CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to identify the role of specialists in the treatment of cleft palate and focus on the role of the orthodontist.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify the parts of the interdisciplinary team for collaboration on cleft palate care.

- Define cleft palate.

- Realize the timing of clinical team

- Recognize the role of the orthodontist and possible intervention in certain time frames of the patient’s life.

Drs. Chung How Kau, John Grant, Rene Myers, Kathlyn Powell, Nathaniel H. Robin, and Cassi Smola discuss a condition that can affect children from birth to teen years

Introduction

Orthodontists play an important role in the diagnosis and management of dentofacial anomalies and craniofacial malformations. Careful evaluation of facial growth, development of the dentition, and establishment of an optimal occlusion are important components of craniofacial care. In the instance of a patient with a cleft lip and palate (CLP), this begins in utero and often continues until the patient reaches adulthood. This seemly long period of patient care is unique to patients with craniofacial anomalies and is crucial to the overall success of the patient’s rehabilitation.

The orthodontist, however, is not alone and has to collaborate with a multi-disciplinary team that includes the pediatric craniofacial plastic surgeon, neurosurgeon, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, otolaryngologist, pediatrician, geneticist, dentist, speech and language pathologist, audiologist, nutritionist, psychologist, sleep medicine physician, social worker, and nursing staff.1 Each member of this team brings a unique perspective to cleft care, and their expertise enriches the patient outcome tremendously. This article will focus only on the role of the orthodontist in the team care and provides an overview of the crucial interventional periods.

Cleft lip and palate

A cleft lip and palate (CLP) occur when there is a failure of fusion of the facial structures between the 5th and 10th week of gestation.2 A cleft lip occurs when the frontonasal and maxillary processes fail to fuse during the 5th to 8th week of embryonic development. During the 8th to 10th week, a failure of fusion of the palatal shelves will lead to a cleft palate.

In modern days, pre-natal diagnosis of an oro-facial cleft using ultrasound technology is possible after at least 15 weeks of gestation. This type of technology has been used for over 30 years, but only cleft lip can be visualized with a high degree of certainty, while cleft palate is almost impossible to detect.

Timing of clinical team interventions

From the time of the birth of the child until adulthood, an entire team involvement is highly desirable. The American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association has established standards for each cleft team and ensures the long-term success of patient care. These standards include team composition, team management and responsibilities, patient and family/care giver communication, cultural competence, psychological and social services, and outcomes assessment. The guidelines further state that the team must have, as a minimum core, professionals from the speech language pathology, surgery, and orthodontic specialties who participate in team meetings. Each patient should also have access to the other previously mentioned members of the team. The team care approach has been greatly recommended after studies from established cleft teams in European countries showed that centers with centralized care had better pooled resources, and the clinical outcomes were better compared to those centers that had a low volume of patients.

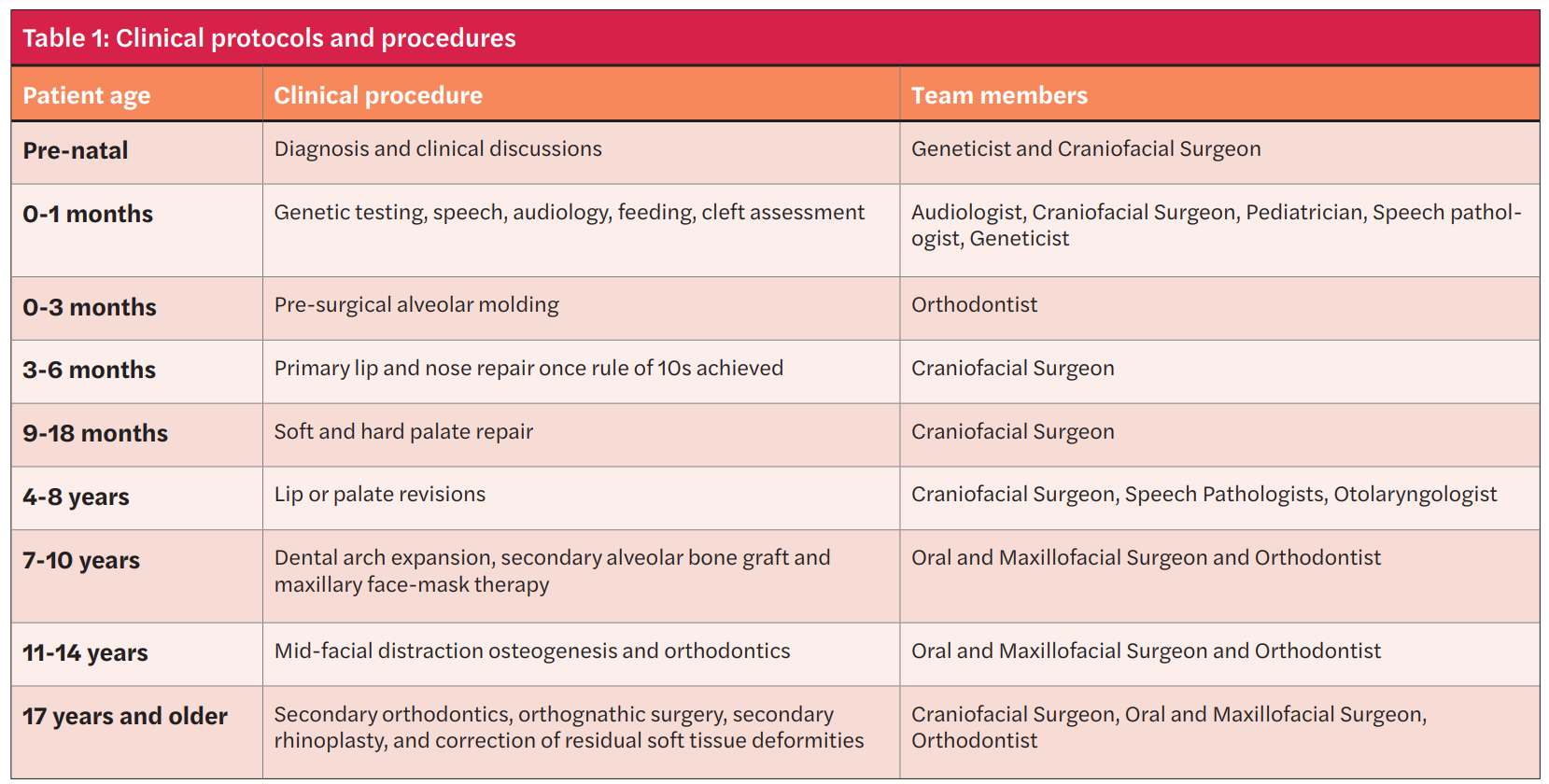

Exact clinical protocols are slowly beginning to be established as better evidence becomes available. At present, varying protocols and timing of treatment exists. The timing of the University of Alabama (UAB) cleft team’s involvement is summarized in Table 1.

Role of the orthodontist

The role of the orthodontist is crucial to the success of patient care. The care of the cleft patient may be broken into four main time frames which include the following:

- 0-3 months,

- 7-10 years,

- 10-14 years,

- 17 years and above

0-3 Months: pre-surgical naso-alveolar molding (PNAM)

Pre-surgical alveolar molding is one of the first procedures carried out by the orthodontist in CLP patients.3 The procedures include a lip tape, alveolar molding, naso-alveolar molding, and lip adhesion. Often, a patient will present in the ward or at the team clinic within the first 10 days of life. Once the patient (parents) consent(s) to treatment, the orthodontist swaddles the baby and takes a dental impression of the alveolus with a polyvinyl siloxane medium body impression material. The working time is approximately 90 seconds, and it is crucial not to remove the impression tray too early. The baby may fuss or cry a little but often calms down after a few seconds. At the Cleft and Craniofacial Center at Children’s of Alabama, the baby often leaves with a lip tape in place. This taping process is done by squeezing the soft tissues around the cleft tightly together and securing it with a lip tape (Steri-Strip (3M) or DynaCleft® tape) (Figure 1).

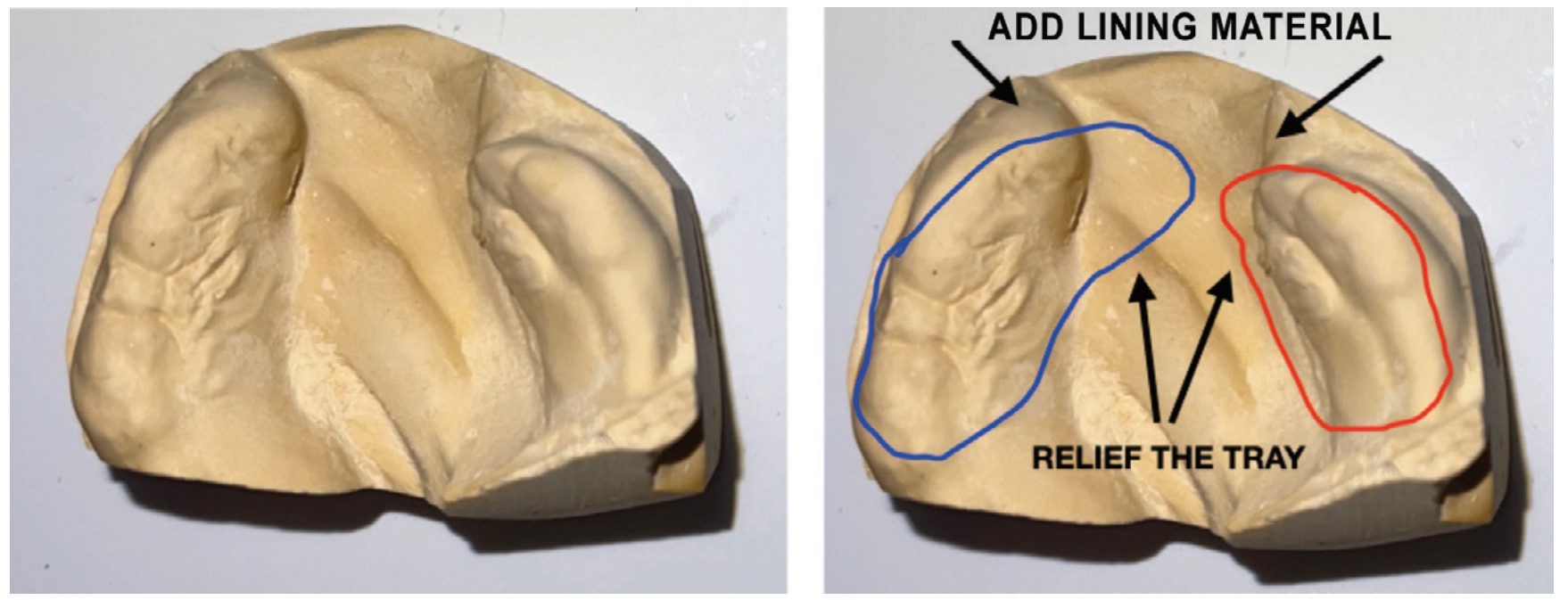

Patients normally return to the cleft team after a week, and the actual alveolar molding process begins. The goal of the molding process is to carefully approximate the alveolar segments together and to greatly reduce the size of the cleft defect (Figure 2). This is done by strategically and incrementally adding material to the alveolar plate and securing the plate back in the patient’s mouth using elastic tape. In some instances, small amounts of denture adhesives may also help to secure the alveolar plate to the patient’s gums.

When the alveolar segments are approximated to within 4 mm, the nasal molding process can begin. Some centers add a nasal stent to the alveolar plate, while others may use an external elastic nasal elevator similar to ones from DynaCleft. Patients normally return to the cleft team for adjustments every 10 days, and this process goes on until the patient is ready for surgery at 4 months. Patients seem to adapt better the earlier the treatment begins, and the alveolar plate can also help with feeding as it molds the alveolus.

Studies have found a significant reduction in size of the cleft and improvements in nasal symmetry with PNAM.4 As a result, many agree that the procedure is effective and improves overall esthetics and nasal symmetry.

7-10 years: dental arch expansion, secondary alveolar bone grafting, and maxillary face-mask therapy

Secondary alveolar bone grafting is performed by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon at the ages of 7-11 years old to close the oro-nasal gap.5 There is less consensus on the timing of this procedure with some centers opting to start early (6-7 years), while others wait on the root development of the permanent maxillary canines (10-11years).6,7 The orthodontist may be involved before the alveolar grafting procedure depending on how collapsed the alveolar segments are. It is important to note that too aggressive arch expansion may open too much of the cleft defect and compromise the bony support of the teeth directly next to the cleft defect. Careful communication within the surgeon is necessary to ensure a good alveolar bone graft outcome.

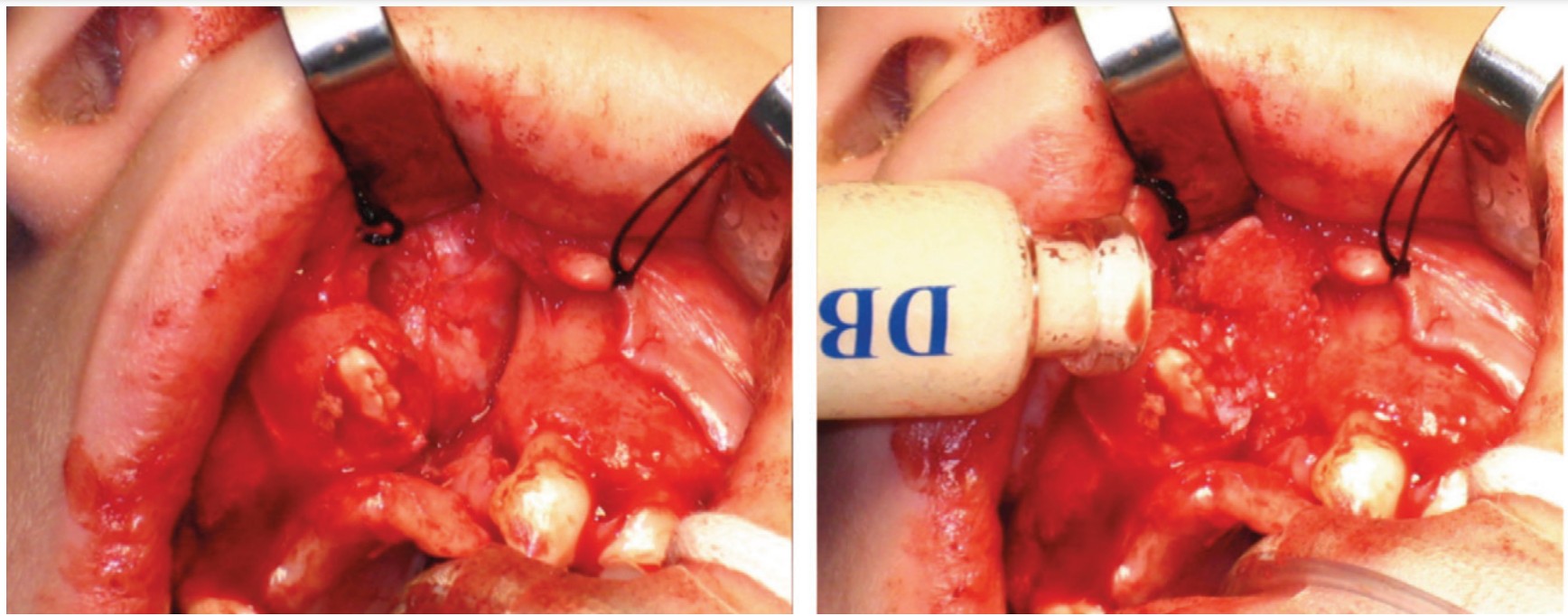

The UAB protocol8 involves early extraction of primary teeth adjacent to the cleft followed by about 1 month for the keratinized gingival tissue to re-establish itself. The bone graft is done using the patient’s iliac bone and occurs before the permanent lateral incisors or canines erupt. Good outcomes may be expected from the secondary alveolar bone graft9 (Figure 3). As dental development occurs, dentofacial orthopedics with face mask therapy may be prescribed.

10-14 years: distraction osteogensis and orthodontics

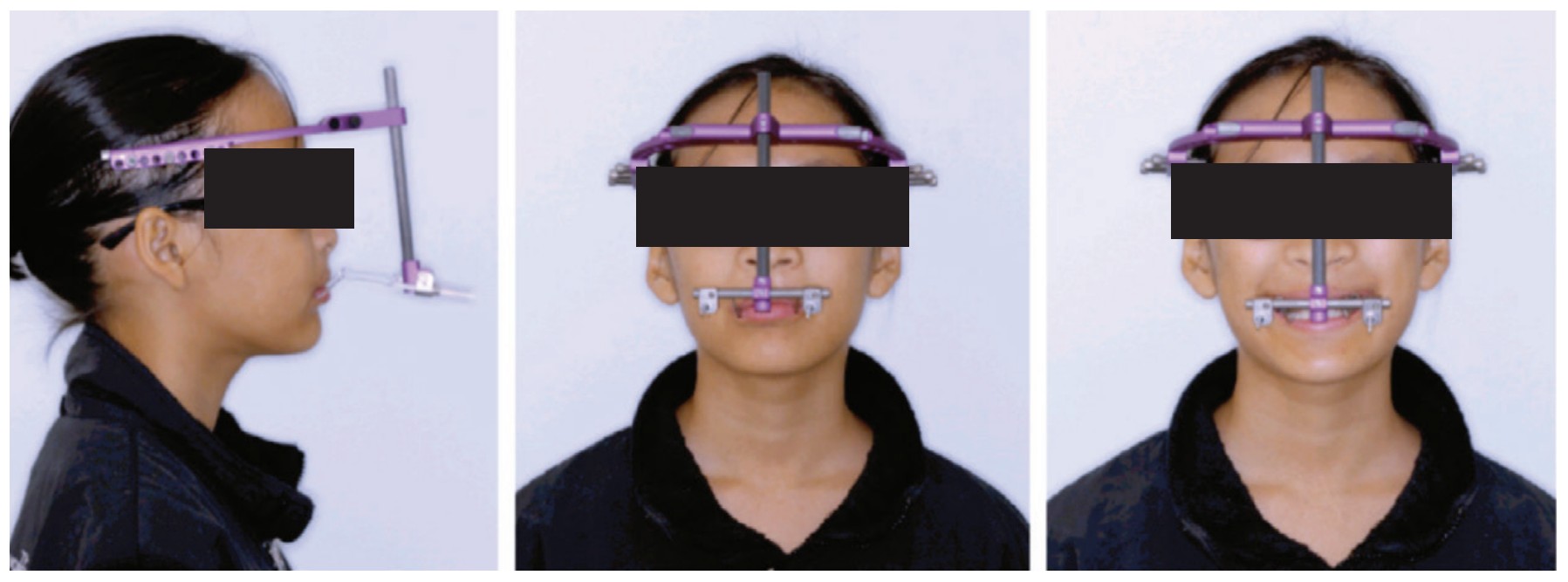

In some instances, surgical distraction osteogenesis may be required to improve the maxillary deficiency. The concept of osteogenic distraction was popularized by a Russian surgeon Dr. Gabriel Ilizarov and later adapted to maxillary hypoplasia by using a Rigid External Distractor (RED) by Drs. John W. Polley and Alvaro A. Figueroa. Internal maxillary distractors have also been described and used.

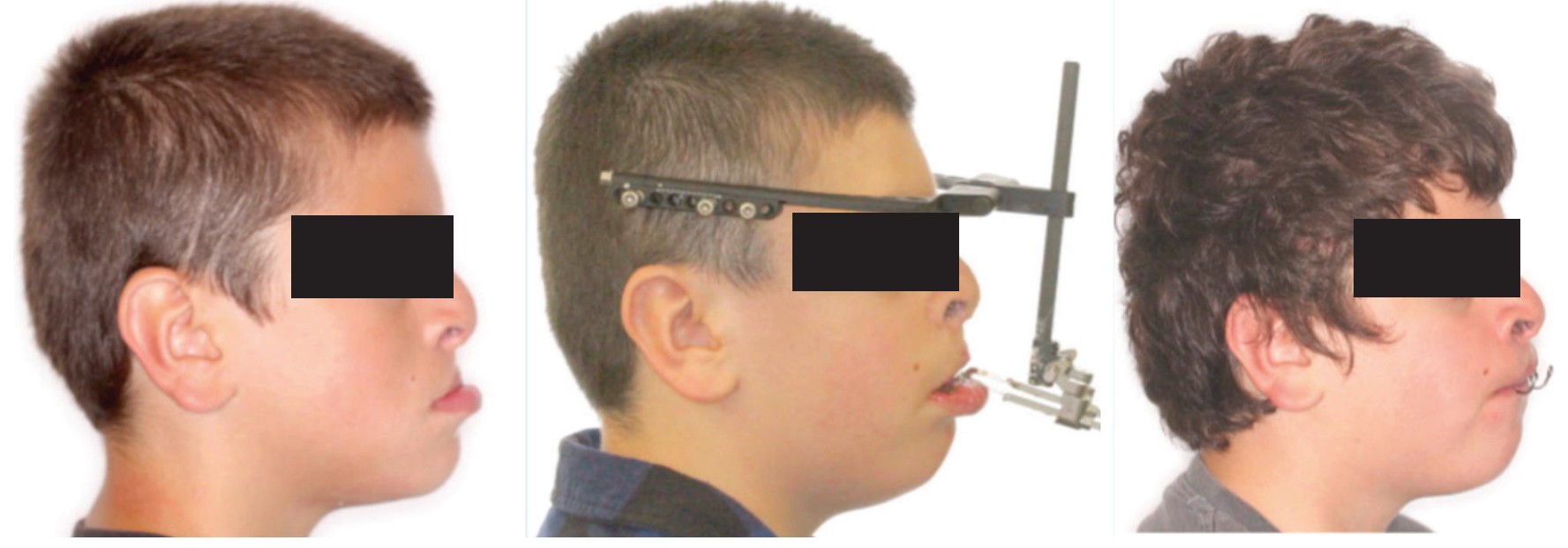

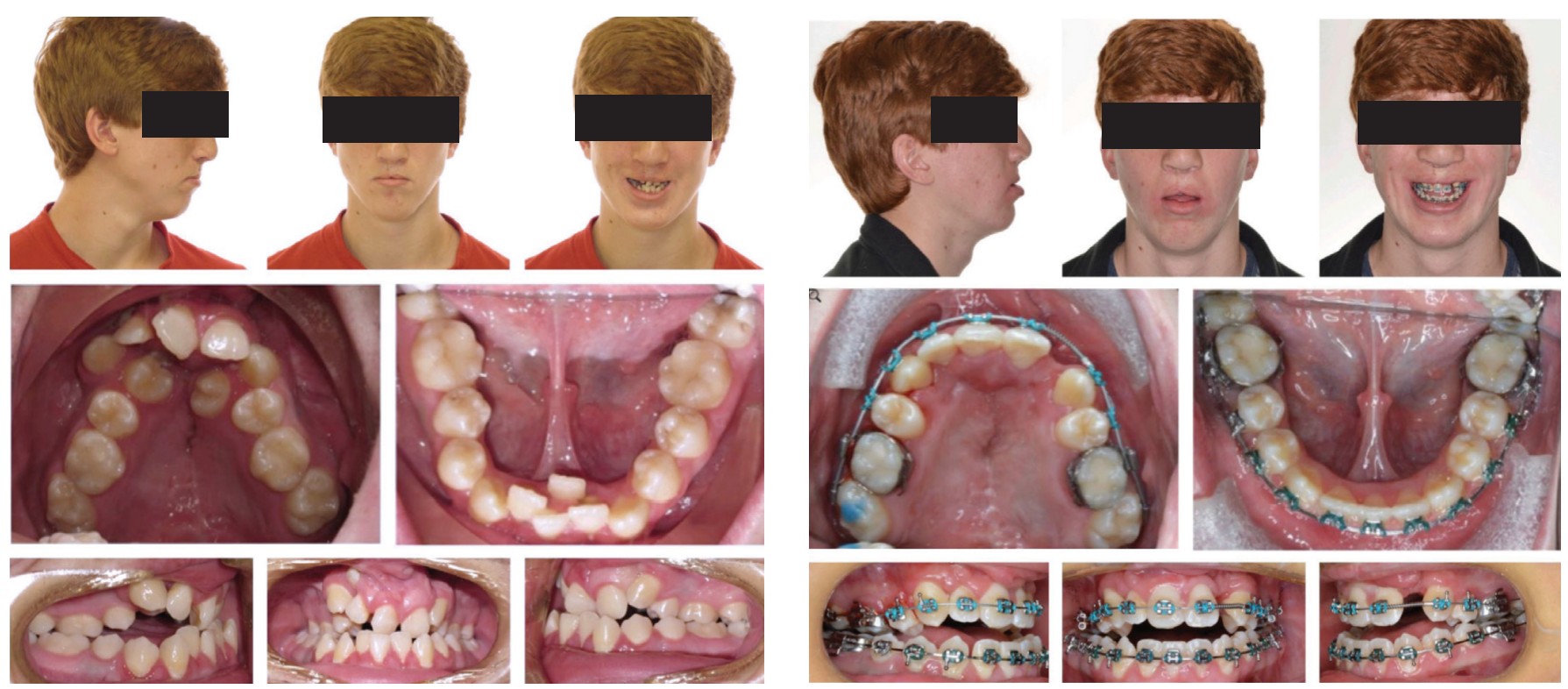

These techniques are advocated in patients with significant mid-facial hypoplasia with negative dental overjets of more than -6 mm. When a RED is used, the orthodontist constructs an orthodontic appliance which comprises a labio-lingual rigid structure, metal arms that extend to the just in front of the lips, and an occlusal bite ramp to help disarticulate the occlusion. This appliance is placed intraorally before the RED surgery. The surgery involves conventional LeFort 1 osteotomies. After a 7-day latency period, the RED distractor is activated at a rate of 1 mm per day until the desired maxillary movement has occurred (Figure 4). It is not unusual to overcorrect the occlusion by 4-5 mm as some relapse is expected.10,11 Internal distractors have also been used to improve the mid-facial hypoplasia. It is important to note that the vectors may not be uniformly distributed, and careful attention needs to be in place to support the maxillary dentition (Figure 5). Maxillary distraction seems to help with the psycho-social aspect of the patient and has a positive outcome during the crucial formative years of patients developing an identity. Once the sagittal jaw relationship has been corrected, conventional orthodontics can begin. This stage of orthodontics normally lasts for 2 years (Figure 6).

17 years and above: secondary orthodontics and orthognathic surgery

It is well documented that patients continue to mature and grow past 17 years of age. In some instances, the established occlusion from orthodontics can be undone by unexpected growth. A short course of pre-surgical orthodontics is performed followed by orthognathic surgery (Figure 7).

Conclusion

Cleft care by the orthodontist is an important part of patient success. This care should be performed by one who is experienced and has access to the resources of the cleft and craniofacial team. The successful rehabilitation of patients is high and predictable in modern days.

Dr. Thomas Wilson shared his technique for minimizing cleft palate surgery in newborns. Read about it here: https://orthopracticeus.com/ce-articles/treating-cleft-palate-presurgical-nasoalveolar-molding-pnam/

References

- Paradowska-Stolarz A, Mikulewicz M, Duś-Ilnicka I. Current Concepts and Challenges in the Treatment of Cleft Lip and Palate Patients-A Comprehensive Review. J Pers Med. 2022 Dec 19;12(12):2089.

- Candotto V, Oberti L, Gabrione F, Greco G, Rossi D, Romano M, Mummolo S. Current concepts on cleft lip and palate etiology. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2019 May-Jun;33(3 Suppl. 1):145-151. Dental supplement.

- Alzain I, Batwa W, Cash A, Murshid ZA. Presurgical cleft lip and palate orthopedics: an overview. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2017 May 31;9:53-59.

- Clark SL, Teichgraeber JF, Fleshman RG, Shaw JD, Chavarria C, Kau CH, Gateno J, Xia JJ. Long-term treatment outcome of presurgical nasoalveolar molding in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate. J Craniofac Surg. 2011 Jan;22(1):333-336.

- Weissler EH, Paine KM, Ahmed MK, Taub PJ. Alveolar Bone Grafting and Cleft Lip and Palate: A Review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Dec;138(6):1287-1295.

- Wallender A, Stone J. Bone Graft and Reconstruction of the Cleft Maxilla: Alveolar Bone Graft and Midface Distraction. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2022 Mar;30(1):37-44.

- Mundra LS, Lowe KM, Khechoyan DY. Alveolar Bone Graft Timing in Patients With Cleft Lip & Palate. J Craniofac Surg. 2022 Jan-Feb 01;33(1):206-210.

- Miller LL, Kauffmann D, St John D, Wang D, Grant JH 3rd, Waite PD. Retrospective review of 99 patients with secondary alveolar cleft repair. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010 Jun;68(6):1283-1289.

- Kau CH, Medina L, English JD, Xia J, Gateno J, Teichgraber J. A comparison between landmark and surface shape measurements in a sample of cleft lip and palate patients after secondary alveolar bone grafting. Orthodontics (Chic.). 2011 Fall;12(3):188-195.

- Alkhouri S, Waite PD, Davis MB, Lamani E, Kau CH. Maxillary Distraction Osteogenesis in Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Patients with Rigid External Distraction System. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2017 Jan-Jun;7(1):57-63.

- Vaughan SM, Kau CH, Waite PD. Novel Three-Dimensional Understanding of Maxillary Cleft Distraction. J Craniofac Surg. 2016 Sep;27(6):1462-1464.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores