recommended.

Extraction of maxillary primary canine in combination with headgear

A randomized clinical study comparing the effect of extraction of maxillary primary canines with and without headgear showed that the additional use of a headgear resulted in a significantly higher probability of successful eruption (87.5%) over extraction of the primary canine alone (65.2%).21 Both treatment modalities resulted in a higher percentage of self-correction and eruption of the PDCs over the control group receiving no treatment (36%). Interestingly, for the primary canine extraction group the percentage of successful cases in this study (65.2%) was in agreement with the successful cases reported in the prospective RCT discussed previously (67%).24 The authors reported a mesial drifting of first molars in both the extraction-only and control groups and attribute the higher percentage of successful cases in the headgear group to minimizing mesial drift of the maxillary first molars thus maintaining space for the eruption of the canines.

An earlier study by the same authors documented an 80% probability of successful eruption of PDCs in patients who had the primary canines extracted combined with headgear treatment.4 In contrast, only 50% of PDCs successfully erupted when the primary canines were extracted as an isolated measure to intercept PDCs, which was not significantly greater than the success in untreated controls. When applying this data to clinical practice, a case exhibiting PDCs with a Class II occlusion and excess overjet may be an ideal candidate for this interceptive treatment approach (Figures 6A-6D).

Extraction of maxillary primary canine in combination with RME

A study to investigate the effect of rapid maxillary expansion (RME) and/ or transpalatal arch (TPA) therapy in combination with deciduous canine extraction (CE) on the eruption of palatally displaced canines showed successful eruption of these canines in 80% of cases for the RME/TPA/CE group.22 When the extraction of deciduous canines was coupled with a TPA appliance to hold back the first permanent molars, the success of eruption was 79%, whereas extraction of the primary canine alone resulted in self-correction and eruption in 62.5% of cases. In contrast, only 28% of cases in the control group receiving no interceptive treatment resulted in self-correction/eruption. Of significance was the fact that PDCs with a fully developed root demonstrated significantly less probability of successful eruption following interceptive treatment. This outlines the importance of early detection of PDCs to allow for the provision of successful interceptive treatment. Given the findings of this study, extraction of maxillary primary canines in combination with RME may be best suited to cases in which there are other findings present that warrant maxillary expansion (posterior crossbite, transverse discrepancy, narrow maxillary arch with crowding, etc.) (Figures 7A-7C).

Clinical recommendations

Early detection and diagnosis of PDCs is crucial in the prevention of impacted canines. The primary care dentist is in a great position to screen patients at the ages of 8 to 11 by simple clinical palpation of the maxillary buccal canine bulge and radiographic evaluation of the maxillary erupting canines. The absence of a buccal canine bulge intraorally and the presence of an erupting canine crown that is overlapping the maxillary lateral incisor on a radiograph are evidence of a palatally displaced maxillary canine. This finding should raise a flag and initiate a conversation with the patient’s parents regarding preventive treatment to avoid future impaction. With no treatment, one can expect self-correction and successful eruption in merely 30% to 40% of cases. In other words, as many as 70% of these PDCs will become impacted. However, by extracting the maxillary primary canine, the probability of self-correction increases to around 65%; and when coupled with a headgear or expansion appliance/TPA, the probability of self-correction further increases to 87.5% and 80% respectively. Nevertheless, because successful self-correction and eruption of the permanent canine can take as long as 18 months, a long observation period is required to monitor the eruption of these teeth.

This article was reprinted with permission from September 2015 Oral Health.

References

- Yaseen SM, Naik S, Uloopi KS. Ectopic eruption – a review and case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2011;2(1):3-7.

- Shah RM, Boyd MA, Vakil TF. Studies of permanent tooth anomalies in 7,886 Canadian individuals. Dent J. 1978; 44(6): 262-264.

- Power SM, Short MB. An investigation into the response of palatally displaced canines to the removal of deciduous canines and an assessment of factors contributing to a favorable eruption. Br J Orthod. 1993; 20(3): 215-223.

- Leonardi M, Armi P, Franchi L, Baccetti T. Two interceptive approaches to palatally displaced canines: a prospective longitudinal study. Angle Orthod. 2004;74(5):581-586.

- Ericson S, Kurol J. Radiographic examination of ectopically erupting maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987; 91(6):483-492.

- Hitchin AD. The impacted maxillary canine. Br Dent J. 1956; 100:1-14.

- Dachi SF, Howell FV. A survey of 3,874 routine full mouth radiographs. II. A study of impacted teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1961; 14: 1165-1169.

- Thilander B, Jakobsson SO. Local factors in impaction of maxillary canines. Acta Odontol Scand. 1968; 26(2): 145-168.

- Rimes RJ, Mitchell CN , Willmot DR. Maxillary incisor root resorption in relation to the ectopic canine: a review of 26 patients. Eur J Orthod. 1997;19(1): 79–84.

- Ericson S, Kurol J. Resorption of incisors after ectopic eruption of maxillary canines: a CT study. Angle Orthod. 2000;70(6): 415–423.

- Ericson S, Bjerklin K, Falahat B. Does the canine dental follicle cause resorption of permanent incisor roots? A computed tomographic study of erupting maxillary canines. Angle Orthod. 2002;72(2): 95–104.

- Bishara SE, Kommer DD, McNeil MH, Montagana LN, Oesterle, LJ, Youngquist HW. Management of impacted canines. Am J Orthod. 1976; 69(4): 371-387.

- Wedl JS, Schoder V, Blake FA, Schmelzle R, Friedrich RE. Eruption times of permanent teeth in teenage boys and girls in Izmir (Turkey). J Clin Forensic Med. 2004; 11(6): 299-302.

- Kettle MA. Treatment of the unerupted maxillary canine. Trans Br Soc Orthod. 1957; 32:74-84.

- Ericson S, Kurol J. Longitudinal study and analysis of clinical supervision of maxillary canine eruption. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986; 14(3):172-176.

- Counihan K, Al-Awadhi EA, Butler J. Guidelines for the assessment of the impacted maxillary canine. Dent Update. 2013; 40(9):770–777.

- McSherry P. The assessment of and treatment options for the buried maxillary canine. Dent Update. 1996;23(1):7-10.

- Pitt S, Hamdan A, Rock P. A treatment difficulty index for unerupted maxillary canines. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28(2):141-144.

- Ericson S, Kurol J. Early treatment of palatally erupting maxillary canines by extraction of the primary canines. Eur J Orthod. 1988;10(4):283-295.

- Alessandri Bonetti G, Zanarini M, Incerti Parenti S, Marini I, Gatto MR. Preventive treatment of ectopically erupting maxillary permanent canines by extraction of deciduous canines and first molars: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139(3):316-323.

- Baccetti T, Leonardi M, Armi P. A randomized clinical study of two interceptive approaches to palatally displaced canines. Eur J Orthod. 2008; 30(4):381-385.

- Baccetti T, Sigler LM, McNamara JA Jr. An RCT on treatment of palatally displaced canines with RME and/or a transpalatal arch. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33(6):601-607.

- Armi P, Cozza P, Baccetti T. Effect of RME and headgear treatment on the eruption of palatally displaced canines: a randomized clinical study. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(3):370–374.

- Bazargani F, Magnuson A, Lennartsson B. Effect of interceptive extraction of deciduous canine on palatally displaced maxillary canine: a prospective randomized controlled study. Angle Orthod. 2014; 84(1):3-10.

- Litsas G, Acar A. A review of early displaced maxillary canines: etiology, diagnosis and interceptive treatment. Open Dent J. 2011; 5:39-47.