Dr. Rohit C.L. Sachdeva explores a proactive, quality-focused approach to orthodontics

Abstract

Abstract

The current approach to orthodontic care is largely error-prone and, therefore, reactive. Such error-ridden care practices negatively impact the quality of the care delivered. In this article, the author discusses his manifesto for BioDigital orthodontics, a proactive, quality-focused approach to orthodontics. The principles and practice of patient-centered care, patient safety, and clinical effectiveness as they relate to the practice of quality care are presented.

Introduction

Quality orthodontic care is a commodity. Why? Because almost all doctors believe they provide quality care to their patients. The reason this myth prevails is that the definitions of quality practices and metrics remain vague at best.1 Currently, said practices measure the spatial relationships of the dentition and are not rooted in scientific evidence in terms of their clinical or physiological significance (such as blood pressure or body temperature) thus diminishing their validity as effective measures of well-being. Also, these measures are not universally accepted by the specialty or the profession of dentistry at large. In this way, the clinician acts as both judge and jury, rubber-stamping an autonomous verdict of “all looks well; no harm done” in the treatment delivered to patients. Such behavior has a ripple effect within the orthodontic care ecosystem. For instance, said behavior blunts the patient’s understanding of quality care, diminishing the value of the genuine quality-driven orthodontist; hence, the rise of the “nonexpert expert,” the dentist orthodontist, laboratory technician-orthodontist, and more recently, the consumer-orthodontist.

“Be a yardstick of quality.

Some people are not used

to an environment where

quality is expected.

— Steve Jobs

The ambiguous definition of quality care has facilitated the proliferation of market-driven orthodontics. Practices measure their success on the basis of business metrics, such as profit and production, rather than patient-care outcomes.

This is not all bad news. The recognition of these deficiencies provides us with the springboard upon which to explore opportunities to better our specialty and reinforce the covenant of trust between the specialist and her patient.

So how do we cure our ills? First, we must redefine our metrics and build the engine that allows us to practice quality care. This requires improvements in both the relational and functional components of our care giving. Henry Ford described this notion best when he said, “Quality means doing it right when no one is looking.” We must embrace and commit to a new cultural fluency that fosters patient centeredness, patient safety, and clinical effectiveness.2

Patient-centered care

Past and present

Historically, a paternalistic, hierarchical model defined the doctor-patient relationship. The doctor “knew best,” effectively silencing the voice of the patient. Recently, however, the consumer-driven orthodontic care model has redefined the doctor-patient relationship, establishing a contractual relationship between buyer (patient) and seller (doctor).3 In this setting, the buyer “knows best” and pays for her wants, not her needs. The buyer’s commonly misinformed expectations of care now muffle the voice of the well-intentioned, evidence-driven doctor.

“Ordo ab chao

(order out of chaos)

Both of these models of doctor-patient relationships are flawed, warranting a more balanced doctor-patient relationship.

What exactly is patient-centered care?

Patient-centered care is not just about giving patients whatever they want or educating them about their needs. It is, first and foremost, about the doctor establishing trust and credibility with the patient.4 It is about the orthodontist and care team showing empathy and humanity in embracing the patient as a person, not a case; a patient named John who is afflicted with a malocclusion, not a case labeled a Class 1 malocclusion.

Patient-centered care means the orthodontist recognizes he/she is a guest in the patient’s life.5 In a patient-centered practice, the patient is aware of and understands his/her “bill of rights.”6 Patient-centered care teams value the patient’s opinion, engage in active listening and shared decision-making with the patient, and establish rapport with the patient in addressing care needs. Said care teams respect the patient’s ability to assert his or her individuality. Patient-centered care also means complete transparency; the care team offers full, unbiased information about the options, benefits, and risks of any care measures planned.

Potential disconnects between the voice of the doctor and that of the patient are best resolved using a casuistic approach to clinical decision-making. This model considers patient values, backgrounds, and preferences alongside empirical evidence, experiential evidence, pathophysiological rationale, and system features.7

As such, orthodontic patient-centered care practices carry the banner of a “patient of one.”5

Patient safety

Past and present

Conventional orthodontic care has been and continues to be craft-based and reactive. We practice “wayfaring” orthodontics and manage patient care through the rear-view mirror. This model of care provides fertile soil for the seeding and proliferation of error-associated events.

It is important to note that human error is a consequence, not a cause. Human error is the product of a chain of causes in which precipitating psychological factors include lapses in attention, forgetfulness, misjudgment, and preoccupation. Errors are generally described by what I call the 8 M’s:

- miscommunication

- misunderstanding

- misdiagnosis

- misplanning

- mismanaging

- misdesigning

- misprescribing

- misadministering.

Errors are commonly “long tail” in nature and are often the last and least manageable links in the chain. As such, errors are recognized in the finishing stage of orthodontic treatment, a stage in treatment in which the clinician intends to correct for errors and the patient, accordingly, is admitted into the intensive care unit.8

The finishing stage is challenging for both the patient and doctor. If we were to enter the patient’s mind during the finishing stage, we might encounter a patient who suffers from anxiety and orthodontic exhaustion. The patient falsely believes her treatment to be complete and now must undergo additional treatment. Candidly put, the patient is burnt out. From the clinician’s perspective, much treatment remains to be done. The clinician, too, is anxious as he/she wrestles with the professional commitment to properly treat the patient, a patient who is now half-heartedly committed to treatment. At this point in treatment, patient adherence to the doctor’s recommendations decreases, the timing of the patient’s appointments becomes erratic, and the doctor’s skills are put to the test. The finishing stage is therefore disruptive to both the patient’s expectations of care and lifestyle, the clinician’s mindset and schedule, and the orthodontic practice’s operations.

The very fact that we accept finishing as a stage in patient care suggests that we condone a system that allows for error propagation. This practice must be prevented, or at very least, contained.

Another shortfall in our practice model is that we lack both intrapractice and system-wide transparency. We neither report nor disclose error; failure is merely paid lip service, not action. If we do not document error, we cannot analyze, learn, and subsequently improve upon our ways. Given our avoidance of error reporting, the waters always appear calm; nothing appears broken, so we convince ourselves that there is nothing to fix. Thus, our modus operandi continues with little recognition of the undermining forces that affect our quality of care. Such an error-prone environment comes at a substantial cost to both the patient and doctor and also delays care.

Unfortunately, failures in outcomes occur more often than not. (One just needs to see transfer patients to appreciate the extent of this problem). Failures in outcomes are commonly attributed to biological and psychosocial factors, such as poor patient growth or cooperation. The patient bears the brunt of responsibility for a less than desirable result, and the doctor remains unaccountable for her probable misaction. If the doctor is “brave enough” to report failure, she does so at the risk of her reputation and potential litigation.

We have yet to mature into a blame-free culture and recognize that humans commit errors. Systems, processes, and technology must be appropriately used by a skilled care team to prevent or arrest the propagation of errors.

What exactly is patient safety?

Patients almost entirely depend upon the skills and professional judgment of the orthodontist and his/her team to receive the best in care. The overarching goal of an orthodontic practice that subscribes to patient safety is to protect patients from harm. This requires building a trustworthy system for the delivery of orthodontic care.

Patient safety is the prevention of the errors that result in unwanted and adverse effects. It is also concerned with minimizing the incidence of and maximizing the recovery from spurious or adverse events. Errors must be continuously reported, analyzed, and communicated to all team members in an ongoing effort to error-proof the care delivery system.

The practice of patient safety is grounded in the principles and practice of safety/reliability science.9

Reliability refers to failure-free operation over time. Practically speaking, reliability is the ability of a process, procedure, or service to perform its intended function in the required time under existing conditions. Reliability is measured by dividing the number of actions to achieve the intended result by the total number of actions.10

Orthodontic practices must adopt the principles of High Reliability Organizations (HRO). An HRO is designed to minimize danger by balancing effectiveness, efficiency, and safety. An HRO preserves a culture of system-wide transparency and error-reporting. An HRO is both proactive and generative in its actions and also shares the cultural framework of learning organizations.

Roberts and Bea note, “More specifically HROs actively seek to know what they don’t know, design systems to make available all knowledge that relates to a problem to everyone in the organization, learn in a quick and efficient manner, aggressively avoid organizational hubris, train organizational staff to recognize and respond to system abnormalities, empower staff to act, and design redundant systems to catch problems early.”11

The success of an HRO is partly based on its ability to stay mindful. An HRO promotes five mindful practices to manage safety, including12:

- Preoccupation with failure. Team members must incessantly seek ways to error-proof the system and mitigate risk.

- Reluctance to simplify. Simple processes are strived for, but oversimplified explanations for error are avoided. Analyses of the root causes of error are performed.

- Sensitivity to operations. Team members must be consistently mindful of noting and preventing risks.

- Commitment to resilience. Team members are trained to 1) anticipate or know what to expect 2) pay attention or know what to look for, and 3) respond or know what to do.

- Deference to expertise. Each and every team member carries an equal voice in calling out violations or reporting errors or adverse events.

The baseline of an HRO’s core processes operates correctly 99% of the time. In healthcare, the baseline of core processes is defective 50% of the time, for 50% of patients receive recommended care.

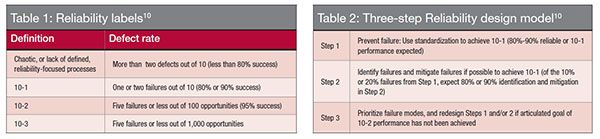

Healthcare practices are less reliable than industrial practices; as a result, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) recommends that healthcare organizations should focus on process reliability as a first step on the road to safe care before focusing on the mindful practices of an HRO. (I would tend to agree that orthodontics take the same approach.) Baseline performance reliability for non-catastrophic processes in healthcare is currently said to be less than 80%. What does this mean? The IHI has established a measure termed “‘failure rate’ (calculated as 1 minus reliability, or ‘unreliability’) as an index, expressed as an order of magnitude.”10 Thus, 10-1 means approximately one defect (error) per 10 process opportunities. If 10 brackets were bonded on a patient, and one of them was misplaced, the defect rate would be 10-1; 10-2 is approximately one defect per 100 process opportunities.10

I believe there will always be some of us who have a passion for giving their best. And quite frankly, if there aren’t, then no process will save us.

— Tony Cusano, MD

Recognizing that the strict adherence to this formula may pose difficulties in interpreting unsafe or error-prone practices, the IHI developed a broader classification to evaluate the failure rate (Table 1). As clinicians can see, the rate of two defects per 10 process opportunities represents less than 80% success; this measure indicates a chaotic or unreliable process. Translating this measure into the world of orthodontics suggests that the incorrect placement of just two brackets on 100 teeth (five patients) would be classified as an unreliable process. We know our defect rate is, unfortunately, much higher, begging the need for reliable processes in orthodontics.

The IHI’s three-step reliability design model offers a path to consider in building safer care processes (Table 2).

With a sense of urgency and commitment, the profession of orthodontics needs to embark upon a journey to develop and implement minimal error, ultra-safe practices.

With a sense of urgency and commitment, the profession of orthodontics needs to embark upon a journey to develop and implement minimal error, ultra-safe practices.

Clinical effectiveness

Past and present

Reactive care orthodontics encourages a “do first, think later” mentality. Clinically, this translates to “let’s slap on the braces and see what happens.” This practice encourages epistemic complacency.

Diagnosis, care design, and planning provide little value to the reactive care practitioner in her management of patient care. The “intelligence manufactured” into the appliance overrides the clinician’s cognitive tools of reason, judgment, and sense making. Evidentiary practices are reserved for the ivory tower and find little use for the wet finger, reactive-care orthodontist.

Unfortunately, unscientific, dogmatic care protocols primarily designed to maximize the use of latest and best “smart” appliances are promoted by industry-appointed thought leaders. It then follows that the influencers who create the loudest echo chamber are responsible for defining the standard of care. As a result, the doctor becomes entangled in the web of “a la mode” or market-driven orthodontics, distancing even further from science and value-based practice.

Recently, the orthodontic industry has adopted the practice of recruiting patients, or care customers, to promote products through the powerful channel of social media.13, 14 To appeal to a wider audience, much of the messaging is emotional rather than evidence-driven. This mode of communication commonly results in a misinformed patient who attempts to drive his care with little regard for professional advice.

The combination of the reactive care model and the strong influence of industry and its appointed thought leaders has channeled the practice of orthodontics into a cafeteria or standardized, mass manufacturing product- and profit-driven approach. The orthodontic enterprise is populated with misguided doctors and misinformed patients.

The practice of orthodontics needs to reframe itself. Another cultural pill it needs to be prescribed is that of clinical effectiveness.

Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.

— Mark Twain

What is clinical effectiveness?

Clinical effectiveness is defined as “the application of the best knowledge, derived from research, clinical experience, and patient preferences to achieve optimum processes and outcomes of care for patients. The process involves a framework of informing, changing, and monitoring practice.”15

Clinical effectiveness is concerned with demonstrating continual improvements in quality and performance. The properties of clinical effectiveness follow15:

- Doing the right thing (evidence-based practice requires that decisions about patient care are based on the best available, current, valid, and reliable evidence)

- In the right way (developing a care team that is skilled and competent to deliver the care required)

- At the right time (accessible services provide treatment when the patient needs them)

- In the right place (location of care services)

- Resulting in the right outcome all the time (clinical effectiveness)

Clinical effectiveness is about improving the “total care experience” of the patient. It requires thinking critically about what the care team does, questioning whether the team is achieving the desired result, and making necessary changes to unreliable practices. This can only be accomplished if the doctor and her care team are committed to measuring the quality of care. Continuous improvement methodologies such as the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle may be used to effect improvement.16 Measures from such initiatives are critically evaluated to seek evidence of what is effective in order to improve a patient’s care and experience.

The doctor and the care team should always be attentive and respectful of the patient’s care preferences. Patient-reported outcome programs such as Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROM) and Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREM) should be implemented to directly seek the voice of the patient in care improvement initiatives.17 Also, patient literacy programs to better educate patients in evaluating the quality and source of healthcare information and judge doctor skills should be considered.

Never underestimate the power of a small group of committed people to change the world. In fact, it is the only thing that ever has. — Margaret Wheatley

Conclusions

Our profession is at a crossroads. We have a unique opportunity to better patient care by implementing creative solutions.

Change can only succeed if we act with a sense of purpose, purpose defined by the values and the belief system we adopt — our culture. We need to acculturate ourselves to a “patient first” care model. This requires that we migrate to a platform that supports mindfulness, is proactive in its practices, and is performance based.

The orthodontic practice of the future will be designed around what I term the E. A. A. R. model:

- Empathy for patients

- Anticipate issues to prevent problems

- Attention to processes and procedures

- Reflective thinking to continuously improve

Four important points must be noted. First, the quality of our outcomes is driven by the quality of how we practice. Second, change without measurement is not change. Third, we must rid ourselves of our mindset of orthodontic exceptionalism and restore humility within ourselves and our practices. Fourth, we must take the initiative to measure our personal performance and practice performance on the basis of our deeds, patient feedback, and professionalism — profit or production should be secondary determinants of success.

Never accept the proposition that just because a solution satisfies a problem, that it must be the only solution.

— Raymond E. Feist

More specifically, we should implement broader system wide measures at multiple levels to understand and improve upon the quality of care we offer patients. At the patient level, measures should include whether patient care expectations are met, the number of disruptive episodes in the patient’s life (e.g., wait times, discomfort), and the patient’s understanding of his/her care needs and treatment. Such measures would provide a gauge for the effectiveness of the patient’s care experience in the practice.

At the doctor level, measures should include the proximity of the initial plan to the outcome and the conformity of her treatment approach to the prevailing evidence. Such measures would provide a basis for assessing the doctor’s knowledge and skills and also shed light on the effectiveness of the quality assurance program in the practice. I also believe that the doctor should periodically make available his/her report card to the public. The societal benefit of such transparency outweighs the limited loss of professional freedom.

At the process level, measures should include error rates, acts of commission and omission, resource utilization, and cost-effectiveness of care. Learnings from these measures would provide an understanding of the effectiveness of the practice’s quality- control program. Furthermore, quality should be measured temporally. The trend line would reveal the effectiveness of continual improvement initiatives in the practice. Generative practices would tend to show a positive trajectory in their efforts to continually improve.

Always do right — this will gratify some and astonish the rest. — Mark Twain

At the system-wide level, the profession must implement a total quality assessment program and patient literacy program to educate the patient on the metrics of quality care. Furthermore, we must establish a national registry to report the errors or adverse events we see during our patient care. It is only by sharing and collectively learning from our failures that our specialty can better patient care.

Academia should implement educational and effective training programs on patient safety and improvement science for the residents and the practicing community. They should also take the responsibility to regularly report on their institutional care performance to both the public and professional communities.

Industry must take an active and responsible role in working with the professional community to educate the public on quality care.

Our calling as orthodontists is to carry the slogan “always do right by the patient.” Let this be the mantra that raises our professional conscience to the highest of levels. Let it also be a reminder to us to serve our patients to the best of our abilities. A positive externality of quality patient care is the sustainability of the orthodontic profession.

This manifesto forms the bedrock of BioDigital orthodontics, a philosophy of care that I have developed. In my next article, I will discuss the principles and practice of Bio-Digital orthodontics with specific reference to building reliable care practices through error minimization.

Acknowledgments

This article is republished with permission from the European Journal of Clinical Orthodontics — Sachdeva RCL. Novus Ordo Seclorum. A manifesto for practicing quality care — part 1. EJCO. 2014;2:71-76. I sincerely thank the publishers and editors of the European Journal of Clinical Orthodontics, Dr. Raffaele Schiavoni and Ms. Lorella La Leggia for giving me permission to publish the above article in Orthodontic Practice US. Also, I wish to express my sincerest gratitude to my daughter, Nikita Sachdeva, for her editorial assistance.

- American Board of Orthodontics (ABO). Grading System for Dental Casts and Panoramic Radiographs. ABO. June 2012. https://www.americanboardortho.com/media/1191/grading-system-casts-radiographs.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- NHS West Norfolk Clinical Commissioning Group. Quality and Patient Safety. National Health Service West Norfolk Clinical Commissioning Group. 2014. https://www.westnorfolkccg.nhs.uk/about-us/quality-patient-safety. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- Hartzband P, Groopman J. The new language of medicine. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1372-1373.

- Dorr Goold S, Lipkin M Jr. The doctor-patient relationship: challenges, opportunities, and strategies. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(Suppl 1):S26-S33.

- Berwick DM. What “patient-centered” should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4):w555-w565.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on a Patient’s Bill of Rights and Responsibilities. 2009;37(6):188-119. https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_patientbillofrights.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- Tonelli MR. Advancing a casuistic model of clinical decision making: a response to commentators. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(4): 504-507.

- Sachdeva RCL. Integrating Digital and Robotic Technologies: Three-Dimensional Modeling, Diagnosis, Treatment Planning, and Therapeutics. In Graber L, Vanarsdall R, Vig K, eds. Orthodontics: Current Principles and Techniques. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, Inc.; 2012.

- Emanuel L, Berwick D, Conway J, Combes J, Hatlie M, Leape L, Reason J, Schyve P, Vincent C, Walton M. What Exactly Is Patient Safety? In Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML. eds. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008.

- Resar RK. Making Noncatastrophic health care processes reliable: learning to walk before running in creating high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res. 2006; 41(4 Pt 2):1677-1689.

- Roberts KH. and Bea RG. “Must accidents happen? Lessons from high-reliability organizations.” Academy of Management Executive, 2001;15(3):70-79.

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM. Managing the unexpected: resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. San Francisco, California:Jossey-Bass;2007.

- Fogel J, Janani R. Intentions and Behaviors to Obtain Invisalign. Journal of Medical Marketing. 2010;10(2):135-145.

- Invisalign. Invisalign Teen Mom Advisory Board Disclosure Statement. Invisalign. 2014. Web. 23 Aug. 2014. https://www.invisalign.com/pages/mabdisclosure#sm.0001pfsd3awaieofv7c1yk4obr8tm. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- NHS Lanarkshire. “Clinical Effectiveness Strategy: 2009-2012.” NHS Lanarkshire. June 2009;1-13. https://www.nhslanarkshire.org.uk/boards/Archive/2009BoardPapers/Documents/June%202009/Clinical%20Effectiveness%20Strategy%202009-2012%20-%20June%202009%20Board.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- Sollecito, W, Johnson J. McLaughlin and Kaluzny’s Continuous Quality Improvement in Health Care. 4th ed. Burlington Massachusetts:Jones & Bartlett Learning:2011.

- National Health Service (NHS). Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS). NHS. Updated January 21, 2015. https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/thenhs/records/proms/Pages/aboutproms.aspx. Accessed August 3, 2016.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Abstract

Abstract Rohit C.L. Sachdeva, BDS, M Dent Sc, is a consultant/coach with Rohit Sachdeva Orthodontic Coaching and Consulting, which helps doctors increase their clinical performance and assess technology for clinical use. He also works with the dental industry in product design and development. He is the co-founder of the Institute of Orthodontic Care Improvement. Dr. Sachdeva is the co-founder and former Chief Clinical Officer at OraMetrix, Inc. He received his dental degree from the University of Nairobi, Kenya, in 1978. He earned his Certificate in Orthodontics and Masters in Dental Science at the University of Connecticut in 1983. Dr. Sachdeva is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics and is an active member of the American Association of Orthodontics. In the past, he has held faculty positions at the University of Connecticut, Manitoba, and the Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M. Dr. Sachdeva has over 90 patents, is the recipient of the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science Award, and has over 160 papers and abstracts to his credit. Visit Dr. Sachdeva’s blog on

Rohit C.L. Sachdeva, BDS, M Dent Sc, is a consultant/coach with Rohit Sachdeva Orthodontic Coaching and Consulting, which helps doctors increase their clinical performance and assess technology for clinical use. He also works with the dental industry in product design and development. He is the co-founder of the Institute of Orthodontic Care Improvement. Dr. Sachdeva is the co-founder and former Chief Clinical Officer at OraMetrix, Inc. He received his dental degree from the University of Nairobi, Kenya, in 1978. He earned his Certificate in Orthodontics and Masters in Dental Science at the University of Connecticut in 1983. Dr. Sachdeva is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics and is an active member of the American Association of Orthodontics. In the past, he has held faculty positions at the University of Connecticut, Manitoba, and the Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M. Dr. Sachdeva has over 90 patents, is the recipient of the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science Award, and has over 160 papers and abstracts to his credit. Visit Dr. Sachdeva’s blog on