Drs. Francesca Scilla Smith and Larry W. White explore the role of canines in orthodontic treatment and how one universal method of treatment may be counterproductive.

Drs. Francesca Scilla Smith and Larry W. White discuss centric occlusion, centric relation, and the role of canines

Canines

Prior to 1958, when Dr. Angelo D’Amico1-6 published his six articles on the role of canines in functional occlusion, most dental restorative practitioners ascribed to the group function theory that arranged the teeth in a balanced occlusion with group function on the working side. D’Amico challenged this prevailing application by showing how the canines could be instrumental in guiding the occlusion in lateral excursions7,8 by having the osseous support of dense compact bone9 and the longest roots10 of the dentition to tolerate lateral forces better than other posterior teeth. One additional advantage discovered for canine-protected occlusion was that fewer muscles activated during eccentric movements than when posterior teeth contact.11

D’Amico’s theory has had an enormous influence among gnathologists and sub-sequently dental faculties and caused some to allege that without canine protected occlusion (CPO), orthodontic patients would have a predisposition to TMD as well as treatment relapse.12,13 Still balanced occlusion seems to appear often in people with Class I and optimal occlusions.14 Another study has revealed that CPO and group function rarely exist in a pure form, and that balanced occlusion appears as a general rule.15 McNamara16 has perhaps summarized the controversy of occlusion by pointing out that several acceptable functional occlusal systems can exist harmlessly; and that although ortho-dontic therapy tries to achieve a stable occlusion, the failure to achieve a specific, gnathological goal doesn’t predispose patients to TMD, discomfort, or dysfunction. Certainly, occlusal interferences need to have reduction when they cause tooth mobility, a vibratory sensation, or deflection in mandibular movements; but so many occlusal variations exist. A prescription for one universal schematic seems pointless and even counterproductive.17

Centric relation

The classical definition of centric relation (CR) was the most retruded, posterior, and superior position of the condyle in the glenoid fossa, and this formed the raison d’être for gnathologists, prosthodontists, and dentists generally for decades. In 1995,18 the Academy of Prosthodontists changed this definition and, for the most part, defined the normal condylar position as being in the most superior and anterior part of the glenoid fossa. Some have implied that the centric occlusion (CO) and centric relation (CR) should be coincident, but that notion has not found corroborating evidence.19

Neither the classic definition nor the newly minted definition of CR had any scientific grounding but was entirely arbitrary.17 Even as far back as 1969 with telemetry studies,20-22 researchers discovered entire occlusions restored to a retruded CR still functioned around 2 mm forward of that condylar position. Many people have an anterior slide and can prove it by positioning the tongue on the soft palate, which puts the condyle in its most retruded position and then brings the teeth together. An anterior slide of 1 mm-3 mm is quite common and apparently has a muscular component as well as dental. To presume that there is one particular CR position for an entire population rather than a range of possible positions begs credulity.

One can never know if D’Amico intended to confer sainthood on the canine and make it sacrosanct, but that has certainly been the effect — to the extent that dentists will seldom honor an orthodontist’s request for the removal of canines, even those severely impacted with little or no likelihood of ever occupying an ideal occlusal position without serious periodontal compromise.

The tergiversational decision by dental faculties, dentists generally and specialists specifically have limited the interest in even discussing the merits of this feature of the dental canon, much to our professional peril and to our patients.

The sanctity of the canine needs serious reconsideration by the profession for the good of our patients.

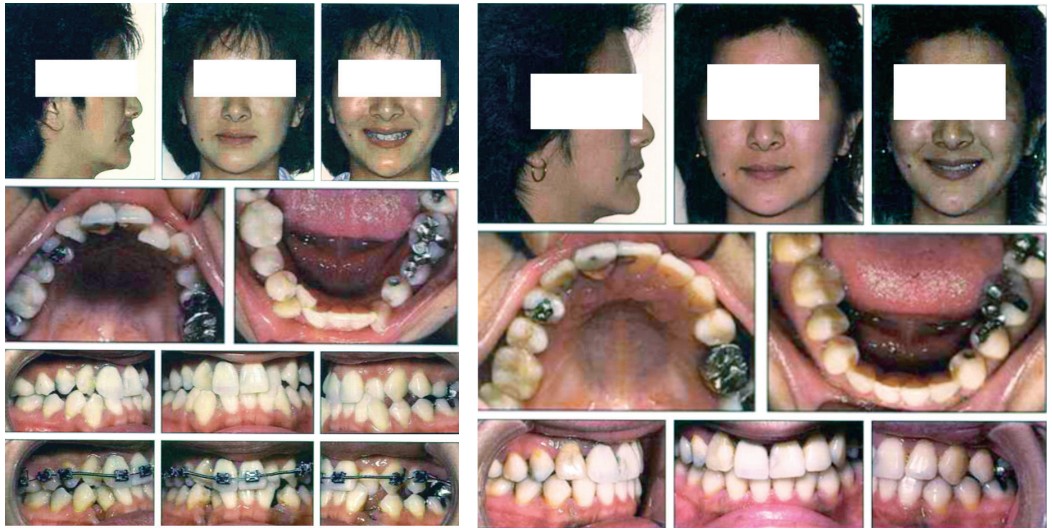

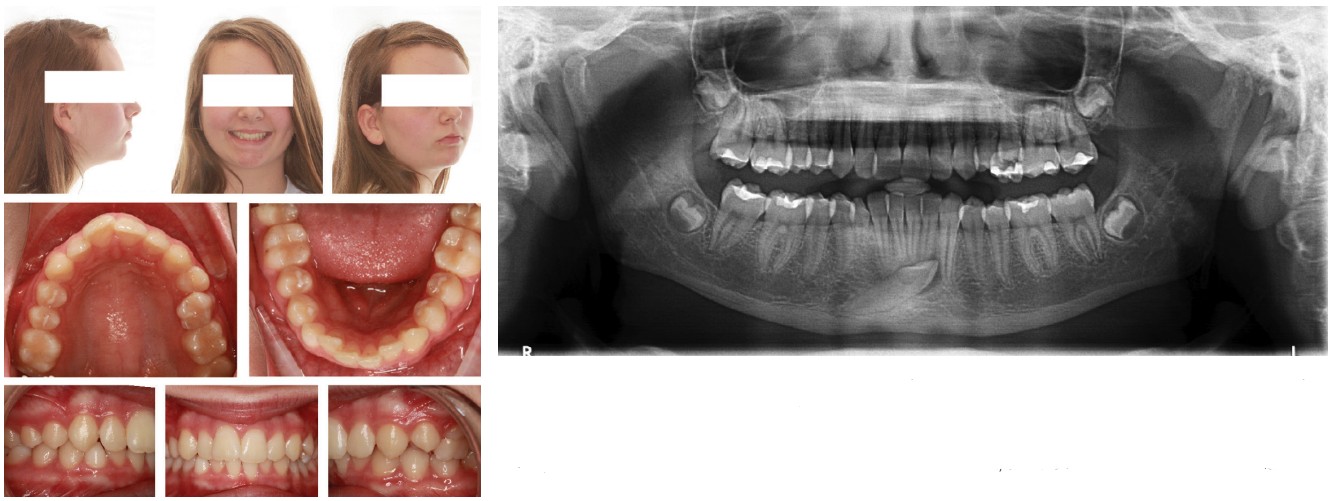

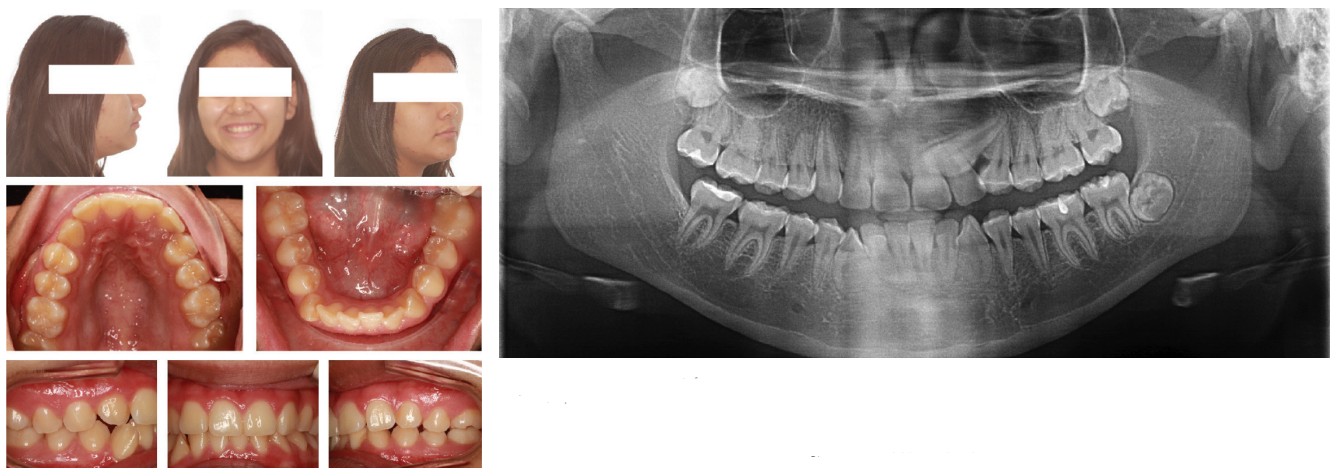

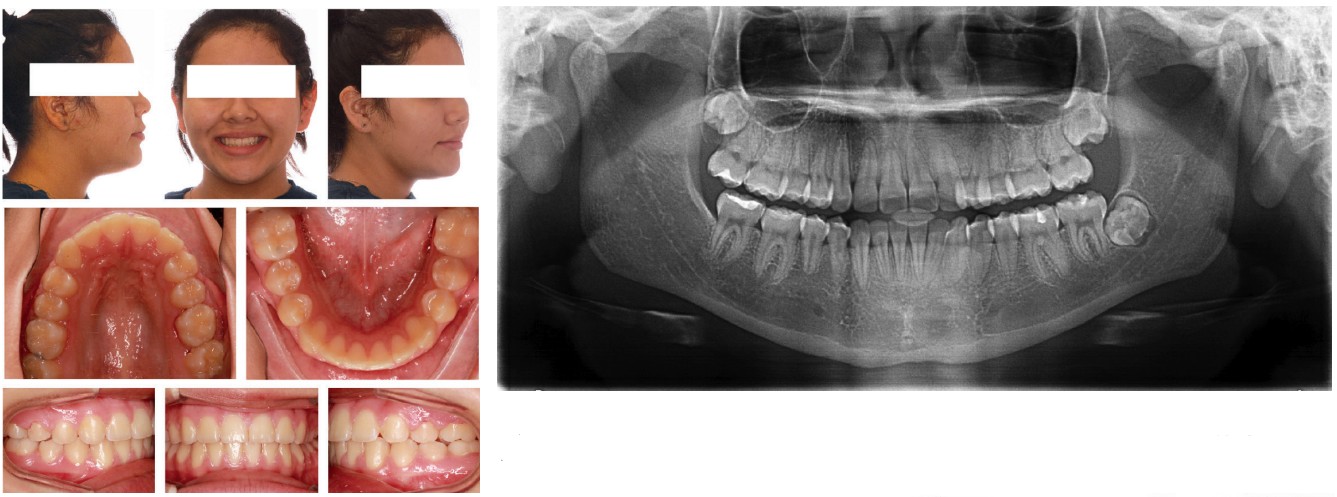

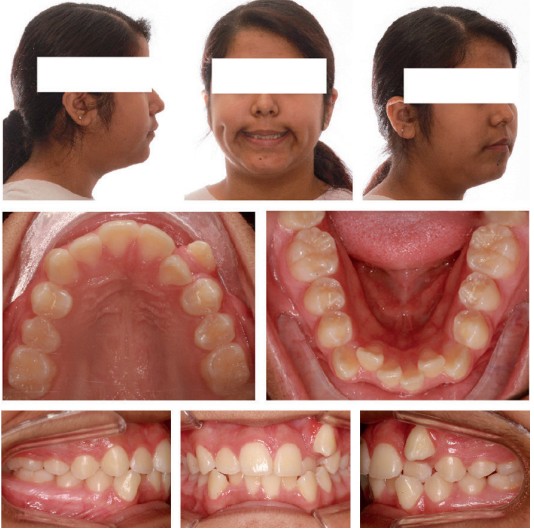

There are reports of successful occlusal, esthetic, and orthodontic outcomes with the extraction of canines, and even a recent perception study found no difference in smile attractiveness between maxillary canine extraction and premolar extraction patients.23-26 An assessment tool — used by Ericson and Kurol27 and used by Sigler, et al.,28 to evaluate the severity and/or morbidity of erupting and aligning of impacted maxillary canines — has proven useful in the decision-making regarding impacted maxillary canines. Rinchuse, et al.,29 developed an orthodontic informed consent that identified the potential morbidity associated with the alignment of impacted teeth, which the American Association of Orthodontists accepted as a supplement to their consent form.

I include below some of the patients with successful canine extraction therapies to illustrate that D’Amico’s idea of the canine protected occlusion has less universal appeal and usefulness than he originally envisioned and intended (Figures 1-5).

Conclusion

Jacobs30 averred long ago that a well-positioned tooth should never be removed to make space for a poorly positioned one (Figure 6), while Stewart, et al.,31 discovered that aligning impacted maxillary canines took longer, which has consequences beyond properly aligning the canine such as loss of molar anchorage, compromised periodontium, and root resorption of adjacent teeth. Bowman32 has suggested that in many instances to do something for the simple reason that we can doesn’t mean that we should. My personal experience has been such that I wish someone had offered the idea during my training that some impacted canines can and should be removed to avoid morbidity, the burden of extra and unnecessary care, longer treatment, more expense, more trauma, and more uncertainty about the outcome. Of all that comprises the dental canon, the sanctity of the canine needs serious reconsideration by the profession for the good of our patients.

The role of canines is also a focus of this CE: “Palatally displaced canines — is there a way to prevent impaction of these teeth?” Take the quiz and obtain 2 CE credits! https://orthopracticeus.com/ce-articles/palatally-displaced-canines-way-prevent-impaction-teeth/

- D’Amico A. The canine teeth: normal functional relation of the natural teeth of man: No. 4. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1958;26(5):175-182.

- D’Amico A. The canine teeth: normal functional relation of the natural teeth of man: No. 2. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1958;26(2):49-60.

- D’Amico A. The canine teeth: normal functional relation of the natural teeth of man: No. 3. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1958;26(4):127-142.

- D’Amico A. The canine teeth: normal functional relation of the natural teeth of man: No. 5. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1958;26(6):194-208.

- D’Amico A. The canine teeth: normal functional relation of the natural teeth of man: No. 6. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1958;26(7):239-241.

- D’Amico A. The canine teeth: normal functional relation of the natural teeth of man; No. 1. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1958;6(1):6-22.

- Grosfeld O, Czarnecka B. Musculo-articular disorders of the stomatognathic system in school children examined according to clinical criteria. J Oral Rehabil. 1977;4(2):193-200.

- Magnusson T, Carlsson GE, Egermark-Eriksson I. An evaluation of the need and demand for treatment of craniomandibular disorders in a young Swedish population. J Craniomandib Disord. 1991;5(1):57-63.

- Swanljung O, Rantanen T. Functional disorders of the masticatory system in Southwest Finland. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1979;7(3):177-182.

- Dibbets JMH. Juvenile temporomandibular joint dysfunction and craniofacial growth. A statistical analysis. 1977; Rijkesuniversiteit. Groningen, the Netherlands.

- Hansson T, Nilner M. A study of the occurrence of symptoms of diseases of the TMJ, masticatory musculature, and related structures. J Oral Rehabil. 1975;2(4):313-324.

- Roth RH. The maintenance system and occlusal dynamics. Dent Clin North Am. 1976;20(4):761-788.

- Roth RH, Rolfs DA. Functional occlusion for the orthodontist. Part II. J Clin Orthod. 1981;15(2): 100-123.

- Turk DC, Rudy TE, Kubinski JA, Zaki HS, Greco CM. Dysfunctional patients with temporomandibular disorders: evaluating the efficacy of a tailored treatment protocol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):139-146.

- Woda A, Vigneron P, Kay D. Nonfunctional and functional occlusal contacts: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;42(3):335-341.

- McNamara JAJ, Seligman D, Okeson J. Occlusion, orthodontic treatment, and temporomandibular disorders: a review. J Orofac Pain. 1995;9(1):73-89.

- Rinchuse DJ, Kandasamy S, Sciote J. A contemporary and evidence-based view of canine protected occlusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(2):90-102.

- Glossary of prosthodontic terms. J Prosthet Dent. 1995; 94(1):10-92.

- Rinchuse DJ. A three-dimensional comparison of condylar position changes between centric relation and centric occulusion using the mandibular position indicator. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;107:319-328.

- Pameijer J, Glickman I, Roeber F. Intraoral occlusal telemetry: 3. Tooth contacts in chewing, swallowing and bruxism. J Periodontol. 1969;40(5):253-258.

- Glickman I, Martigoni M, Haddad A, Roeber FW. Further observation on human occlusion monitored by intraoral telemetry (abstract 612). International Association of Dental Research. 1970; 201.

- Pameijer JH, Brion M, Glickman I, Roeber FW. Intraoral occlusal telemetry. V. Effect of occlusal adjustment upon tooth contacts during chewing and swallowing. J Prosthet Dent. 1970;24(5):492-497.

- Creekmore, T., Where teeth should be positioned in the jaws and how to get them there. J Clin Orthod. 1997;31(9): 586-608.

- Mirabella D, Giunta G, Lombardo L. Substitution of impacted canines by maxillary first premolars: a valid alternative to traditional orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143(1):125-133.

- Thiruvenkatachari B, Javidi H, Griffiths SE, Shah AA, Sandler J. Extractin of maxillary canines: Esthetic perceptions of patient smiles among dental professionals and laypeople. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152(4):509-515.

- Al Shhab MK, Mansour EE, El-Beialy AR, Mostafa YA. Unusual extraction combinations in patients with impacted maxillary canines. J Clin Orthod. 2019;53(10):603-610.

- Ericson S, Kurol J. Radiographic examination of ectopicall erupting maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91(6):483-492.

- Sigler LM, Baccetti T, McNamara JA Jr. Effect of rapid maxillary expansion and transpalatal arch treatment associated with deciduous canine extraction on the eruption of palatally displaced canines: A 2-center prospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139(3):e235-e244.

- Rinchuse DJ, Jerrold L, Rinchuse DJ. Orthodontic informed consent for impacted teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(1):103-104.

- Jacobs SG. Localization of the unerupted maxillary canine: how to and when to. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115(3):314-322.

- Stewart JA, Heo G, Glover KE, et al. Factors that relate to treatment duration for patients with palatally impacted maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119(3):216-225.

- Bowman SJ. One-stage versus two-stage treatment: Are two really necessary? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113(1):111-116.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Francesca Scilla Smith, DDS, MS, was born and raised in Arezzo, Italy. She graduated summa cum laude at the University of Florence Dental School and obtained her orthodontic degree from Nova Southeastern University College of Dental Medicine in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with a master thesis on conventional and digitally driven indirect bonding. Dr. Scilla Smith practices orthodontics in Dallas, Texas.

Francesca Scilla Smith, DDS, MS, was born and raised in Arezzo, Italy. She graduated summa cum laude at the University of Florence Dental School and obtained her orthodontic degree from Nova Southeastern University College of Dental Medicine in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with a master thesis on conventional and digitally driven indirect bonding. Dr. Scilla Smith practices orthodontics in Dallas, Texas. Larry W. White, DDS, MSD, FACD, is a graduate of Baylor Dental College and Baylor Orthodontic Program and now has an orthodontic practice in Dallas, Texas.

Larry W. White, DDS, MSD, FACD, is a graduate of Baylor Dental College and Baylor Orthodontic Program and now has an orthodontic practice in Dallas, Texas.