Orthodontic treatment of a Class II division 1 malocclusion with severe maxillary gingival display by using mini-implants as anchorage

Abstract

A 21-year-old woman presented for consultation with chief complaints of “protrusive lips and a gummy smile.” The clinical examination showed a convex profile, a protrusive maxilla, excessively proclined and extruded maxillary incisors, and a pronounced Class II division 1 malocclusion.

[userloggedin]

Temporary Anchorage Devices (TADs) in the maxillary posterior and anterior dental region were used as anchorage for retraction and intrusion of her maxillary anterior teeth. The treatment eliminated her excessive maxillary gingival display and her protrusive profile, and corrected the overjet, overbite, and canine relationships. The patient ended up with a satisfactory occlusion and an attractive smile.

Introduction

Class II malocclusion is characterized by anteroposterior imbalance of the jaws, caused by bone dysplasia or by a combination of skeletal and dental factors. In Class II division 1 malocclusion, the overjet is excessive, and is usually associated with a deep bite, causing esthetic and functional problems that require orthodontic treatment. Proffit and Ackerman described three primary treatment approaches for correcting a Class II malocclusion associated with mandibular deficiency: growth modification to eliminate the jaw discrepancies, dental compensation, and surgical correction. Cohen says that all Class II treatments fall in these categories. Class II therapies depend upon the skeletal disharmony, the patient’s growth potential, and the necessity for extractions.

Mihalic, et al, suggest that for adult Class II patients, there are only two possible treatment approaches: camouflage orthodontics, consisting of extracting two maxillary premolars and retracting the maxillary anterior teeth to improve the occlusion and facial esthetics or to perform orthognathic surgery to correct the skeletal discrepancy.Excessive maxillary gingival displays can be due to skeletal, dentoalveolar, or soft tissue imbalances. The skeletal type is caused by excessive vertical maxillary growth and is usually found in vertical growing patients. The use of mini-implants as temporary anchorage devices has been of great value in the treatment of these Class II patients.

The purpose of this article is to present the treatment of a Class II division 1 adult patient with excessive maxillary gingival display associated with a skeletal malocclusion that was treated with maxillary first premolar extractions and TADs to reinforce anchorage of the posterior segments and to intrude the maxillary anterior teeth.

Diagnosis and etiology

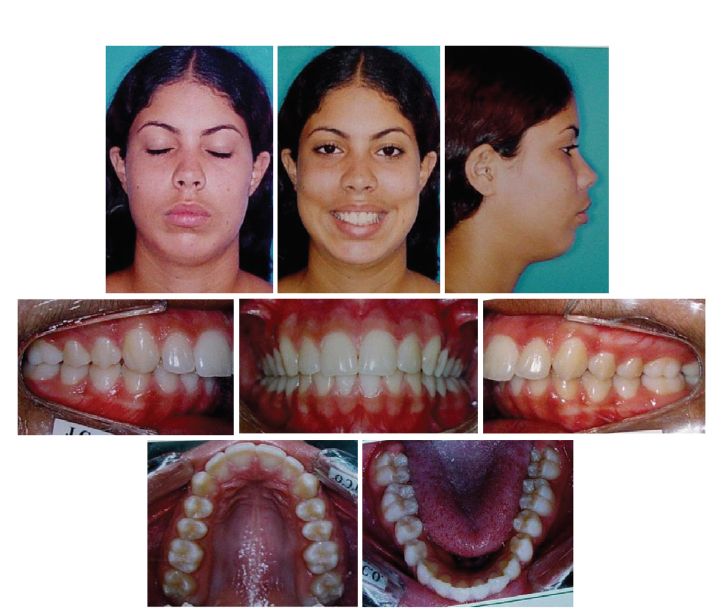

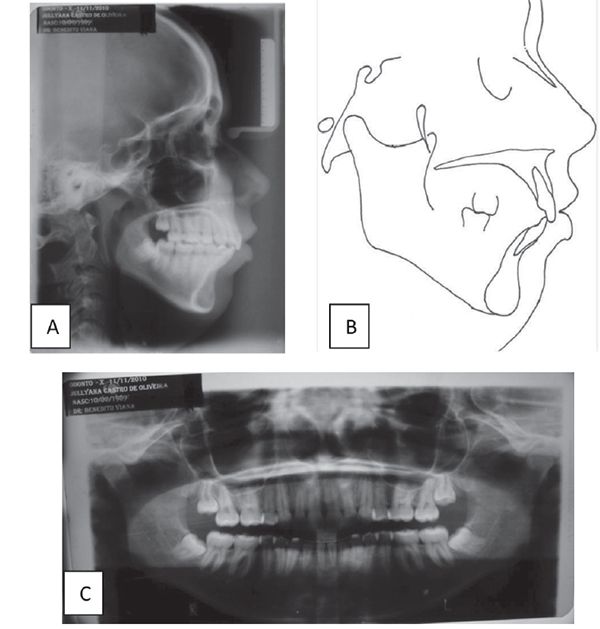

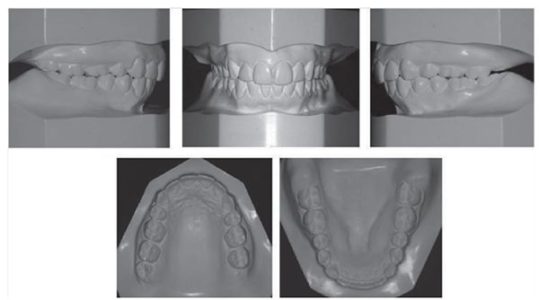

A 21-year-old woman presented for an orthodontic consultation with chief complaints of “protrusive lips and a gummy smile.” The extraoral clinical examination showed good facial symmetry, lack of lip seal, convex profile, excessively proclined and extruded maxillary incisors, excessive maxillary gingival display, and a retruded mandible. Intraorally, there was a severe Class II division 1 malocclusion, deep overbite (6 mm), an overjet of 8 mm, and good oral hygiene. She had no relevant medical history or previous orthodontic intervention. The patient’s speech was normal (Figure 1).

During opening and closing mandibular movements, there was no mandibular deviation. No sign of temporomandibular derangement such as clicking or crackling, or pain in the temporomandibular joints was evident.

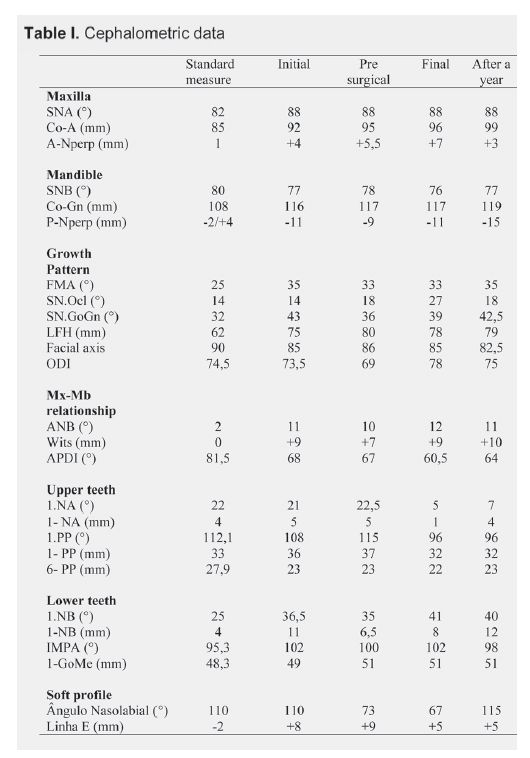

Cephalometrically, there was maxillary protrusion and mandibular retrusion associated with excessive vertical growth. The maxillary incisors were labially inclined and extruded, and the mandibular incisors were proclined (Figure 2, Table I).

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives consisted of correcting the protracted maxilla, the occlusal anteroposterior relationship, i.e., the overjet and overbite, the excessive maxillary gingival display, and obtaining a passive lip seal, which would improve the patient’s facial esthetics.

Treatment alternatives

An orthodontic-surgical approach, consisting of mandibular and chin advancement associated with superior repositioning of the maxilla, was proposed as a first treatment option. This treatment option would fulfill all the treatment objectives. As a second option, extraction of two maxillary first premolars to allow retraction of the anterior maxillary teeth associated with intrusion of these teeth to correct the excessive maxillary gingival display, using mini-implants as anchorage, was proposed. This option would allow correction of most of the problems, but would not correct the mandibular retrusion. The patient did not elect the surgical procedures and chose the second option.

Treatment progress

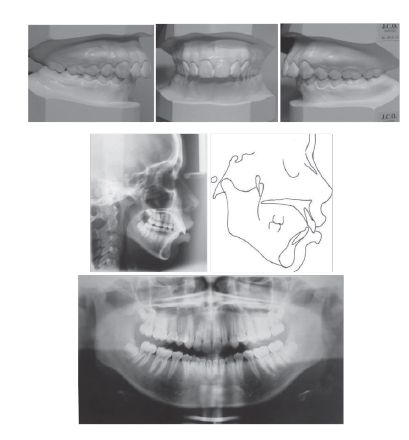

The malocclusion was treated with preadjusted 0.022 inch slot edgewise appliances (Roth prescription). Leveling and alignment began with 0.014 inch followed by 0.016 inch nickel-titanium arch wires and progressed to 0.018, 0.020 and 0.019 x 0.025-inch stainless steel arch wires. After leveling and alignment (10 months), the maxillary first premolars were extracted and mini-implants (1.8 mm x 8 mm C-implant) were inserted bilaterally between the maxillary first molars and second premolars to provide skeletal anchorage. Another mini-implant (1.4 mm x 6 mm – Dentos, Daegu, South Korea) was inserted between the roots of the maxillary central incisors to intrude the anterior maxillary teeth. The anterior segmental retraction was accomplished with rectangular stainless steel arch wires (0.019 x 0.025 inch), with nickel-titanium closed coil springs activated from the hooks soldered distally to the canines directly to the mini-implants, with a force of 150g. Concurrently, a nickel-titanium coil spring was also activated between the arch wire midline and the anterior mini-implant to intrude the maxillary anterior teeth. After 20 months, the posterior mini-implants were removed to allow maxillary posterior teeth protraction and interdigitation, which lasted 4 months. Multiloop edgewise arch wires were used with vertical intermaxillary elastics for 2 months (Figure 5). Active treatment time was 26 months. The patient was retained with a maxillary Hawley retainer and a mandibular bonded canine-to-canine retainer.

Results

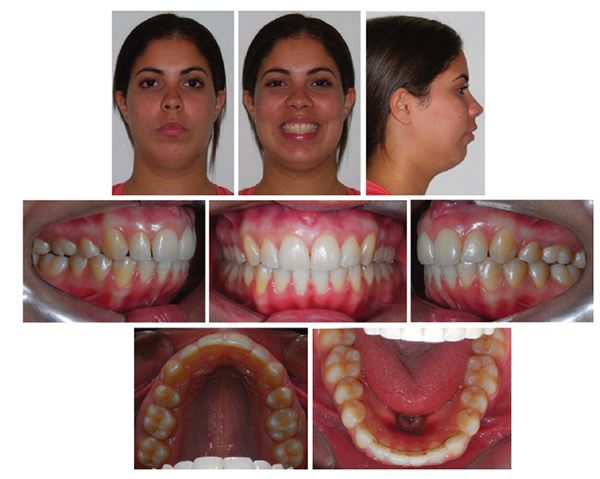

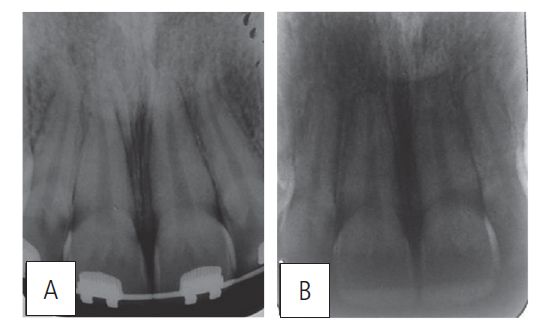

The extraoral photographs show good lip sealing, decreased maxillary gingival display, and improved facial profile, although with a retrognathic mandible and convex profile. The intraoral photographs and dental models show Class I canines and Class II molars on both sides, and normal overbite and overjet (Figure 6). Good root parallelism was obtained (Figure 7). Cephalometrically, there was palatal tipping and intrusion of the maxillary incisors and labial tipping of the mandibular incisors (Table I). There was lower lip retrusion and an increase in the nasolabial angle. The patient was satisfied with her occlusion and facial esthetics, and 1 year later, she displays good stability (Figures 8, 9, and 10).

Discussion

Mini-implants used as orthodontic anchorage offer high potential for favorable results and many treatment options, because they reduce the need for patient compliance. TADs are well indicated for intrusion of teeth, because it is possible to apply continuous and light forces, which can reduce apical root resorption often associated with intrusive movements.

Excessive gingival display associated with severe Class II division 1 malocclusion compromises facial esthetics, especially when associated with mandibular retrognathism and vertical maxillary excess. Orthognathic surgery is considered a preferred modality of treatment for this type of patient with mandibular advancement, superior repositioning of the maxilla or a combination of both, which will improve the patient’s facial harmony.9 However, many patients are unwilling to undergo surgery, and in these cases, orthodontic camouflage is the best alternative, as in the current case. Lately, TADs have been used for treating Class II, division 2 malocclusions with deep overbite. This procedure is simple and requires minimal patient compliance. Although the profession still lacks concrete evidence that this type of incisor intrusion remains stable over time, we can now intrude anterior teeth free from the past restrictions when molar extrusion was the only option for treating deep overbite.

Camouflage orthodontic therapy consists of dental compensations through extractions of premolars and en masse retraction followed with incisor intrusion in order to reestablish better horizontal and vertical dental occlusion and facial esthetics, without correcting the skeletal problem. In these patients, it is considered important that the orthodontist explain to the patient the possibilities of treatment, taking into consideration the esthetic and functional expectations that it features.

Correction of the excessive maxillary gingival display cannot be performed with a high pull headgear in adult patients because these appliances have disadvantages, such as their unesthetic appearance, undesirable intermittent forces, lack of growth, and dependence on patient cooperation. Nor could Burstone´s segmented technique be used to perform anterior intrusion, because the side effects of extrusion of the posterior region would worsen the patient´s vertical pattern. This patient’s maxillary incisors were palatally tipped and retruded (Table I). Others have previously demonstrated this technique.

Excessive gingival displays due to a skeletal discrepancy can be treated with a combination of TADs and periodontal surgery13, and in growing patients, high pull headgears associated with periodontal surgery have been reported.14 The method of incisor intrusion with skeletal anchorage was first introduced by Creekmore and Eklund15 and was recently reported by Ohnishi, et al.16 To ensure maximal retraction and prevent excessive lingual tipping of the anterior teeth, Shu, et al,7 placed a compensatory curve in the maxillary arch wire, which could counteract the deformation of arch wire, provide torque control on the anterior teeth, and assist in correcting the deep overbite. Kaku, et al,17 inserted the miniscrews in the maxillary bone above the lateral incisors root apices because the patient had sufficient space for miniscrew placement superior to the apices.

Our decision to insert a mini-implant between the roots of the maxillary central incisors was to control the torque, avoid contact of the roots with the lingual cortical bone during the anterior en masse retraction, and achieve enough intrusion to correct the excessive gingival display.

We consider this procedure as easier and more effective. Our patient had an excessive maxillary anterior gingival display, and the posterior teeth were in vertical positions. With this type of patient, an excessive gingival display can be corrected efficiently by intrusion of maxillary incisors with minimum root resorption (Figure 11). Therefore, we planned to intrude the maxillary incisors with miniscrews, which could provide a desirable improvement of the smile and facial profile without correcting the mandibular retrusion.

Our patient had a slight decrease in SNB; however, there was only a small change in FMA and in the lower facial height (LFH), which demonstrated little clockwise rotation of the jaw (Table I). The records after 12 months of the end of treatment show occlusal stability, correction of the excessive gingival display, good canine relationships, and satisfactory facial appearance (Figures 9 and 10).

Conclusion

Mini-implants can provide stable skeletal anchorage during maxillary anterior teeth retraction concomitantly with intrusion of these teeth. Therefore, this approach offers an excellent treatment alternative to an orthodontic-surgical technique for patients unwilling to undergo surgery to correct a Class II maxillary dentoalveolar protrusion with an excessive gingival display.

References available upon request.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores