CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss presurgical nasoalveolar molding for treatment of cleft palate in newborns.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Discuss some accepted treatment approaches for cleft conditions.

- Identify the technique using presurgical nasoalveolar molding (PNAM).

- Recognize some appliances needed for the PNAM procedure.

- Recognize some clinical procedures for correction of the unilateral cleft using the NAM appliance.

- Identify some physical reactions to look for during treatment to ensure that the infant is reacting well to the technique.

Dr. Thomas Wilson discusses an effective technique that can minimize the extent of surgery to repair cleft palate in newborns

One of the most challenging conditions confronting the craniofacial healthcare team is treatment of cleft lip and palate. The many functional, esthetic, psychological, and sociological issues resulting from clefts and related craniofacial anomalies require a team approach using the expertise of professionals in many healthcare disciplines. A successful treatment result will depend on a combination of surgical, orthodontic/orthopedic, and restorative care, as well as speech therapy and ongoing maintenance of the dentition.

Treatment approaches and timing for cleft conditions remain a matter of debate even in our current era of advanced technology and knowledge. The basic goal of any approach to cleft lip, alveolus, and palate repair is to restore normal anatomy. Ideally, deficient tissues should be expanded, and malpositioned structures should be repositioned prior to surgical correction. This provides the foundation for a less invasive surgical repair. Historically, the use of pre-surgical infant orthopedic (PSIO) appliances or molding plate therapy has helped reduce the size of clefts of the alveolus and hard palate prior to surgery. Since its introduction by McNeil (McNeil, 1950), various techniques have been described for bringing the intraoral alveolar segments closer together in unilateral and bilateral cleft patients (Mylin 1969; Latham 1980).

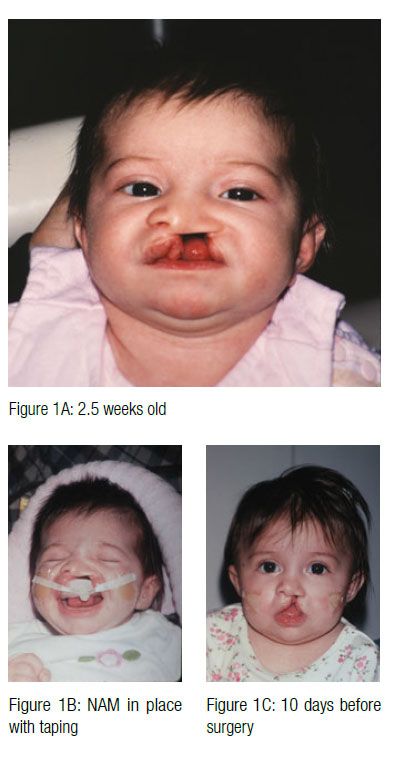

In 1997, Drs. Barry H. Grayson and Court B. Cutting at the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at New York University Medical Center developed a new approach of pre-surgical nasoalveolar molding (PNAM). PNAM includes not only reduction of the size of the intraoral alveolar cleft through the molding of the bony segments, but also the active molding and positioning of the surrounding soft tissues affected by the cleft, including the deformed soft tissue and cartilage in the cleft nose. This is accomplished through the use of a nasal stent that is based on the labial flange of a conventional oral molding plate and enters the nasal aperture.

In 1997, Drs. Barry H. Grayson and Court B. Cutting at the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at New York University Medical Center developed a new approach of pre-surgical nasoalveolar molding (PNAM). PNAM includes not only reduction of the size of the intraoral alveolar cleft through the molding of the bony segments, but also the active molding and positioning of the surrounding soft tissues affected by the cleft, including the deformed soft tissue and cartilage in the cleft nose. This is accomplished through the use of a nasal stent that is based on the labial flange of a conventional oral molding plate and enters the nasal aperture.

The stent provides support and gives shape to the nasal dome and alar cartilages. Presurgical nasoalveolar molding may be successfully employed in the early management of both the unilateral and bilateral cleft anomalies in newborns. These new techniques greatly improve upon the results usually achieved through traditional cleft palate appliances. The result is an overall improvement in the esthetics of the nasolabial complex, while minimizing the extent of surgery and the overall number of surgical procedures.

Clinical procedures for correction of the unilateral cleft using the NAM appliance

As soon as possible after birth, the infant is scheduled for an exam, and an impression of the cleft is made using a polyvinylsiloxane material. The impression is obtained with the infant awake and without any anesthesia. Care is taken to ensure that the material has reproduced the borders as well as the cleft area. The infant should be able to cry during the impression procedure. If no crying is heard, the airway is blocked.

The impression is then poured in stone and trimmed. The cleft region of the palate and the alveolus can be filled with wax or silly putty to approximate the contour of an intact arch prior to fabrication of the molding appliance. The appliance is then made using clear orthodontic resin with a thickness of 3 mm to 4 mm.

The impression is then poured in stone and trimmed. The cleft region of the palate and the alveolus can be filled with wax or silly putty to approximate the contour of an intact arch prior to fabrication of the molding appliance. The appliance is then made using clear orthodontic resin with a thickness of 3 mm to 4 mm.

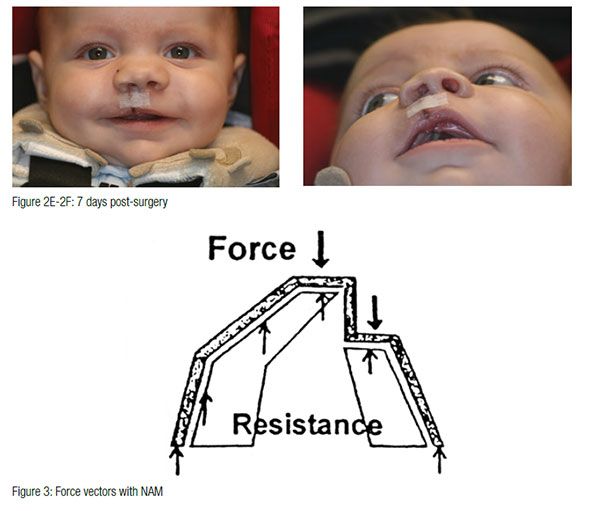

The appliance is mainly retained through extraoral facial tape and elastics. Also, no acrylic material should project into the cleft areas, as this will block the intended movement of the alveolar segments into their desired presurgical positions. The infant must be able to easily feed without gagging or struggling. If gagging is noted, the posterior extent of the appliance should be reduced. At the second appointment, if the infant is doing well, the appliance is modified to begin molding the alveolar cleft segments. This is accomplished through selective removal of acrylic from the area where the alveolar bone is to move. At the same time, a soft denture reline material is added to the area where bone is to be moved. These minor adjustments are made weekly. The ultimate goal of this sequential addition and selective grinding away of material is to reduce the size of the cleft gap and to have the two segments of alveolus contact with proper maxillary form. At this same appointment, an external retentive button is added at the site of the cleft. This retentive button helps seat the appliance and secure the retentive lip tapes and elastic bands (Figure 3). The taping of the cleft lip segments also serves to improve the alignment of the nasal base region by bringing the columella toward the midsagittal plane and improving the symmetry of the nose.

The appliance is mainly retained through extraoral facial tape and elastics. Also, no acrylic material should project into the cleft areas, as this will block the intended movement of the alveolar segments into their desired presurgical positions. The infant must be able to easily feed without gagging or struggling. If gagging is noted, the posterior extent of the appliance should be reduced. At the second appointment, if the infant is doing well, the appliance is modified to begin molding the alveolar cleft segments. This is accomplished through selective removal of acrylic from the area where the alveolar bone is to move. At the same time, a soft denture reline material is added to the area where bone is to be moved. These minor adjustments are made weekly. The ultimate goal of this sequential addition and selective grinding away of material is to reduce the size of the cleft gap and to have the two segments of alveolus contact with proper maxillary form. At this same appointment, an external retentive button is added at the site of the cleft. This retentive button helps seat the appliance and secure the retentive lip tapes and elastic bands (Figure 3). The taping of the cleft lip segments also serves to improve the alignment of the nasal base region by bringing the columella toward the midsagittal plane and improving the symmetry of the nose.

The infant is checked, and the appliance is modified every 7 to 10 days. When the cleft gap has been reduced to approximately 6 mm or less, a nasal stent is added, and active nasal cartilage molding begins. The nasal stent is a wire and acrylic projection that is placed inside the nasal dome on the cleft side of the nose. When properly placed and taped, blanching of the tissue overlying the tip of the nasal stent can be observed. The nasal stent also exerts a reciprocal intraoral molding force against the alveolar segments. The goal of the intraoral molding has the gingival tissues contact on either side of the alveolar ridge. Successful surgery can result even when a small cleft remains between the alveolar ridges.

At the conclusion of intraoral molding and nasal stenting, the alveolar segments should be aligned and the nasal cartilages, columella, and philtrum should be properly repositioned to facilitate the first surgical procedure. This first surgery is usually performed between 3 and 4 months of age. The infant wears the appliance continuously up to the time of surgery. Following surgical repair of the lip, the lip is taped, and no intraoral appliance is used. The palate repair, if indicated, is usually performed at approximately 11 to 13 months of age.

Cleft lip and palate patients pose special challenges for the treating dentist and require a team that involves several healthcare disciplines. An early coordinated team provides an accurate diagnosis, preventative and treatment regimens, ongoing evaluation and maintenance and can produce results that vastly improve the function, esthetics, and overall quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Wilson appreciates the skill and expertise of craniofacial and children’s reconstructive surgeons, Samuel Maurice, MD, and W. Dale Franks, DDS, MD. These individuals are dedicated to the health and well-being of children with craniofacial anomalies and seek to promote an optimal surgical outcome for these children.

References

- McNeil CK. Orthodontic procedures in the treatment of congenital cleft palate. Dent Rec. 1950;70(5):126-132.

- Mylin WK, Hagerty RF, Hess DA. Modern concepts in the treatment of unilateral cleft lip and palate. South Med J. 1969 Feb;62(2):171-174.

- Latham R. Orthodontic advancement of the cleft maxillary segment: a preliminary report. Cleft Palate J. 1980;17(3):227-233.

- Grayson BH, Santiago PE, Brecht LE, Cutting CB. Presurgical nasoalveolar molding in infants with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1999;36(6):486-498.

Thomas Wilson, DDS, is a graduate of the University of Iowa College of Dentistry. He completed his residency in pediatric dentistry at the University of Florida and his residency in orthodontics at Emory University. Dr. Wilson is board certified in both pediatric dentistry and orthodontics. He maintains a private practice in pediatric dentistry and orthodontics in Des Moines, Iowa. Dr. Wilson also holds an adjunct position at the University of Iowa College of Dentistry.

Thomas Wilson, DDS, is a graduate of the University of Iowa College of Dentistry. He completed his residency in pediatric dentistry at the University of Florida and his residency in orthodontics at Emory University. Dr. Wilson is board certified in both pediatric dentistry and orthodontics. He maintains a private practice in pediatric dentistry and orthodontics in Des Moines, Iowa. Dr. Wilson also holds an adjunct position at the University of Iowa College of Dentistry.