CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to educate readers on the implications of poor nasal breathing with maxillary hypoplasia on wellness and the importance of addressing sleep-disordered breathing through the DOME approach.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz online to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Define different types of sleep-disordered breathing.

- Identify anatomy that affects nasal breathing.

- Identify the DOME approach to treating nasal obstruction.

- Observe patient outcomes after being treated with the DOME approach.

Drs. Claudia Pinter and Stanley Liu illustrate a protocol to improve nasal breathing in orthodontic care

Bestselling author James Nestor highlights in his book, Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art that nasal breathing has profound effects on overall health, including respiratory function, cardiovascular health, mental clarity, sleep quality, and athletic performance. Of all the contributors to overall wellness, a healthy way to breathe has eluded attention from modern medicine and dentistry. This is especially true with breathing during sleep.

Breathing interruptions during sleep make up a constellation of conditions called “sleep-disordered breathing,” (SDB) with common diagnoses including snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea. A contemporary population-based study on adults estimates SDB to be present in 23.4% of women, and 49.7% of men. SDB is independently associated with hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and depression.1

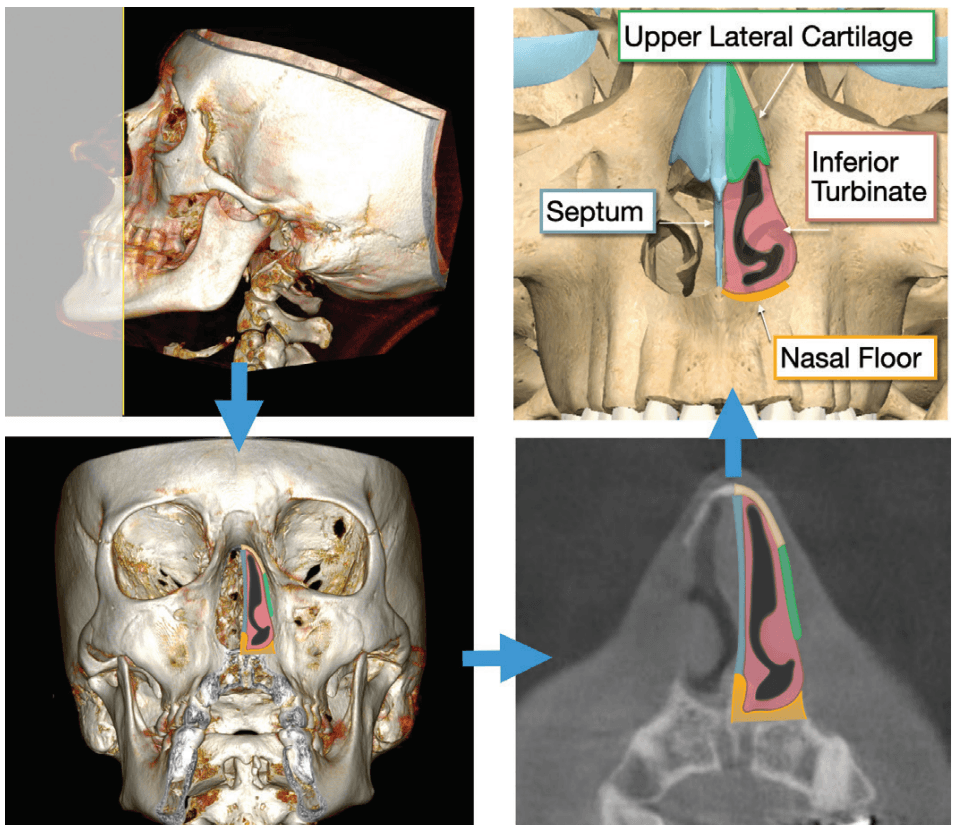

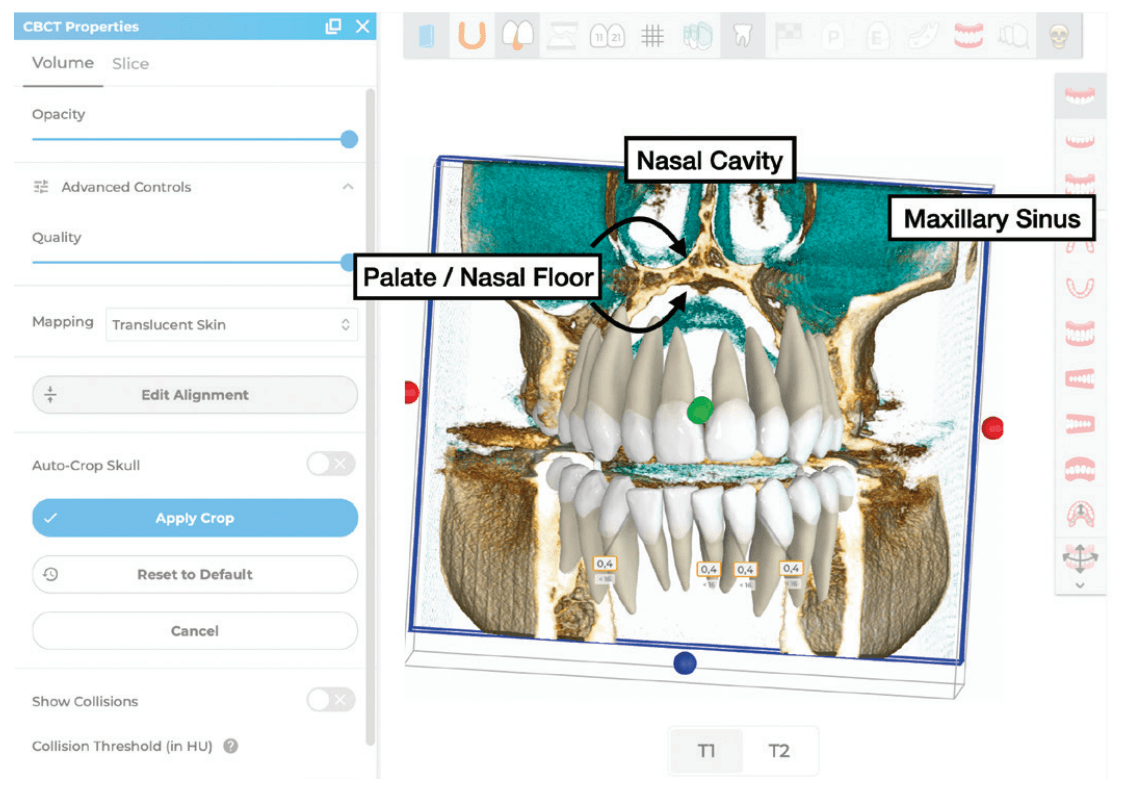

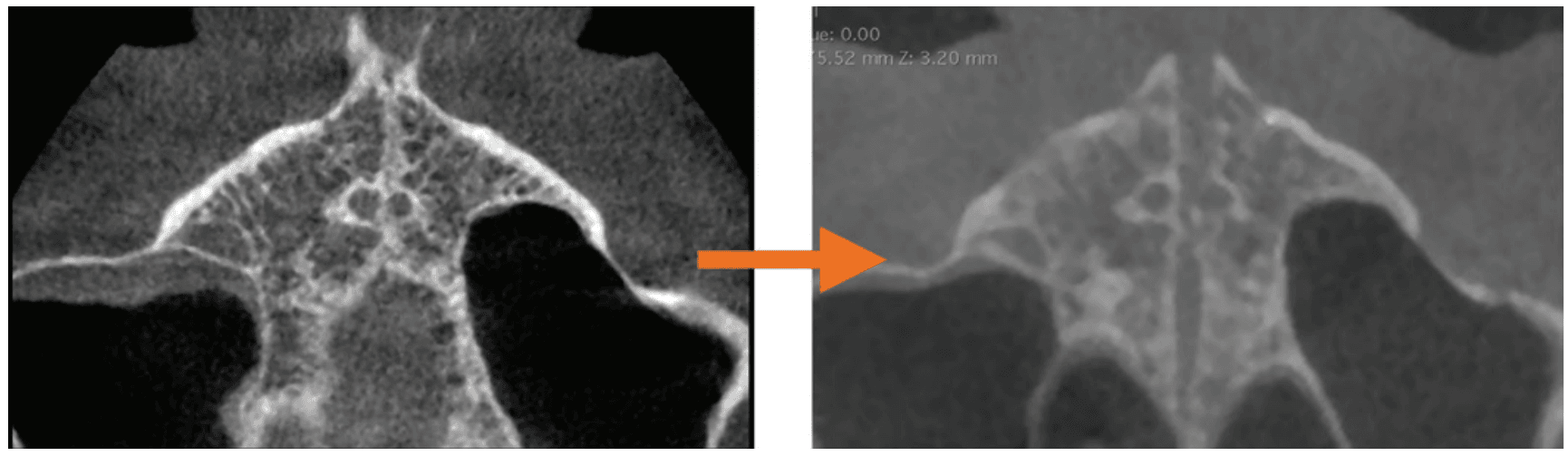

Regarding nasal breathing, the internal nasal valve (INV) is the narrowest part of the nasal cavity and is the location of greatest airflow resistance.2,3 Located about 1.3 cm posterior to the nostril opening, it is surrounded by the dorsal septum medially, the head of inferior turbinate laterally, upper lateral cartilages superiorly, and the maxillary roof (nasal floor) inferiorly. Anatomic causes of nasal obstruction frequently involve structures of the INV. Beyond anatomy, there are physiologic and pathophysiologic causes of nasal obstruction (Figure 1).

When it comes to anatomic treatment, surgical approaches to the septum, inferior turbinate, and upper lateral cartilage of the INV are well described. What has been less discussed until recently is maxillary expansion at the nasal floor.4 This is likely a byproduct of otolaryngologists (ear, nose, throat surgeons) focusing on structures treated within their scope. Historically though, otolaryngologists have collaborated with orthodontists to treat nasal obstruction via maxillary expansion.5

In 2017, Dr. Ryan Williams and Dr. Stanley Liu at Stanford Otolaryngology performed a retrospective case-control study to identify phenotypes of patients who complain of persistent nasal obstruction after surgery.6 Eighty-nine subjects with perioperative validated questionnaires and computed tomography imaging were included. The study showed that patients with persistent nasal obstruction after intranasal surgery (septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction) presented with a narrower maxilla (and nasal floor), near the region of the internal nasal valve.

In parallel, Dr. Christian Guilleminault mentored Dr. Audrey Yoon and Dr. Stanley Liu at Stanford Sleep Medicine to apply maxillary expansion techniques for SDB patients. From around 2015, Dr. Stanley Liu described the change as converting a high-arched palate to a “dome”-shaped palate. As the surgical-orthodontic techniques progressed, “dome” became an acronym of “maxillary expansion” with “distraction osteogenesis.” This shifted maxillary expansion from a dentoalveolar-first to a nasal-floor first process, and as an approach rather than specific surgical or dental techniques.

Subsequent studies were undertaken to understand the mechanism of action of DOME using treatment-specific rhinomanometry and patient-specific computational fluid dynamics analysis. With expansion at the INV region, nasal airflow slows significantly, and the downstream negative pressure that collapses the pharyngeal airway decreases.7 DOME for both the adult and pediatric populations had similar outcomes, most notably a patient-reported decrease in nasal obstruction.8-10 The decrease in apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was associated with increase of INV surface area and angle.8,11

For patients requiring surgical osteotomies, endoscopic approaches to DOME were introduced.12 Finally, to complete the full circle dating back to Williams and Liu’s original study, patients who underwent DOME after nasal surgery were examined. The study found that a transverse increase of at least 6 mm at the INV was associated with resolution of nasal obstruction and improvement of sleep-related symptoms.13 Since then, many colleagues in the field of SDB across different disciplines have continued to expand (puns intended) upon DOME.14,15

Today, the need of invasive maxillary osteotomy to expand the adult maxilla has become markedly reduced. The advent of custom, temporary anchorage device supported expanders have increased the phenotype of eligible patients for non-surgical expansion. Moreover, restoration of cosmesis and occlusion evolved rapidly. European leaders including Dr. Christian Leonardt and Dr. Claudia Pinter have further streamlined the DOME approach to a dentist-friendly ecosystem. In this article, the contemporary DOME approach for dentists is highlighted.

Case report No. 1

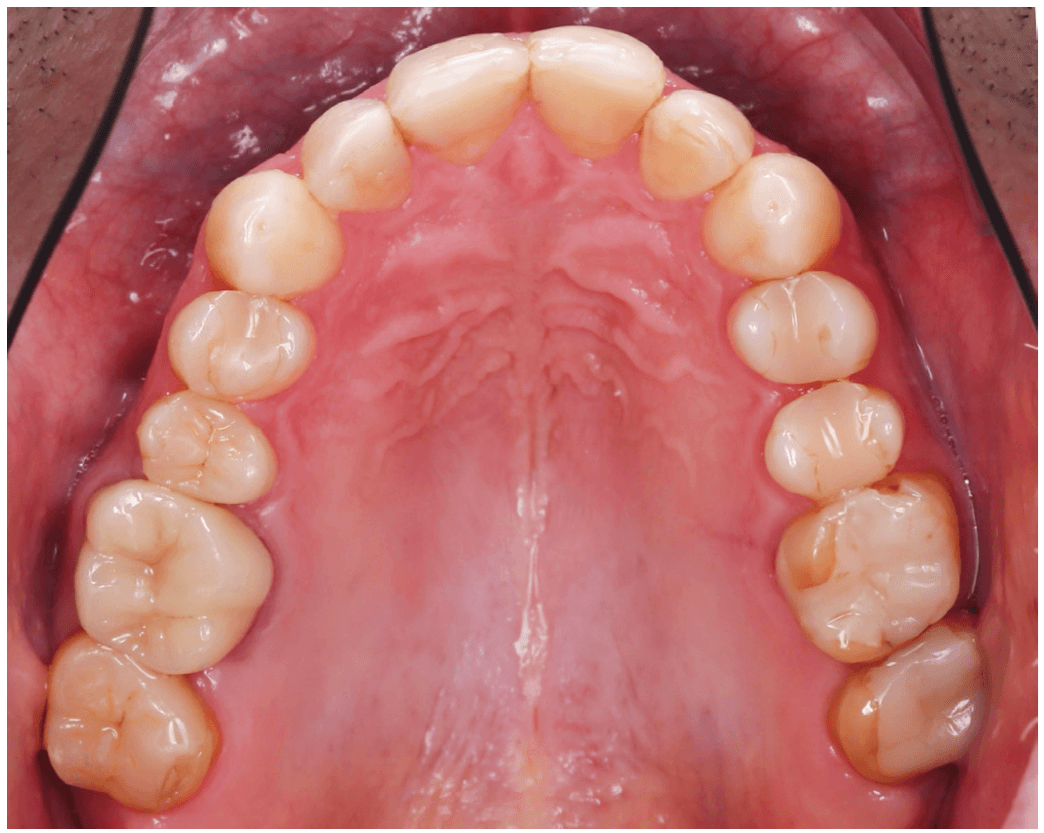

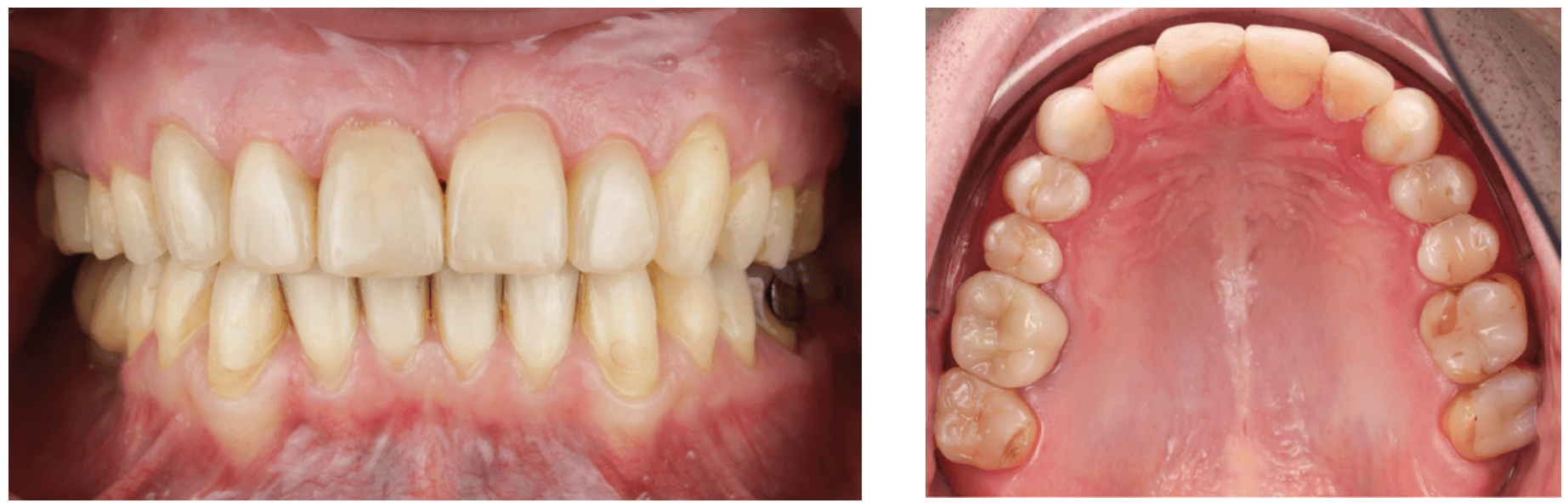

A 51-year-old male was referred by the treating dentist to address malocclusion before doing extensive restorative work. The patient presented equal facial thirds and pronounced buccal corridors. Intraorally, the teeth presented in Class I, with an anterior open bite, a narrow upper jaw, and a high-arched palate.

In cases with maxillary deficiency, the narrowing of the nasal cavity increases airflow resistance, potentially leading to nasal obstruction snoring and resulting in sleep breathing disturbances.

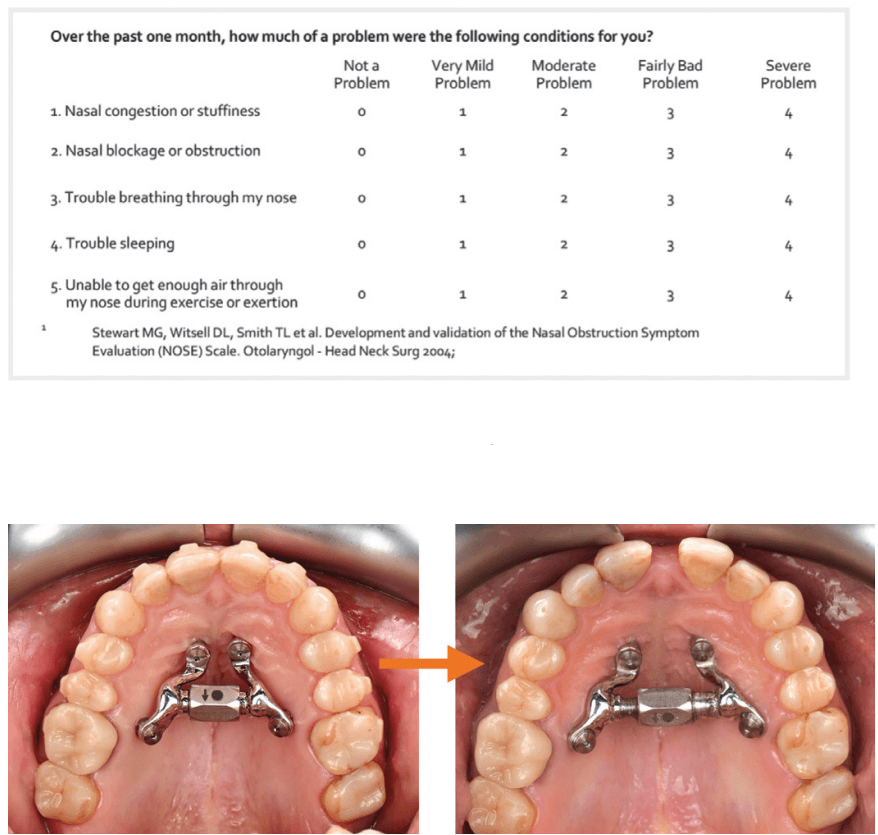

Upon investigation, the NOSE Score indicated nasal obstruction, and the patient reported frequent and loud snoring.

Insufficient lateral overjet could have been addressed with dental expansion of the upper arch, which would not have effects on the nasal cavity.

The patient opted for a DOME (Distraction Osteogenesis Maxillary Expansion) approach to address malocclusion, create more space for the tongue, and to facilitate nasal breathing both during wakefulness and sleep.

To ensure predictable suture separation of the maxillary halves, minimally invasive osteotomies were performed (Periodontist: Dr. Christian Leonhardt). During the same appointment, four mini-screws were placed: two in the anterior palate (Benefit PSM Medical, 2 mm x 11 mm) and two between the roots of the second premolar and first molar (Benefit PSM Medical, 2 mm x 13 mm). Surgical guides were used to place the mini-screw in areas with sufficient bone and navigate from the roots. An intraoral scan was then taken to produce a custom-made expander that could be mounted onto the bone screws.

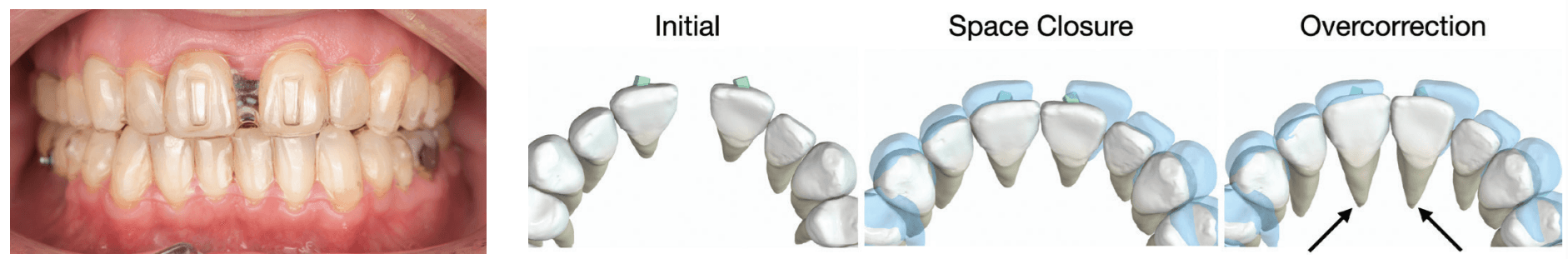

Following the successful orthopedic expansion, aligners were employed to close the diastema and restore the occlusion.

The initial setup in the aligners software (Spark™ Approver™) yielded an esthetically pleasing result, with ideal incisor inclination. While aligners generally perform well in expressing root movements, clinicians should anticipate that not all lingual root torque will be fully expressed in the upper incisors. To prevent retroclination and a steep interincisal angle, an additional 10° of palatal root torque should be incorporated into the ideal inclination.

The result shows an adequate overjet and overbite in both the incisors and the posterior teeth. The palate is now dome-shaped, allowing for proper tongue positioning. Additionally, after the palatal expansion, the patient ceased to snore.

Case report No. 2

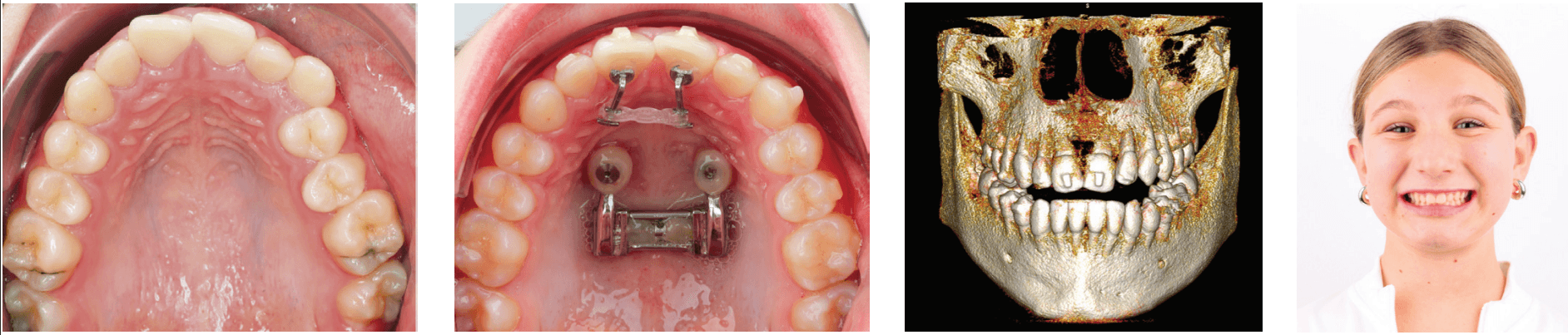

A 12-year-old female presented with her mother to evaluate a need for orthodontic treatment.

Clinical examination revealed maxillary transverse deficiency, high-arched palate, mild crowding, and enlarged tonsils. The mother reported that the patient exhibited mouth breathing and “loud breathing” sounds during sleep. To further assess nasal breathing, the patient completed the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) questionnaire, which indicated nasal obstruction. A home sleep study showed an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 6.4, confirming the presence of moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Patient also was referred to an ENT specialist.

Although the patient’s malocclusion could be corrected with dental expansion, skeletal expansion was chosen to achieve greater effect on the nasal cavity. Her DOME approach aimed to enhance nasal breathing both during wakefulness and sleep.

A bone-borne expander was selected to maximize skeletal expansion while minimizing dentoalveolar bending. Aligners were then used to restore the occlusion while the expander remained on the palate as a skeletal retainer for another 6 months.

After maxillary expansion, the mother reported that the patient’s breathing during sleep had become silent and that she now slept with her mouth closed. Additionally, the patient’s NOSE score improved from 6/20 to 0/20 — indicating a significant improvement in nasal breathing. The patient also noted that she previously woke up during the night, but this ceased after orthopedic expansion of the maxilla.

After completion of orthodontic treatment, a repeat sleep study may help determine need of further treatment including tonsillectomy.

Discussion

Resolving nasal obstruction is central to the care of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Nasal breathing confers significant advantages over mouth breathing during sleep, particularly with the physiologic stimulation of upper airway dilator muscles.16 Effective treatment of SDB is based on changing the negative pressure that can collapse the downstream pharyngeal airway. This is the critical negative pressure, referred to as P-crit, and is the basis of anatomic treatment of SDB.17 Slower and smoother airflow through the internal nasal valve results in less negative pressure to collapse pharyngeal muscles during sleep. Procedures such as septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and upper lateral cartilage grafts including spreaders reduce and realign structures of the INV. To expand the actual INV surface area with volumetric increase of the nasal passage, maxillary expansion is our most efficient means today. Beyond changes to the INV to improve nasal breathing, expansion of the maxilla also allows the tongue to be positioned favorably during sleep. This process is further augmented by breathing and myofunctional exercises.18,19

A great day begins with consistent, high-quality sleep. One of the most prevalent, but under-diagnosed and under-treated detractors, is sleep-disordered breathing. Ranging from snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), airflow interruptions during sleep take a detrimental toll on cognitive, mental, and physical health. In 2001, Dr. Christian Guilleminault called upon the dental profession to help, stating that “dentists and orthodontists have the greatest opportunity to [identify these patients] … and may obviate the need for aggressive surgical treatment later in life.”16 In the past, the collaboration of an orthodontist and surgeon to treat SDB began with maxillomandibular advancement (MMA). MMA is still needed for severe, persistent OSA, or patients with concomitant dentofacial deformity. Today, for mild OSA and UARS patients, the creation of a dome-shaped palate by the orthodontist, alongside any necessary intranasal treatments for SDB fills in the gap (puns intended again). As restoring sleep airway health is a gateway to wellness, the contemporary orthodontist is the chief architect of the “dome” to breathe.

Read more on the importance of nasal breathing and its affect on the direction of mandibular growth in this article by Dr. Nelson J. Oppermann. https://orthopracticeus.com/the-importance-of-nasal-breathing-and-its-effect-on-the-direction-of-mandibular-growth/

References

- Heinzer R, Vat S, Marques-Vidal P, Marti-Soler H, Andries D, Tobback N, Mooser V, Preisig M, Malhotra A, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Tafti M, Haba-Rubio J. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015 Apr;3(4):310-318. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00043-0. Epub 2015 Feb 12.

- Chandra RK, Patadia MO, Raviv J. Diagnosis of nasal airway obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009 Apr;42(2):207-225, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.004.

- Rhee JS, Weaver EM, Park SS, Baker SR, Hilger PA, Kriet JD, Murakami C, Senior BA, Rosenfeld RM, DiVittorio D. Clinical consensus statement: Diagnosis and management of nasal valve compromise. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Jul;143(1):48-59. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.04.019.

- Kiki A, Özdoğan A, Kiki MA, Genç YS. Bibliometric Analysis of Maxillary Expansion Publications Trends. Turk J Orthod. 2024 Sep 30;37(3):193-200. doi: 10.4274/TurkJOrthod.2023.2023.113.

- Gray LP. Results of 310 cases of rapid maxillary expansion selected for medical reasons. J Laryngol Otol. 1975 Jun;89(6):601-614. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100080804.

- Williams R, Patel V, Chen YF, Tangbumrungtham N, Thamboo A, Most SP, Nayak JV, Liu SYC. The Upper Airway Nasal Complex: Structural Contribution to Persistent Nasal Obstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Jul;161(1):171-177. doi: 10.1177/ 0194599819838262.

- Iwasaki T, Yoon A, Guilleminault C, Yamasaki Y, Liu SY. How does distraction osteogenesis maxillary expansion (DOME) reduce severity of obstructive sleep apnea? Sleep Breath. 2020 Mar;24(1):287-296. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-01948-7. Epub 2019 Dec 10.

- Abdelwahab M, Yoon A, Okland T, Poomkonsarn S, Gouveia C, Liu SY. Impact of Distraction Osteogenesis Maxillary Expansion on the Internal Nasal Valve in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Aug;161(2):362-367. doi: 10.1177/0194599819842808.

Epub 2019 May 14. - Liu SY, Guilleminault C, Huon LK, Yoon A. Distraction Osteogenesis Maxillary Expansion (DOME) for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients with High Arched Palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Aug;157(2):345-348. doi: 10.1177/0194599817707168. Epub 2017 Jul 4.

- Yoon A, Guilleminault C, Zaghi S, Liu SY. Distraction Osteogenesis Maxillary Expansion (DOME) for adult obstructive sleep apnea patients with narrow maxilla and nasal floor. Sleep Med. 2020 Jan;65:172-176. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.002. Epub 2019 Jun 13.

- Yoon A, Kim TK, Abdelwahab M, Nguyen M, Suh HY, Park J, Oh H, Pirelli P, Liu SY. What changes in maxillary morphology from distraction osteogenesis maxillary expansion (DOME) correlate with subjective and objective OSA measures? Sleep Breath. 2023 Oct;27(5):1967-1975. doi: 10.1007/s11325-022-02761-5. Epub 2023 Feb 20.

- Liu SY, Ibrahim B, Abdelwahab M, Chou C, Capasso R, Yoon A. A Minimally Invasive Nasal Endoscopic Approach to Distraction Osteogenesis Maxillary Expansion to Restore Nasal Breathing for Adults with Narrow Maxilla. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2022 Nov-Dec;24(6):417-421. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2021.0154. Epub 2022 Feb 17.

- Liu SY, Yoon A, Abdelwahab M, Yu MS. Feasibility of distraction osteogenesis maxillary expansion in patients with persistent nasal obstruction after septoplasty. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022 Jun;12(6):868-871. doi: 10.1002/alr.22931. Epub 2022 Jan 5.

- Jara SM, Thuler ER, Hutz MJ, Yu JL, Cheong CS, Boucher N, Evans M, Dedhia RC. Posterior Palatal Expansion via Subnasal Endoscopy (2PENN) for Maxillary Deficiency: A Pilot Study. Laryngoscope. 2024 Apr;134(4):1970-1977. doi: 10.1002/lary.31060. Epub 2023 Sep 29.

- Thuler E, Rabelo FAW, Yui M, Tominaga Q, Dos Santos V Jr, Arap SS. Correlation between the transverse dimension of the maxilla, upper airway obstructive site, and OSA severity. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Jul 1;17(7):1465-1473. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9226.

- Fitzpatrick MF, McLean H, Urton AM, Tan A, O’Donnell D, Driver HS. Effect of nasal or oral breathing route on upper airway resistance during sleep. Eur Respir J. 2003 Nov;22(5):827-832. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00047903.

- Carberry JC, Amatoury J, Eckert DJ. Personalized Management Approach for OSA. Chest. 2018 Mar;153(3):744-755. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.011. Epub 2017 Jun 16..

- Camacho M, Certal V, Abdullatif J, Zaghi S, Ruoff CM, Capasso R, Kushida CA. Myofunctional Therapy to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sleep. 2015 May 1;38(5):669-675. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4652.

- Cavalcante-Leão BL, de Araujo CM, Ravazzi GC, Basso IB, Guariza-Filho O, Taveira KVM, Santos RS, Stechman-Neto J, Zeigelboim BS. Effects of respiratory training on obstructive sleep apnea: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2022 Dec;26(4):1527-1537.. doi: 10.1007/s11325-021-02536-4. Epub 2021 Dec 1.

- Guilleminault C, Quo SD. Sleep-disordered breathing. A view at the beginning of the new Millennium. Dent Clin North Am. 2001 Oct;45(4):643-656.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Claudia Pinter, DMD, is an orthodontist in private practice in Vienna and Wels, Austria, specializing in esthetic orthodontic treatments with aligners. She is also an Affiliate Professor at Nova Southeastern University in Florida. Her passion for education led her to become the Course Director for the Fellowship in Aligner Orthodontics at Ripeglobal. In 2024, she received the Award for Best Aligner Case at the European Aligner Society Congress. A published author in peer-reviewed journals, Dr. Pinter regularly lectures at international dental, orthodontic, and sleep conferences.

Claudia Pinter, DMD, is an orthodontist in private practice in Vienna and Wels, Austria, specializing in esthetic orthodontic treatments with aligners. She is also an Affiliate Professor at Nova Southeastern University in Florida. Her passion for education led her to become the Course Director for the Fellowship in Aligner Orthodontics at Ripeglobal. In 2024, she received the Award for Best Aligner Case at the European Aligner Society Congress. A published author in peer-reviewed journals, Dr. Pinter regularly lectures at international dental, orthodontic, and sleep conferences. Dr. Stanley Liu, MD, DDS, FDSRC(ed), FACS, is the Chair of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery at Nova Southeastern University and Director of the NSU Breathe and Sleep Wellness Center. Previously, he was an Associate Professor of Otolaryngology at Stanford University School of Medicine, where he directed the sleep surgery fellowship. He has published over 120 original articles, with an emphasis on sleep-disordered breathing. His updated surgical and medical treatment of OSA is published in textbooks across a broad range of specialties. He has been honored as a keynote speaker at both the American and World Sleep Medicine Congresses. You can also find him at

Dr. Stanley Liu, MD, DDS, FDSRC(ed), FACS, is the Chair of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery at Nova Southeastern University and Director of the NSU Breathe and Sleep Wellness Center. Previously, he was an Associate Professor of Otolaryngology at Stanford University School of Medicine, where he directed the sleep surgery fellowship. He has published over 120 original articles, with an emphasis on sleep-disordered breathing. His updated surgical and medical treatment of OSA is published in textbooks across a broad range of specialties. He has been honored as a keynote speaker at both the American and World Sleep Medicine Congresses. You can also find him at