CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

The aim of this article is to discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of TMJ osteoarthritis.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions on page 45 to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize the underlying mechanisms of the disease and its prevalence.

- Identify some forms of arthritis.

- Define some necessary determinants for diagnosis of TMJ OA.

- Recognize the pathophysiology of TMJ OA.

- Realize forms of diagnosis, and management of TMJ OA.

Dr. Harold F. Menchel discusses a disorder that can have significant effects on orthodontic treatment planning and treatment

Dr. Harold F. Menchel discusses a disorder that can have significant effects on orthodontic treatment planning and treatment

Abstract

A past article has discussed the ortho-dontic implications of TMJ arthritis.1 In this article, the author proposes a mechanism of infectious TMJ arthritis in infants related to otitis media.

This infection causes condylar lysis and altered growth causing occlusal changes.2 This disorder will have significant effects on orthodontic treatment planning and treatment. A case history is presented to support this hypothesis.

Introduction

Septic bacterial joint arthritis affects populations of older patients (greater than 55 years) and infants. The most common joints affected are the hip and knee in children. Over a third of the incidence is in infants below the age of 2. The incidence is estimated at 6/100,000.3

The most common isolated organisms are Staph aureus and H. influenzae. This is a focal infection and needs to be distinguished from Lyme arthritis, which is more systemic and caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi.4,5 There are previous reports of septic TMJ arthritis related to middle ear infections in the literature.6,7,8,9

There are also reports of spread of bacteria to the joints from bacterial pharyngitis caused by streptococcal infections. It is controversial, however, if this is from direct infection or is a reactive arthritis.10

Case history

Subjective

A 13-year old patient was referred to an orofacial pain dentist with symptoms of severe left ear pain, preauricular swelling, and limited opening. She reported occasional mild pain on the left only over the past few years, which had increased over the past month. She was unable to chew or open her mouth without pain. She was unaware of bruxism. There was no temporal pattern to her pain. The patient reported occasional moderate temporal headache on the left side only.

Medical history

Positive for numerous episodes of otitis media as infant with pressure equalization (PE) tubes placed to drain infection. The medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

Dental history

The patient had been treated orthodontically with a palatal expander to correct a unilateral crossbite at age 8. The records were supplied and indicated that the crossbite was reduced with centered midline. The patient had reported bite changes and was scheduled for definitive orthodontic treatment when she was referred for TMD pain and dysfunction.

Objective findings

The patient had severe pain to palpation of the left TMJ with mild pain on the right. She also had severe pain in the muscles of mastication more on the left. There was evident hyperalgesia in the left preauricular area, but no swelling was noticed during examination. She had no cervical pain. Occlusal evaluation revealed a Angle Class III canine relationship on the right and a

Angle Class I relationship on the left with the canine in crossbite. Maximum intercuspation = centric relation, and there was no evident slide or shift on closing. She deviated to the left on opening and protrusion.

Her maximum intercisal opening was 35 mm with a “soft” end feel. After ice and gentle manipulation, the patient opened to 45 mm. There was a midline shift to the left of 3 mm, decreased posterior overjet on the left, increased posterior overjet on the right. Vertical overlap was 15%, and horizontal overlap 1.5 mm on the right and 2.5 mm on the left with an evident open bite in the right anterior.

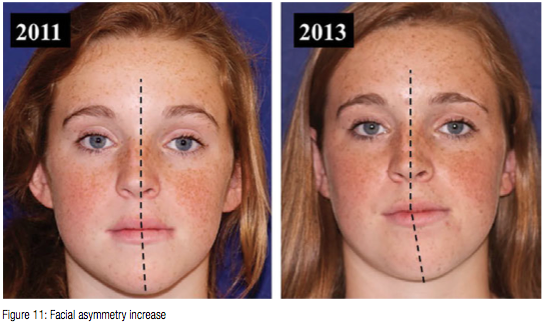

The patient has a facial asymmetry to the left (Figure 1).

Imaging

Imaging for the patient is below. MRI imaging was initially planned, but due to patient’s progress, this was deferred. No initial TMJ surgery was anticipated.

Diagnosis

- Septic arthritis left TMJ

- Myalgia

- Protective co-contraction

Plan

TMD – Pain management involved standard TMD conservative therapy,12 resting the mandible with soft diet and behavioral modification (no gum chewing, no resting chin on hand, etc.), and home care (ice for 72 hours followed by moist heat).

The patient was prescribed NSAID (Naprosyn 220 mg BID [Aleve®]), acetaminophen/diphenhydramine (Tylenol® PM), and QHS to aid sleep and for pain.  She was referred to physical therapy for further evaluation, TMJ mobilization, and modalities as necessary for reduction of inflammation and range of motion improvement. A lower flat plane orthotic was placed with mandatory nightwear and day wear as necessary for pain. The occlusion was very unstable, and splint adjustments were made once a week for the first month.

She was referred to physical therapy for further evaluation, TMJ mobilization, and modalities as necessary for reduction of inflammation and range of motion improvement. A lower flat plane orthotic was placed with mandatory nightwear and day wear as necessary for pain. The occlusion was very unstable, and splint adjustments were made once a week for the first month.

The patient responded very well and in 6 weeks had minimal pain to loading, an opening of 50 mm with no deviation, or limitation in range of motion (ROM). She continues to wear the splint at night. The splint is checked at 3-month intervals. Notice the changes in Figure 7.

Occlusal — orthodontic

This patient has an unstable occlusion due to continuing condylar erosion and limited growth in the left condyle. Final orthodontic correction is contraindicated at this time and will not be done until full growth (in females 16-18 years). There is certainly indication in this case for possible orthognathic correction. Records are being taken annually to chart the progression of the disease. Although this is a unilateral lesion, further imaging and diagnosis will be necessary before the final treatment. Inflammatory arthritis needs to be ruled out. This will involve the protocols mentioned in a previous article in this series.1

This patient is now 15 and not yet at full growth. Her progress will be documented in further articles. Discussion

Discussion

This case history is proposed as a possible mechanism for degenerative joint disease in infants and children. This mechanism is shown in the following figure.

Although the incidence of TMJ septic arthritis is unknown and certainly uncommon, this author has seen a number of cases with similar presentation and history over the past 20 years. Injury, of course, cannot be ruled out as a cause, but in this case, and similar cases, there are no reports of injury. TMJ injury is rare in children.14 Notice that the joint changes were evident on a previous Panorex taken 5 years before when the patient was 8 years old.

Also notice how the facial asymmetry and malocclusion is increasing in the next figures that follow.

Clinical implications and conclusions

The author is proposing a mechanism for TMJ arthritic degeneration in children, which could be overlooked.15,16 It is essential that in infants with perforation of the tympanic membrane (TM), either with PE tubes or from TM rupture, that these patients be treated more aggressively with antibiotics than for routine cases of otitis media to prevent septic arthritis. Pediatricians need to be aware of the possibility of this disease. This disorder can be screened at a young age and long-term treatment planning co-ordinated with the dentist, orofacial pain dentist, and oral surgeon. It needs to be differentiated from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA).17 In JRA, the lesions are almost always bilateral, and the patient will have a general feeling of malaise and migratory joint pain.

Rheumatology evaluation is always mandatory in these cases, and any long-term medical management should be under the care of this physician. If there is no systemic component to the arthritis, and it is a form of osteoarthritis, secondary to bacterial infection, medications are not indicated to alter the disease progression.

The responsibility falls on the orthodontist and pediatric dentist to diagnose and manage occlusal changes in these patients.18 Controlling mechanical stress is also vital in these patients, and if the patient is a bruxer, a hard acrylic night splint is recommended even without signs and symptoms of TMJ pain or dysfunction.

This article was presented at the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP) International Conference on Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders (ICOT) in Las Vegas in May 2014.

References

- Menchel HF. TMJ arthritis 2014: Essentials for the orthodontist, Part 1. Orthodontic Practice US. 2014;5(4):40-44.

- Yamada K, Satou Y, Hanada K, Hayashi T, Ito J. A case of anterior open bite developing during adolescence. J Orthod. 2001;28(1):19-24.

- Mathews CJ, Coakley G. Septic arthritis: current diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(4):457-462.

- Welkon CJ, Long SS, Fisher MC, Alburger PD. Pyogenic arthritis in infants and children: a review of 95 cases. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986;5(6):669-676.

- Morrey, BF, Bianco AJ Jr, Rhodes KH. Septic arthritis in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1975;6(4):923-934.

- Yamada K, Saito I, Hanada K, Hayashi T. Observation of three cases of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and mandibular morphology during adolescence using helical CT. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31(4):298-305.

- Regev E, Koplewitz BZ, Nitzan DW, Bar-Ziv J. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint as a sequelae of septic arthritis and neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(1):99-101.

- Hammoudi K, Manceau A, Cazeneuve N, Poulain D, Buis J, Soin C. Childhood septic temporomandibular arthritis [in French]. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126(1):18-21.

- Güven O. A clinical study on temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children. J Craniofac. Surg. 2008;19(5):1263-1269.

- Nelson JD. The bacterial etiology and antibiotic management of septic arthritis in infants and children. Pediatrics. 1972;50(3):437-440.

- Honey OB, Scarfe WC, Hilgers MJ, Klueber K, Silveira AM, Haskell BS, Farman AG. Accuracy of cone-beam computed tomography imaging of the temporomandibular joint: comparisons with panoramic radiology and linear tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(4):429-438.

- Menchel HF. What is conservative care for TMD? TMJ and Facial Pain Institute Web site. https://www.tmjtherapy.com/splintherapyfortmj.html. Accessed August 6, 2014.

- Lacout A, Marsot-Dupuch K, Smokerb WR, Lasjaunias P. Foramen tympanicum, or foramen of Huschke: pathologic cases and anatomic CT study. AJNR Am J Neuroadiol. 2005;26(6):1317-1323.

- Fischer DJ, Mueller BA, Critchlow CW, LeResche L. The association of temporomandibular disorder pain with history of head and neck injury in adolescents. J Orofac Pain. 2006;20(3):191-198.

- Saslaw MM, Mishra S, Green M, Yellon R, Michaels MG. Suppurative arthritis complicating otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(5):475-476.

- Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Kurs-Lasky M. Acute otorrhea: bacteriology of a common complication of tympanostomy tubes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103(9):713-718.

- Weiss JE, Ilowite NT. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33(3):441–470

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guidelines on Acquired Temporomandibular Disorders in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Clinical Affairs Committee, Temporomandibular Joint Problems in Children Subcommittee. 2010;35(6):262-267.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores