CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists discusses incorporating myofunctional therapy into orthodontic treatment planning to reduce post-orthodontic relapse.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz online to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Recognize the benefits of incorporating myofunctional therapy into orthodontic treatment planning.

- Recognize the role dentists can play in identifying and treating orofacial disorders treatable by myofunctional

- Identify orofacial disorders that benefit from myofunctional treatment options for long-term post-orthodontic retention.

- Realize myofunctional therapy’s potential to reduce post-orthodontic relapse and overall patient health.

Drs. Ryan Robinson and Carly Jacobs discuss how myofunctional therapy can help in treating the root cause of some complicated dentitions to minimize relapse

Introduction

The history of myofunctional therapy in conjunction with orthodontic treatment dates to as early as 1906 with the publication of American orthodontist Alfred Rodgers’ “Living Orthodontic Appliance.” Rodgers presumed that muscle alone would correct a malocclusion.1 To further this claim, Edward Angle theorized that “every malocclusion has a myofunctional cause.”2 Angle’s contribution to myofunctional therapy relied primarily on fixed orthodontic appliances (Figure 1). However, the myofunctional component of orthodontics with fixed appliances fell out of favor when relapse occurred in a high percentage of patients coupled with time-consuming techniques to achieve results. Hence, tooth-centered orthodontics with extractions or self-ligating brackets without the need for extractions grew in popularity (Figure 2). Nevertheless, post-orthodontic relapse was still problematic, requiring permanent retainers. As George Hahn once wrote in his publication “Retention — The Stepchild of Orthodontia,” Irrespective of the length of time a tooth is held in its new position … upon release, it will seek a place where it is in balance.”3 Myofunctional therapy has made significant strides in using specifically designed exercises to bring oral, facial, and cervical muscles into balance to reduce the need for permanent retainers.

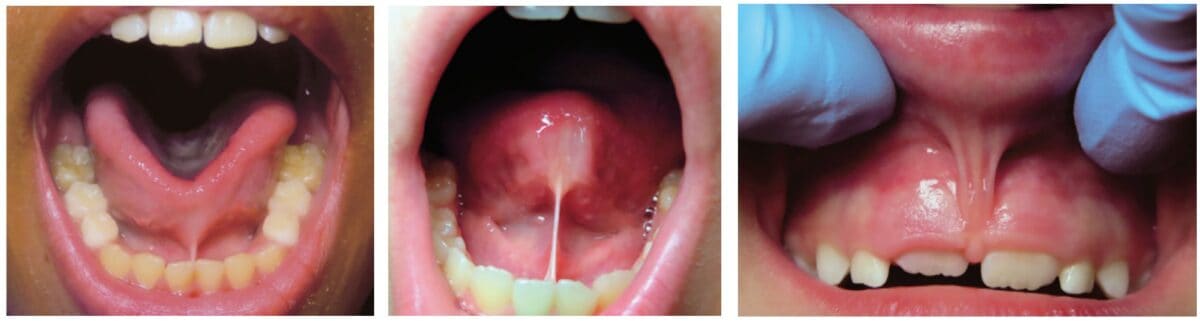

Myofunctional therapy (MFT) can be defined as exercising facial and cervical muscles to improve tone, function, and mobility, often referred to as neuromuscular re-education of muscle function.4 The scope of the exercises is designed to correct and maintain orofacial abnormalities such as mouth breathing, lip incompetence, tongue thrust habits, and parafunctional oral habits such as thumb sucking and bruxism, among others (Figures 3A-3C).5 These orofacial disorders increase the degree of difficulty in treating and retaining orthodontic conditions. Combining MFT with orthodontics produces stable maxillary arch development and resolves lower anterior crowding with little mechanical effort. In a systematic review of the effectiveness of myofunctional therapy with orthodontics conducted by Homem, et al., patients presenting with irregular movements of the tongue and malocclusions can be treated with both forms of treatment.6 The same study concluded that orofacial dyskinesis and anterior open bite treated with a combination of myofunctional therapy and orthodontics result in a more successful outcome for treatment and retention.6 An additional study concluded that closure of anterior open bite treated with a combination of MFT and orthodontics minimized relapse (0.48 mm-0.8 mm ortho and MFT; 1.3 mm-3.8 mm ortho only) (Figure 4).7 These studies and more represent ways MFT and orthodontics can be integrated to benefit the patient and provider through more successful treatment and retention of orthodontic abnormalities.

Identifying myofunctional abnormalities

Several types of dysfunctional areas of the oral cavity can be identified through pre-orthodontic treatment planning. As orthodontists, the qualifications and skills to determine the cause and treat orthodontic maladies are already established; thus, integrating MFT would be effortless. Typically, an evaluation of treatment options for the patient includes a combination of radiographs, dental impressions, and clinical observations. Adding diagnostic assessments of the oral, facial, and cervical muscles would identify areas in which post-orthodontic retention may be negatively affected. Myofunctional therapy can then be integrated into the treatment plan for a more comprehensive approach to treatment planning. However, using myofunctional therapy with the mechanical approach to minimize relapse has yet to be entirely accepted within the orthodontic community.

According to the American Dental Association, the primary justification for orthodontic treatment is malocclusion or teeth or jaw misalignment. The core issues that result in malocclusion or jaw misalignment are tongue thrust, narrow palate, bruxism, and lip incompetence, where myofunctional therapy can increase stability post-orthodontic treatment (Figure 5). The root cause of these abnormalities rests with the muscle tone of the tongue, mouth breathing, or tongue-tied situations (Figure 6). Evaluating these scenarios can seem obvious; however, there are unique cases that often are not completely evident. For instance, a tongue tie can create a speech impediment, mouth breathing habit, and/or a tongue thrust. Sounds that require the tongue to utilize the roof of the mouth, such as s, t, j, th, etc., or arch of the floor, such as r, c, etc., are difficult to pronounce.8 In addition, mouth breathing can lead to upper lip incompetence, narrow upper arch, retroposition of mandibular incisors, increased anterior face height, narrow (V-shaped maxillary arch), or expanded mandibular plane.9 Finally, a tongue thrust is among one the most difficult to treat and retain in orthodontics successfully. A tongue thrust identified by Dixit, et al., presents a” forward tongue posture, tongue thrust, during swallowing, contraction of the perio muscle, excessive buccinator hyperactivity, and swallowing without the momentary tooth contact normally required.”10 As a result, prolonged tongue thrust leads to open bites, high proclination of upper anterior teeth, high or narrow maxillary arch, and Class 11 Div. 1 Malocclusion (Figure 7).10,11 In addition, lisping or impaired speech has also been linked to tongue thrust. Myofunctional therapy would aid in treating the root cause of these particular abnormalities to minimize relapse.

Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy exercises

Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy (OMT) can include exercises to strengthen, reposition, and improve coordination of the mouth and throat muscles. Ideally, these exercises can achieve the optimal posture of lips, tongue, and teeth with the tongue resting on the roof of the mouth, the teeth touching or slightly apart, and the lips together without strain.4 The benefits of using these exercises that can minimize post-orthodontic relapse, as described by Dr. Krishana Acanta, include:

- Improving tongue elevation and tongue movement strength

- Correcting resting posture of the tongue, lips, and cheeks

- Improving tongue motility

- Improving maxillary constriction

- Improving sleep and breathing disorder patterns12

Exercises that improve the oral stability of the tongue, lips, and cheek muscles aid in preventing relapse (Figure 8). However, many challenges exist in incorporating OMT into the treatment phase of orthodontics. A few of them include the need for OMT training, the availability of a myofunctional therapist, and the shortage of time in a busy orthodontic practice. Ideally, an in-office myofunctional therapist or a referral to another certified myofunctional therapist for collaboration would make this transition easier, especially in complex cases. However, in less complicated cases, a few simple exercises taught in the office could benefit post-orthodontic retention. Incorporating OMT into pretreatment treatment planning, either with an MFT in-office or through collaboration outside of the office, would reduce some of these post retention challenges. Examples of OMT exercises compiled by Shah, et al., are as follows:

Lip Exercises

Lip closure and competency exercise: The child holds an ice cream stick between tightly closed lips for 5 seconds. Repeat 5-10 times.

Lip Puffing exercise: The child is asked to force air between lips and teeth, puffing out the lips as much as possible.

Lip movement: The child is asked to repeat the “OO-EE” sound.

Bubble-blowing exercise: The child blows bubbles through a toy with the help of the lips.

Tongue Exercises

Tongue clicks: The child places the tongue at the roof of the mouth, snapping it down.

Touch nose exercise: Protrude the tongue to touch the nose for 10 seconds. Repeat 10 times.

Touch chin: Protrude the tongue to touch the chin for 10 seconds. Repeat 10 times.

Touch sideward movement: Protrude the tongue and move from side to side, holding for 10 seconds. Repeat 10 times.

Teeth counting exercise: Count each tooth with the tongue.

Cheek Exercise

Roll tongue from side to side.

Fish face exercise: Puff the cheeks with air and blow a fish face. Repeat 10 times.

Yawning exercise: Yawning helps cheek and throat muscles. Repeat often throughout the day.

Jaw Exercises

Open the jaw wide and say AHH hold for 3-5 seconds.

Massage jaw gently toward and away from the lips.

Breathing Exercises

Balloon blowing: blow a balloon while breathing through the nasal cavity. Balloon blowing can also assist with lip competency.

Hold water in the mouth while breathing through the nasal cavity.13

One of the key factors in using myofunctional therapy is ensuring muscle compensation in other areas is not utilized. Therefore, treatment should be done routinely until the patient understands the correct technique, and then monitored for several weeks afterward until the patient demonstrates proper habituation of the right function.

Conclusion

It is essential to note that oral myofunctional therapy exercises alone are not intended to alter skeletal changes or move teeth but rather work as an integrated approach to comprehensive orthodontic treatment for a better long-term retention strategy. Therefore, assessing muscle dysfunctions included with standard orthodontic treatment planning would achieve better stability and retention results. Ideally, the earlier these dysfunctions can be identified in a patient’s life, the better the chances of positive results. However, it could also be considered in adult patients to minimize relapse post-orthodontics. As the orthodontic community realizes the benefits of myofunctional therapy on retention and overall patient satisfaction, it will soon become part of traditional orthodontic treatment planning.

The interest in myofunctional therapy is increasing. Read more about its role in treating sleep-breathing disorders. https://orthopracticeus.com/ce-articles/sleep-orthodontics-and-myofunctional-therapy/

References

- Rogers AP. Living orthodontic appliances. International Journal of Orthodontia, Oral Surgery and Radiography. 1929;15(1):1-14.

- Hawley CA. A removable retainer. International Journal of Orthodontia and Oral Surgery (1919). 1919;5(6):291-305.

- Hahn GW. Retention–The Stepchild of Orthodontia. The Angle Orthodontist. 1944;14(1):3-12.

- Swaroop AK. Oral Myofunctional Therapy: Breaking Detrimental Habits. Published https://www.icliniq.com/articles/dental-oral-health/oral-myofunctional-therapy. December 30, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023.

- Vollmer E. What is Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy. Therapy Works. https://therapyworks.com/blog/language-development/what-is-orofacial-myofunctional-therapy/. Published October 21, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023.

- Homem MA, Vieira-Andrade RG, Falci SG, Ramos-Jorge ML, Marques LS. Effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in orthodontic patients: a systematic review. Dental Press J Orthod. 2014 Jul-Aug;19(4):94-9. doi: 10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.094-099.oar.

- Smithpeter J, Covell D Jr. Relapse of anterior open bites treated with orthodontic appliances with and without orofacial myofunctional therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010 May;137(5):605-14.

- Reddy N, Marudhappan Y, Devi R, Narang S. Clipping the (tongue) tie. Journal Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18(3):395-398.

- Zhao Z, Zheng L, Huang X, Li C, Liu J, Hu Y. Effects of mouth breathing on facial skeletal development in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2021 Mar 10;21(1):108.

- Dixit UB, Shetty RM. Comparison of soft-tissue, dental, and skeletal characteristics in children with and without tongue thrusting habit. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013 Jan;4(1):2-6.

- Cayley AS, Tindall AP, Sampson WJ, Butcher AR. Electropalatographic and cephalometric assessment of tongue function in open bite and non-open bite subjects. Eur J Orthod. 2000 Oct;22(5):463-74.

- Mason R. Lip Incompetence. 2019. Orofacialmyology.com. https://orofacialmyology.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/orofacial-myologist-lip-incompetence.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2023

- Shah SS, Nankar MY, Bendgude VD, Shetty BR. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy in Tongue Thrust Habit: A Narrative Review. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2021 Mar-Apr;14(2):298-303.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Ryan P. Robinson, DDS, Delaware’s sole triple-boarded doctor in Craniofacial Pain and Dental Sleep Medicine, is dedicated to enhancing the overall health and well-being of his patients. Recognizing the significant impact of addressing the airway on patients’ health, he founded The Pain and Sleep Therapy Center. With extensive knowledge gained from over 1,000 hours of continuing education and mentorship by renowned airway clinicians, Dr. Robinson prioritizes identifying root causes instead of relying on temporary fixes. His passion extends to all age groups, as he helps adults improve their quality of life and children overcome lifelong issues. Beyond his profession, Dr. Robinson enjoys family time, travel, golf, and volunteering, including contributions to the blood cancer research department at Alfred I. DuPont/Nemours Hospital.

Ryan P. Robinson, DDS, Delaware’s sole triple-boarded doctor in Craniofacial Pain and Dental Sleep Medicine, is dedicated to enhancing the overall health and well-being of his patients. Recognizing the significant impact of addressing the airway on patients’ health, he founded The Pain and Sleep Therapy Center. With extensive knowledge gained from over 1,000 hours of continuing education and mentorship by renowned airway clinicians, Dr. Robinson prioritizes identifying root causes instead of relying on temporary fixes. His passion extends to all age groups, as he helps adults improve their quality of life and children overcome lifelong issues. Beyond his profession, Dr. Robinson enjoys family time, travel, golf, and volunteering, including contributions to the blood cancer research department at Alfred I. DuPont/Nemours Hospital. Carly M. Jacobs, DMD, a compassionate and dedicated dentist, found her true passion in dental sleep medicine after witnessing the transformative effects of treating sleep-related breathing issues. With extensive training and mentorship from top chronic pain and sleep providers worldwide, she takes pride in relieving facial pain, headaches, TMD, and airway obstructions. Driven by a patient-centric approach, she aims to find customized solutions for each individual, rejecting a one-size-fits-all model. Collaborating with Dr. Robinson, she expands the reach of The Pain and Sleep Therapy Center, focusing on patients in the Main Line and greater Philadelphia, Pennsylvania region. Beyond dentistry, Dr. Jacobs enjoys traveling, cooking, tennis, and Broadway shows.

Carly M. Jacobs, DMD, a compassionate and dedicated dentist, found her true passion in dental sleep medicine after witnessing the transformative effects of treating sleep-related breathing issues. With extensive training and mentorship from top chronic pain and sleep providers worldwide, she takes pride in relieving facial pain, headaches, TMD, and airway obstructions. Driven by a patient-centric approach, she aims to find customized solutions for each individual, rejecting a one-size-fits-all model. Collaborating with Dr. Robinson, she expands the reach of The Pain and Sleep Therapy Center, focusing on patients in the Main Line and greater Philadelphia, Pennsylvania region. Beyond dentistry, Dr. Jacobs enjoys traveling, cooking, tennis, and Broadway shows.