Dr. Nelson J. Oppermann discusses nasal breathing as an essential component to optimal orthodontic results

Introduction

The effect of breathing patterns on facial growth of children has been well documented. Many articles indicate that nasal obstruction leads to respiration changes, which can influence the facial development pattern.

[userloggedin]

1-4

Linder-Aronson5 described the facial characteristic of “mouth-breathing individuals,” by the following:

- an incompetent lip seal

- a narrow upper arch

- retroclined mandibular incisors

- increased anterior face height

- steep mandibular plane angle

- retrognathic mandible

He also noticed that patients with large adenoids, due to breathing through the mouth, had a lower tongue position and unbalanced forces from the cheeks and tongue when compared to normal mouth breathers. Linder-Aronson observed that a lower mandibular position led to an extended head posture. Cephalometrically, a large anterior face height and increased mandibular plane angle can be noted in mouth-breathing patients, as well as short mandible ramus heights.

Linder-Aronson6 found changes in skeletal and dental variables toward normal after adenoidectomies. Growth of the mandibular ramus and condylar process of adenoidectomy patients was found to be greater than that in the control subjects7 due to the alteration in tongue position and autorotation of the mandible. However, a decrease in the mandibular plane angle requires more growth in posterior face height/ramus height than anteriorly. The intrusion of maxillary teeth may be possible with the use of intrusive devices or maxillary impaction surgery. Mandibular growth, when adenoidectomy is performed on severe nasopharyngeal obstruction individuals, was significantly greater when compared to control group 5 years after surgery8.

Based on these findings, it is imperative for the orthodontists to detect patients’ breathing patterns at an early age and refer them to an otorhinolaryngologist to perform the appropriate treatment.

This case report shows a mouth-breathing patient before treatment and 2 years after the adenoids were surgically removed. The patient completed comprehensive orthodontic treatment. Follow-up records until adulthood are presented.

Diagnosis and treatment plan /case presentation

A 7-year-old mouth breathing female patient presents with a Class II div 1 malocclusion, convex profile (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The lateral cephalometric radiograph shows noticeably large adenoid tissue present and a downward tip of the occlusal plane (Figure 3).

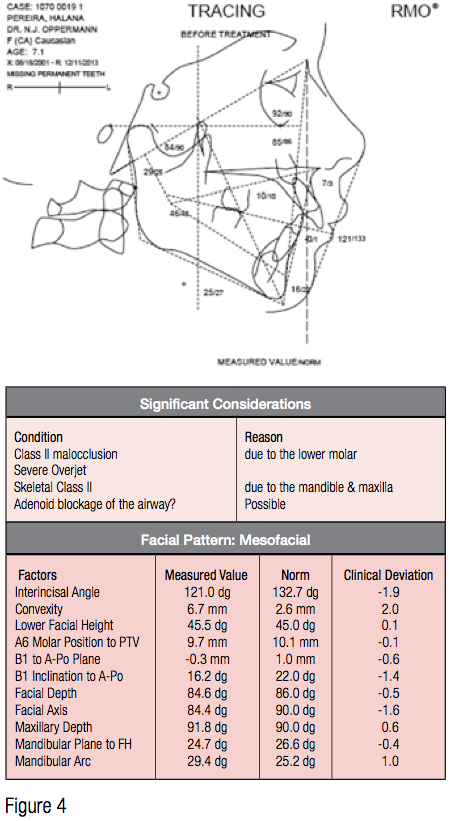

The lateral tracings were done by Rocky Mountain® Orthodontics Data Services® (RMODS®), and the patient was diagnosed with a large overjet, skeletal Class II condition with the mandible rotated clockwise when compared with the mean norms.

Immediately, the patient was referred to an otorhinolaryngologist for evaluation of the upper airway condition and to communicate the appropriate treatment plan.

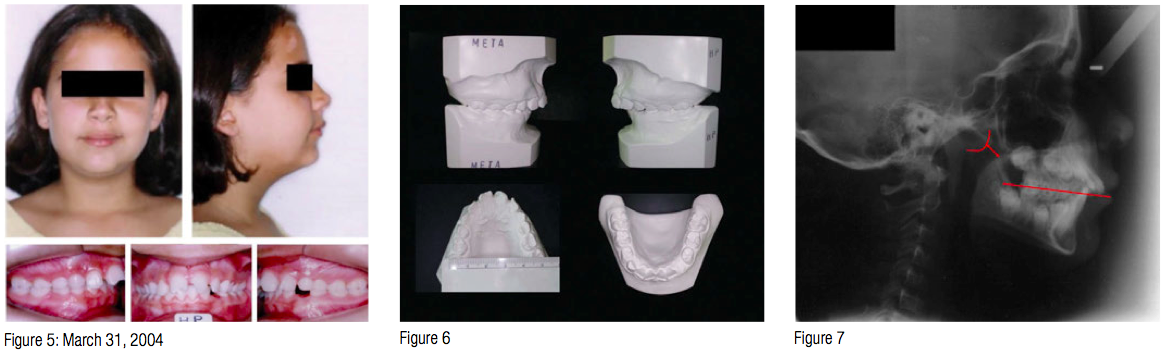

After the adenoidectomy, the patient disappeared resulting in 2 years and 6 months of no orthodontic work within this time frame. New records were taken (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The malocclusion remained similar, but the profile improved.

After the adenoidectomy, the patient disappeared resulting in 2 years and 6 months of no orthodontic work within this time frame. New records were taken (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The malocclusion remained similar, but the profile improved.

The functional occlusal plane improved (observe the T2 lateral ceph radiograph) with tipping back the posterior and raising the anterior, thus, facilitating the forward movement of the mandible (Figure 7). T1 and T2 before and after comparison can be seen in Figure 8.

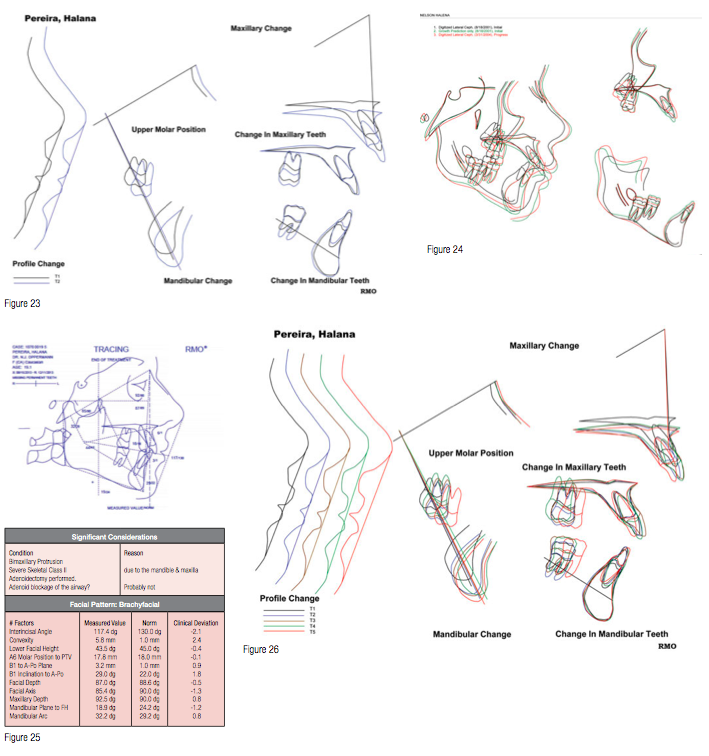

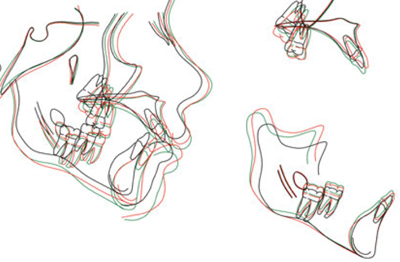

The mandible changed growth direction (Figure 23), and the mandible condyles grew in a healthier direction (Figure 24).

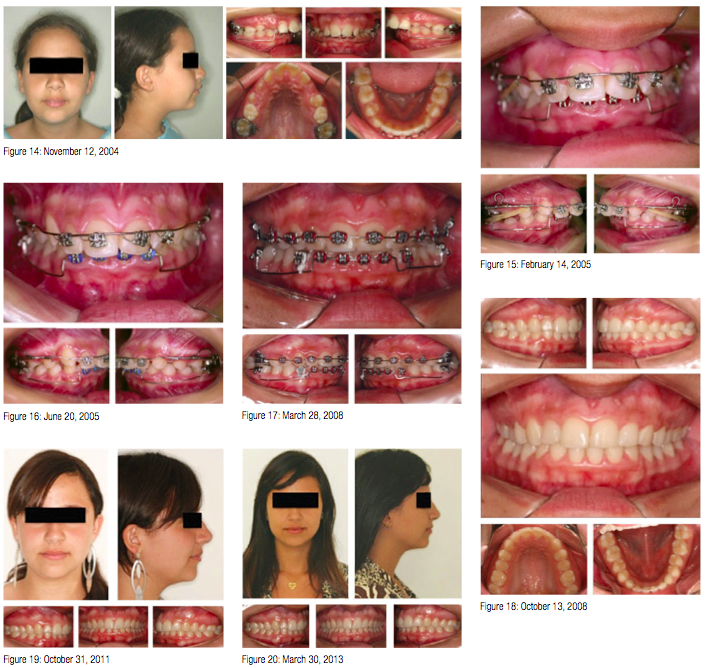

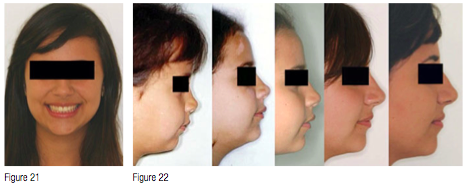

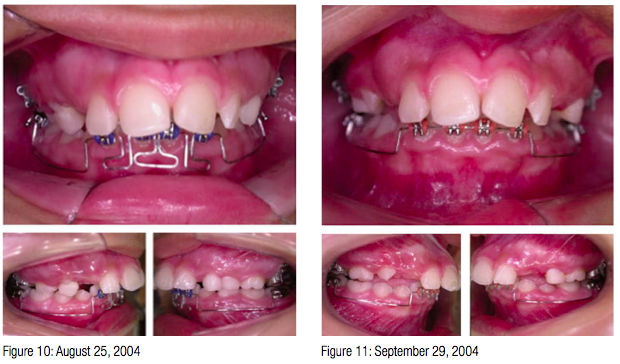

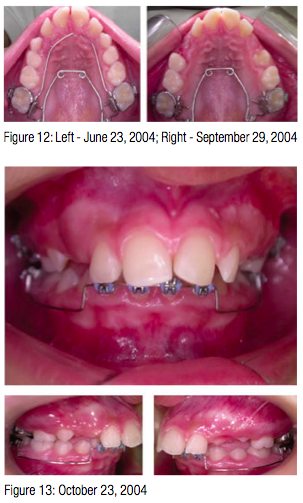

Figures 9 to 21 exhibit the treatment mechanics and follow-up appointments until adulthood at age 21. Notice the profile changes through the years in Figure 22.

Final tracings and superimpositions at 21 years old can be seen in Figure 25 and Figure 26.

Discussion

In order to express the maximum mandibular growth potential, it is imperative that the patient is able to breathe through his/her nose. This is the key in Class II cases where the mandible is retropositioned and growing downward.

Redirecting the growth of the mandible in a sagittal direction by counterclockwise rotation is fundamental to reducing the convexity and obtaining a more pleasant profile. The growth can be controlled by carefully monitoring the vertical aspect of the case, allowing for ramus growth. Additional outcomes are a decompressing of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ)9 and preventing molar growth and extrusion.

Monitoring the preceding conditions closely will allow the functional occlusal plane to react positively, which is a sign that the mandible is moving in the correct direction.

Conclusion

The overall function, specifically, nasal breathing, is imperative to obtain the best orthodontic results, independent of the treatment plan and appliances used.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores