CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to provide historical background and current clinical information on the importance of lip closure to health and esthetics.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz online to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize some history regarding the relationships of lip closure to various functions such as breathing, eating, and communicating.

- Realize how mouth breathing can have negative consequences on areas such as the bite, the face, and the airway.

- Identify some health conditions that may be associated with open mouth posture.

- Observe treatment of a patient who had a long history of pain and dysfunction due to lip incompetence issues.

Dr. Michael Gunson looks to the past and present for a view of the effects of ineffective lip closure issues

Biology, medicine, environmental studies, behavioral sciences, and more have improved with the application of principles from Systems Thinking. The face is obviously a complex system. The first step in Systems Thinking is to define the boundaries of the system and to explain its purpose.

“All systems seek to achieve a purpose. Whether human-made or natural, all systems strive to do something. Systems Thinking…demands determination and consideration of the purpose – it is PURPOSE ORIENTED.”2

According to Systems Thinking then, a clinician can only be successful in treating the face if they can answer the question: “What is the purpose of the face?”

The purposes of the face, in hierarchal order, are 1) breathing, 2) eating, and 3) communicating. The brain prioritizes these purposes by causing all parts of the facial system to work together towards the three goals. When growth is inappropriate, the brain compensates to accomplish the purposes of the face often at the expense of the parts (fascia, muscles, teeth, joints, spine, etc.) These compensations may cause dysfunction, deformation, and destruction (Figures 1-4). Knowing the purposes of the face allows us to define the healthiest place for each individual part of the face. It is that position that minimizes energy expenditure as that part engages and relates with other parts in helping the face to breathe, eat, and communicate.

One of the most important part relationships in function is lip closure. The lips must close to achieve the following: 1) facilitate nasal breathing when awake and asleep, 2) coordinate chewing and swallowing, and 3) provide for clear and correct communication with speech and facial expression. As stated above, the parts of the face must work with the least amount of energy use; in this case, the lips must close passively at rest and in function. When the lips are far from each other, the brain still insists that the lips close to breathe, eat, and communicate, but the work to close in this scenario becomes detrimental.3 Repetitive energetic movements in turn damages the parts of the facial system.

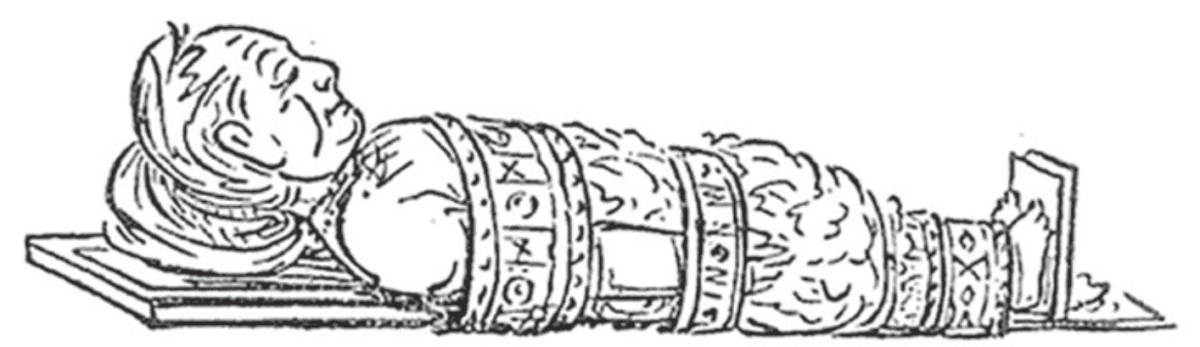

In the 1870s, a painter/explorer George Catlin observed how integral lip closure is to the entire body. Catlin traveled extensively across North and South America, visiting and painting the Native American people. After several years of close interaction, he observed that the indigenous American population was healthier than their European counterparts. Their superior health, he concluded, could be traced to the simple act of keeping their mouths closed. He published a book with art sketches called Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life.4 In his book, Catlin showed that mouth breathing had negative consequences in three areas: the bite, the face, and the airway.

The Bite

Catlin made the connection between lip closure and the healthy eruption of teeth into occlusion:

An Indian child is not allowed to sleep with its mouth open, from the very first sleep of its existence; the consequence of which is, that while the teeth are forming and making their first appearance, they meet (and constantly feel) each other; and taking their relative natural positions, form that healthful and pleasing regularity which has secured to the American Indians, as a Race, perhaps the most manly and beautiful mouths in the World.5 (Figures 5-6)

Burstone agrees, writing that there is a “role of lip posture as an etiologic factor in the formation of a malocclusion” and that orthodontic treatment “may not be stable if the interlabial gap is large.”6 This is shown well by Op Heij in his work regarding anterior implant placement adjacent to natural teeth. He noted an “increased vertical movement of the natural dentition” adjacent to dental implants especially in the long-faced patient.7

Malocclusion is associated with mouth breathing.8-11 In a large meta-analysis, downward-backward growth of the maxillofacial complex with narrow maxillas and dental crossbites were noted in mouth-breathing children.12,13 It is possible that repetitive application of force via lip closure causes lingual inclination of the anterior dentition. Yomo Ohno showed an association of lip forces, lingual inclination of the anterior teeth, and arch misalignment.14

The Face

Catlin describes a pretty girl who had passive lip closure:

I recollect, and never shall forget while I live, that in my boyhood I fell in love with a charming little girl, merely because her pretty mouth was always shut; her words, which were few, and always (I thought) so fitly spoken, seemed to issue from the centre of her cherry lips, whilst the corner of her mouth seemed (to me) to be honeyed together.15

Catlin’s obvious esthetic appreciation of the girl’s lip function is telling. In contrast, Catlin presents the pitiful portrait of a woman with lip incompetence:

I knew a young lady many years ago, amiable and intelligent, and agreeable in everything excepting the unfortunate derangement and shapes of her teeth; the front ones of which, in the upper jaw, protruding half an inch or more forward of the lower ones, and quite incapable of being covered by the lip, for which there was a constant effort; the result of which was a most pitiable expression of the mouth and consequently of the whole face, with continual embarrassment and unhappiness of the young Lady, and sympathy of her friends.16 (Figure 7)

Dr. Ricketts concurs stating that lip incompetence “frequently results in a very unpleasant appearance of the lips and the illusion of a weak chin, and it actually is a source of embarrassment to many patients.”17 Changes in facial development start early in mouth breathers with long faces and narrow noses.18

If the lips are separated in the anteroposterior or vertical dimension, then there is muscle strain to close in function. Increasing VDO increases lower face height and lip strain with resultant facial esthetic decline.19 Ghorbanyjavadpour also showed that smaller interlabial gaps are considered more attractive. Interlabial gap causes premature aging with increasing wrinkles, deepening folds, and longer, flatter lips.21-23 (Figures 8-10)

This strain has negative facial consequences even in children. Inada wrote that interlabial gap “may induce a negative vicious cycle in the growth of the maxillofacial area, with detrimental effects on the rest of the body.”24

Treatments focused on decreasing interlabial gap reduce muscle strain and improve facial esthetics.25-27 (Figure 11)

Lip incompetence is not only associated with unhealthy facial development but it also affects the neck with related spinal curvatures such as kyphosis, lordosis, as well as pelvic tilt28,29 (Figure 12). A study showed that correction of mouth breathing and posture rehabilitation may correct early abnormalities.30

The Airway

Catlin:

…the nostrils, with their delicate and fibrous linings for purifying and warming the air in its passage, have been mysteriously constructed, and measure the air and equalize its draughts during the hours of repose.31

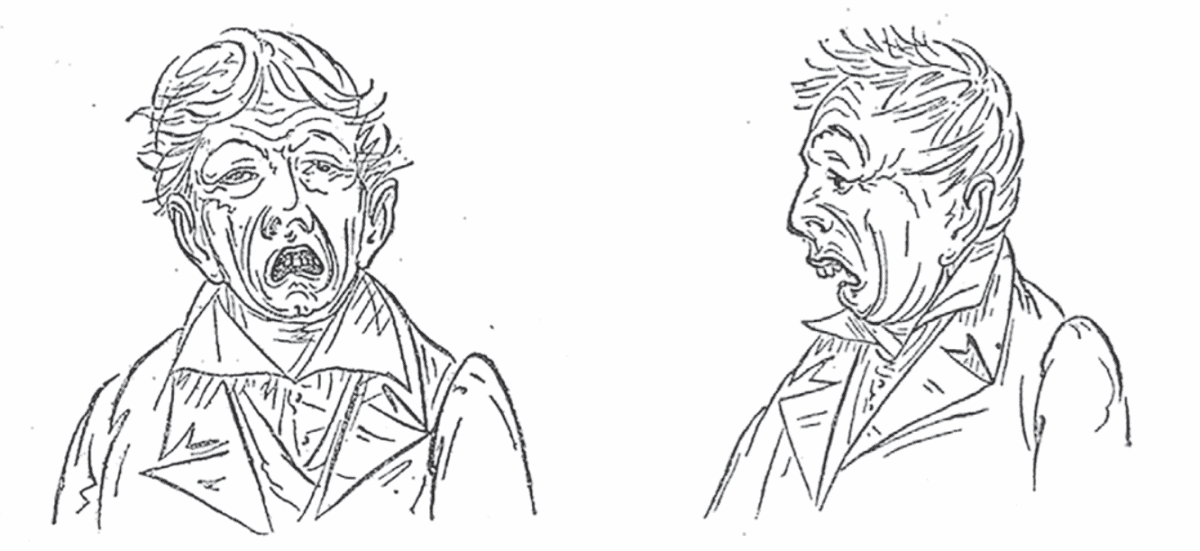

There is no perfect sleep of man or brute with the mouth open; it is unnatural, and a strain upon the lungs which expression of the countenance and the nervous excitement plainly show.32 (Figures 13-14)

As a society, we recognize the pathology of mouth breathing as seen in the use of the term “mouth-breather” as a pejorative reference to someone’s intelligence or health.33 The following is a quote from a medical journal in 1892:

From the condition of a “mouth-breather,” it is but a short step to one of two results more often both: deafness, and that peculiarly stupid, sleepy, inane, foolish expression of countenance so characteristic of the “mouth-breather.”34

Science has published much about the airway pathology of those with lip incompetence. Nasal congestion has been observed in mouth breathers since the late1800s.35 Allergic rhinitis and asthma seem also to be associated with open mouth posture.36 More recently, sleep disordered breathing and obstructive sleep apnea are more prevalent in children with interlabial gap, mentalis strain, and/or mouth breathing.37,38

Clinical example

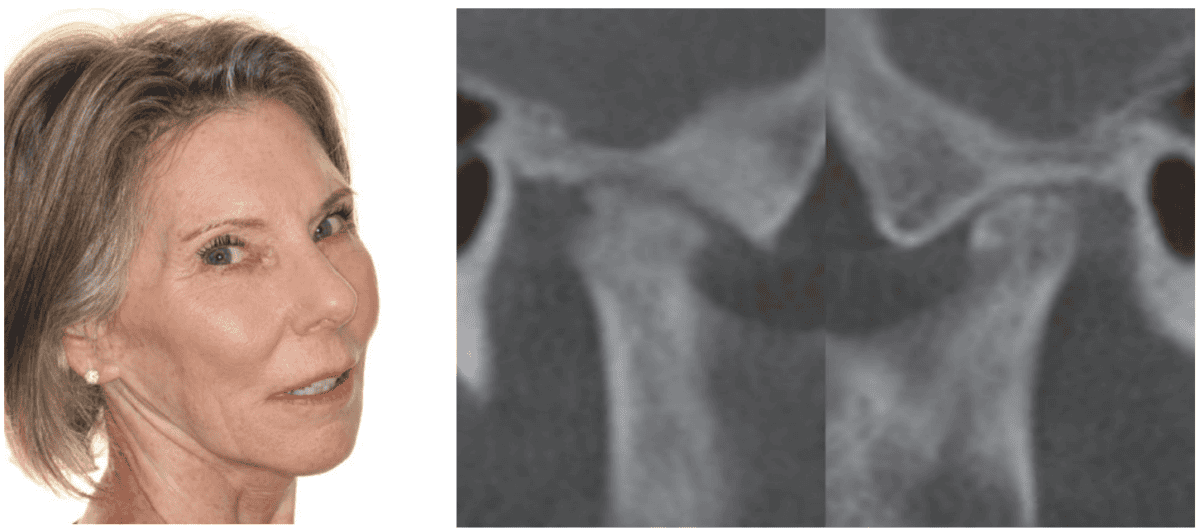

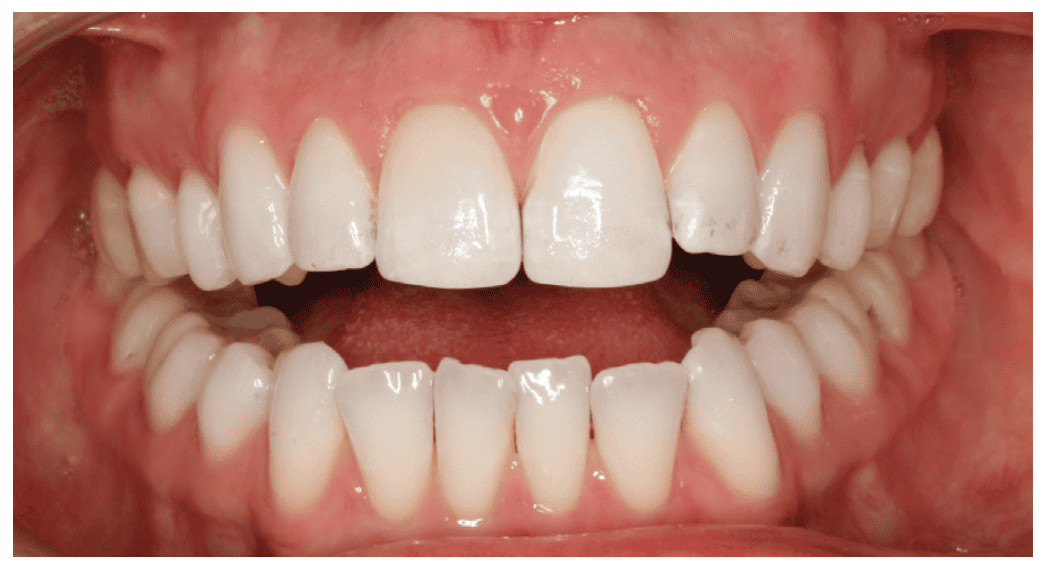

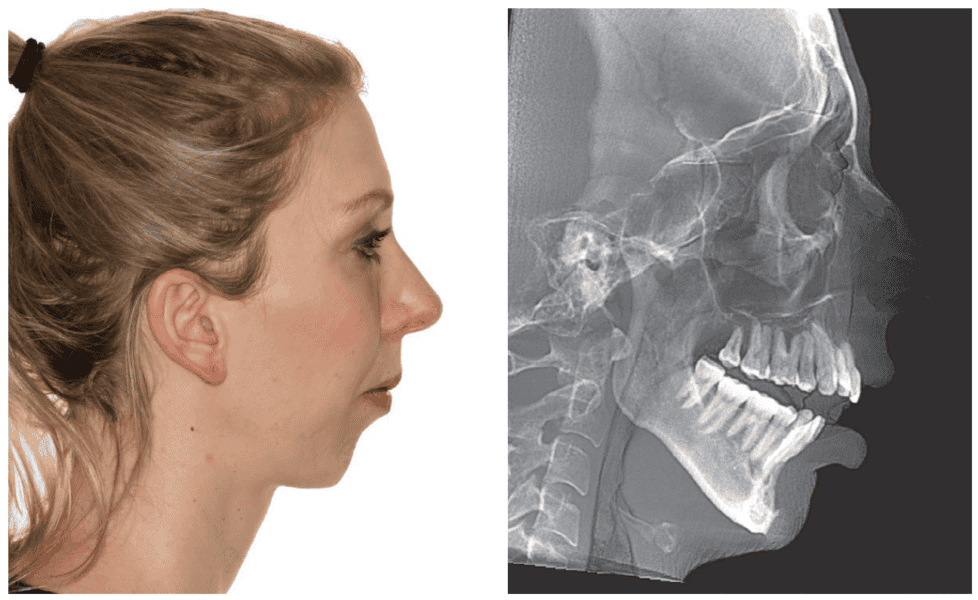

A 39-year-old female with a significant open bite presents to the oral and maxillofacial surgeon’s office on referral from the orthodontist for orthognathic surgery. She has a long history of pain and dysfunction. (Figures 15-17)

Her list of complaints include the following:

- Anterior open bite

- Difficulty with lip closure — food falls out of mouth

- Muscles of mastication pain

- TMJ capsular pain

- Limited diet — soft food

- Masseter muscle spasms with tooth chatter

- Lisp

- Morning fatigue with mental cloudiness

- Exercise intolerance

- Extreme pain lower anterior teeth

- Joint noises

- Jaw posturing for comfort

She states:

“I have spent my whole life never feeling relaxed in my face because my mouth has never touched, my mouth was always open, and all the muscles would be pulling, and I could never feel relaxed.”39

Prior treatments have included

- Orthodontics — post treatment opening of anterior bite

- Dental splints x 2 — no improvement with first, worsening symptoms with second

- Physical therapy twice a week — improvement

- Anti-inflammatories — mild improvement

- Acupuncture — no effect

She was offered but refused:

- Open TMJ surgery

- Hydrocortisone TMJ injections

- Additional orthodontic treatment

- Anxiety and depression medications

- Full-mouth prosthodontic reconstruction

- Facial TENS and TMJ prolotherapy

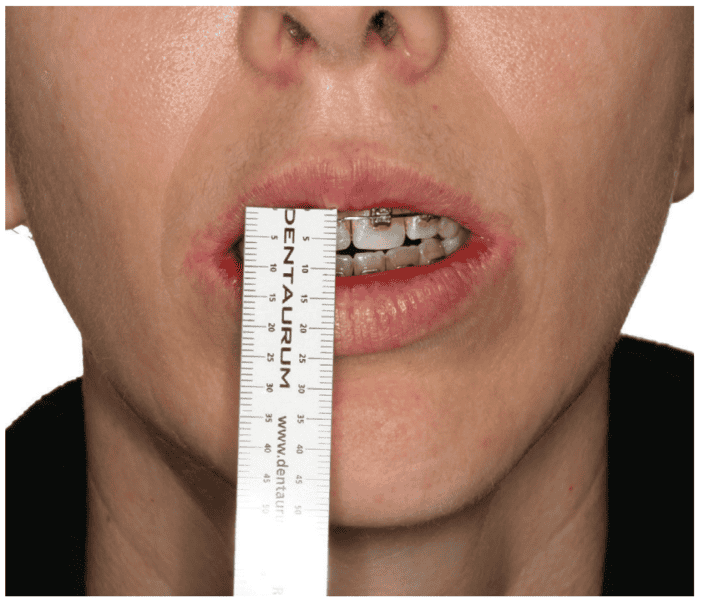

Her exam revealed:

- Interlabial gap of 14 mm

- Anterior open bite of 4 mm

- Maxillary and mandibular retrusion

- Anterior maxillary excess

- Long chin length

- Erupted third molars in occlusion

If we are to believe that her symptoms are related to her compensations, her efforts to breathe, eat, and communicate, then our goals ought to be to facilitate those actions. Her lips need to come closer together, and the teeth need to function more appropriately.

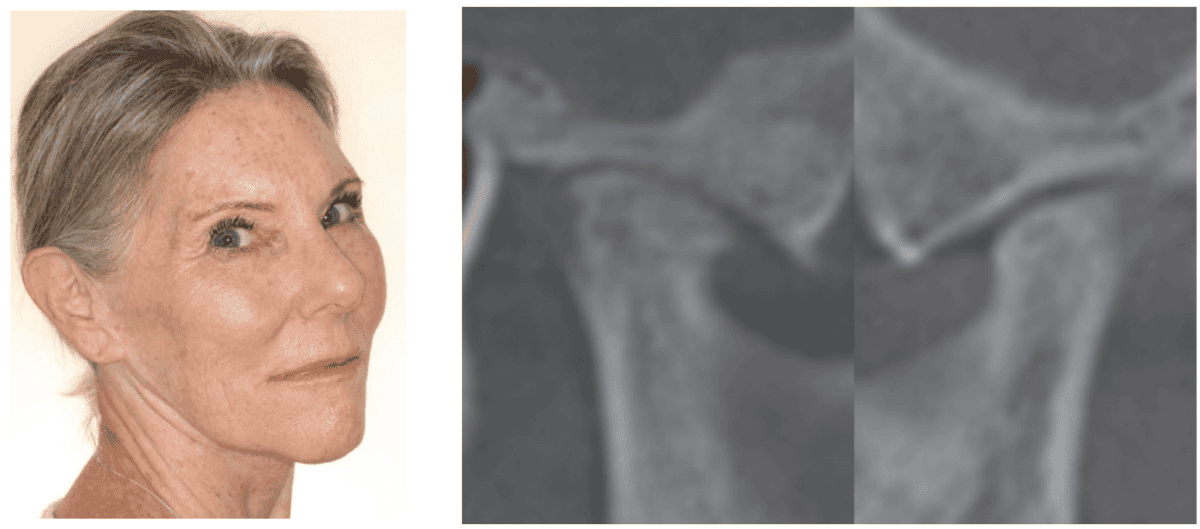

The first step to close her lips was to remove the 3rd molars which allowed over 3 mm of anterior closure. Immediately following extractions, she reports increased exercise tolerance and elimination of her lisp. She comments: “Two weeks post-op, I ran 4 miles straight without stopping once. I no longer felt 9 months pregnant. I now wake up every morning refreshed. I wake up now without an alarm clock and feel wonderful.”

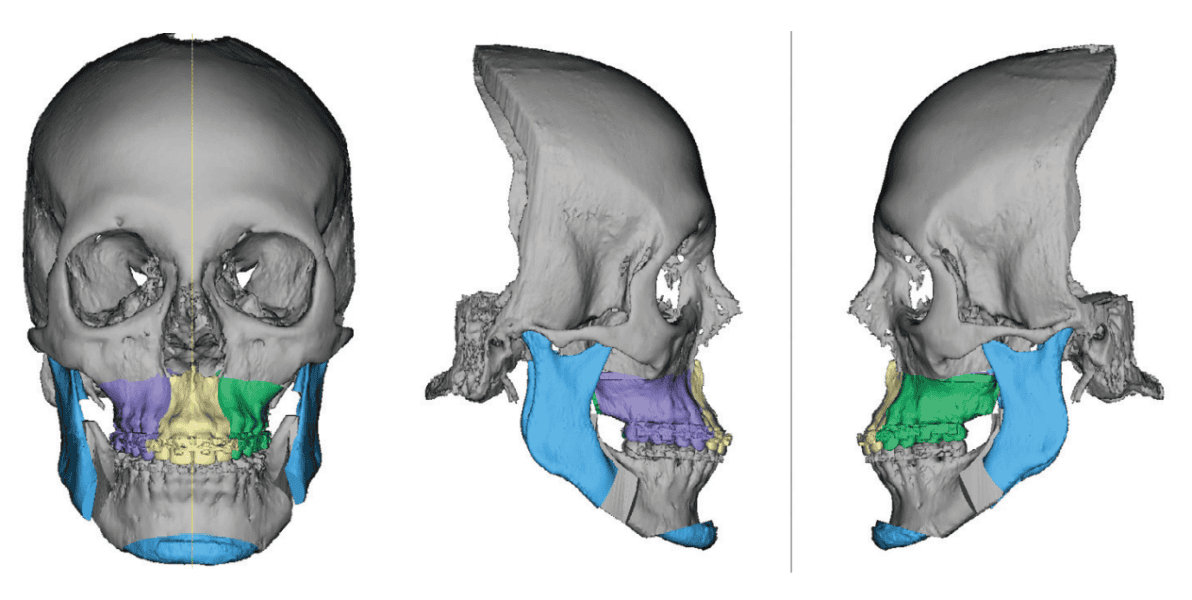

Because she still had 11 mm of interlabial gap, she required orthognathic surgery (Figure 18). The surgery was planned with the intent of closing her lip incompetence. The maxilla was impacted 4 mm, the open bite was closed by 4 mm, the chin was shortened by 2 mm, and the whole complex was counterclockwise rotated. Virtual surgical planning allows us to track the amount of vertical reduction in the anterior to assure correction of lip incompetence (Figures 19-20).

After surgery, she reported complete cessation of muscle spasticity, headaches, and jaw posturing. She said:

“Right out of surgery, the first time I felt my lips touch was one of the most emotional experiences because I never felt something so nurturing before…I’ve never had that feeling before in my life, and to get it for the first time was remarkable and to feel at peace.”40 (Figures 21-22)

Conclusions

After reviewing the literature about the deleterious effects of lip incompetence on the facial health of patients, it ought to be in the forefront of every clinician’s treatment plan to assist patients in getting their lips together. Dentists can reduce vertical dimension through occlusal equilibration. Orthodontists can close anterior open bites by managing transverse discrepancies and with posterior intrusion mechanics. Thin lips can be enlarged carefully by cosmetic surgeons with fat or dermal fillers. And orthognathic surgery can effectively treat excessive anterior vertical heights by impacting the anterior maxilla, closing open bites, and reducing chin lengths. The relief that patients feel when correcting lip incompetence is dramatic as we are literally “shutting our patients mouths to save their lives.”

After reading about lip closure, check out a related topic — “Rapid, nonsurgical open-bite closure with a passive self-ligating bracket system using a differential bonding technique” by Drs. Michael Choy and John Burnheimer at https://orthopracticeus.com/case-studies/rapid-nonsurgical-open-bite-closure-passive-self-ligating-bracket-system-using-differential-bonding-technique/.

References

- Burge S. System Purpose. 2015. https://www.burgehugheswalsh.co.uk/Uploaded/1/Documents/System-Purpose.pdf (Accessed March 8, 2024).

- Schlossberg, L, Harris, S. An electromyographic investigation of the functioning perioral and suprahyoid musculature in normal occlusion and Class II, Division 1 dysplasia cases. Am J Orthod. February 1956; 42(2):153.

- Catlin G. Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life. Pantianos Classics. Reprint adapted from revised edition 1890.

- Ibid, 46.

- Burstone CJ. Lip posture and its significance in treatment planning. Am J Orthod. 1967 Apr;53(4):262-284.

- Op Heij DG, Opdebeeck H, van Steenberghe D, Quirynen M. Age as compromising factor for implant insertion. Periodontol 2000. 2003;33:172-184.

- Mattar SE, Anselmo-Lima WT, Valera FC, Matsumoto MA. Skeletal and occlusal characteristics in mouth-breathing pre-school children. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004 Summer;28(4):315-318.

- Granja GL, Leal TR, Lima LCM, Silva SED, Neves ÉTB, Ferreira FM, Granville-Garcia AF. Predictors associated with malocclusion in children with and without sleep disorders: a cross-sectional study. Braz Oral Res. 2023 Oct 27;37:e106.

- Ma Y, Xie L, Wu W. The effects of adenoid hypertrophy and oral breathing on maxillofacial development: a review of the literature. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2024 Jan;48(1):1-6.

- Otsugu M, Sasaki Y, Mikasa Y, Kadono M, Sasaki H, Kato T, Nakano K. Incompetent lip seal and nail biting as risk factors for malocclusion in Japanese preschool children aged 3-6 years. BMC Pediatr. 2023 Oct 26;23(1):532.

- Zhao Z, Zheng L, Huang X, Li C, Liu J, Hu Y. Effects of mouth breathing on facial skeletal development in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2021 Mar 10;21(1):108

- Souki BQ, Pimenta GB, Souki MQ, Franco LP, Becker HM, Pinto JA. Prevalence of malocclusion among mouth breathing children: do expectations meet reality? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009 May;73(5):767-773.

- Ohno Y, Fujita Y, Ohno K, Maki K. Relationship between oral function and mandibular anterior crowding in early mixed dentition. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2020 Oct;6(5):529-536.

- Catlin, 75.

- 79.

- Ricketts RM. Esthetics, environment, and the law of lip relation. Am J Orthod. 1968 Apr;54(4):272-289.

- Al Ali A, Richmond S, Popat H, Playle R, Pickles T, Zhurov AI, Marshall D, Rosin PL, Henderson J, Bonuck K. The influence of snoring, mouth breathing and apnoea on facial morphology in late childhood: a three-dimensional study. BMJ Open. 2015 Sep 8;5(9):e009027.

- Sun J, Lin YC, Lee JD, Lee SJ. Effect of increasing occlusal vertical dimension on lower facial form and perceived facial esthetics: A digital evaluation. J Prosthet Dent. 2021 Oct;126(4):546-552.

- Ghorbanyjavadpour F, Rakhshan V. Factors associated with the beauty of soft-tissue profile. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2019 Jun;155(6):832-843.

- Oliveira AC, Dos Anjos CA, Silva EH, Menezes Pde L. Aspectos indicativos de envelhecimento facial precoce em respiradores orais adultos [Indicative factors of early facial aging in mouth breathing adults]. Pro Fono. 2007 Jul-Sep;19(3):305-312.

- Demir R, Baysal A. Three-dimensional evaluation of smile characteristics in subjects with increased vertical facial dimensions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020 Jun;157(6):773-782

- Qadeer TA, Jawaid M, Fahim MF, Habib M, Khan EB. Effect of lip thickness and competency on soft-tissue changes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022 Oct;162(4): 483-490.

- Inada E, Saitoh I, Kaihara Y, Murakami D, Nogami Y, Kubota N, Shirazawa Y, Ishitani N, Oku T, Yamasaki Y. Incompetent lip seal affects the form of facial soft tissue in preschool children. 2021 Sep;39(5):405-411.

- Yogosawa F. Predicting soft tissue profile changes concurrent with orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 1990 Fall;60(3):199-206.

- Yu YH, Kim YJ, Lee DY, Lim YK. The predictability of dentoskeletal factors for soft-tissue chin strain during lip closure. Korean J Orthod. 2013 Dec;43(6):279-287.

- Zide BM, McCarthy J. The mentalis muscle: an essential component of chin and lower lip position. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989 Mar;83(3):413-420.

- Milanesi JM, Borin G, Corrêa EC, da Silva AM, Bortoluzzi DC, Souza JA. Impact of the mouth breathing occurred during childhood in the adult age: biophotogrammetric postural analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011 Aug;75(8):999-1004.

- Yi LC, Jardim JR, Inoue DP, Pignatari SS. The relationship between excursion of the diaphragm and curvatures of the spinal column in mouth breathing children. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2008 Mar-Apr;84(2):171-177.

- Corrêa EC, Bérzin F. Efficacy of physical therapy on cervical muscle activity and on body posture in school-age mouth breathing children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Oct;71(10):1527-1535.

- Catlin, 30.

- 27.

- Oxford English Dictionary. Mouth-Breather. https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=mouth+breather. (Accessed March 8, 2024).

- Fanning, AM. Deafness and the care of the ears. The Popular Science Monthly, December 1892:212.

- Cassells JP. “Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life:” Being Remarks on Mouth-Breathing, and Some of Its Consequences, Especially to the Apparatus of Hearing: A Contribution to the Ætiology of Ear-Disease. Edinb Med J. 1877 Feb;22(8):728-741.

- Georgalas C, Terreehorst I, Fokkens W. Current management of allergic rhinitis in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010 Feb;21(1 Pt 2):e119-126.

- Oh JS, Zaghi S, Peterson C, Law CS, Silva D, Yoon AJ. Determinants of Sleep-Disordered Breathing During the Mixed Dentition: Development of a Functional Airway Evaluation Screening Tool (FAIREST-6). Pediatr Dent. 2021 Jul 15;43(4):262-272.

- Fitzpatrick MF, McLean H, Urton AM, Tan A, O’Donnell D, Driver HS. Effect of nasal or oral breathing route on upper airway resistance during sleep. Eur Respir J. 2003 Nov;22(5):827-832.

- Interview conducted by Dr Alan Marcus May 22, 2018.

- Ibid

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Michael Gunson, DDS, MD, operates an oral and maxillofacial surgery private practice, limited to orthognathic surgery, in Santa Barbara, California.

Michael Gunson, DDS, MD, operates an oral and maxillofacial surgery private practice, limited to orthognathic surgery, in Santa Barbara, California.