Dr. William (Bill) Harrell, Jr. says that airway and esthetics should both be addressed to meet the individual needs of children as they grow.

Dr. William E. Harrell, Jr. offers some insights into the history, growth, and importance of airway health

There is a controversy looming in dentistry as it relates to the role of orthodontics in airway health.

- Should orthodontics only be concerned with smile esthetics, facial balance, periodontal health, occlusion, and stability?

- Should orthodontics, including dentofacial orthopedics, be concerned with airway/breathing disorders?

Orthodontic treatment has focused on smile esthetics, facial esthetics, and dental occlusion since its inception,1 and “smile design” has become an important aspect of esthetic dentistry and orthodontics.2 The human airway, especially as it relates to mouth breathing versus nasal breathing affecting health and craniofacial growth, has been an important topic in orthodontics for well over 100 years.3 Unfortunately, with the passage of time, this knowledge has been overlooked, misunderstood, criticized, and forgotten.

This article presents the connection of airway, breathing, smile esthetics, occlusion, and TMJ disorders and how these should be considered as integral parts of the education, training, and integration of a new orthodontic paradigm, as research in medicine and dentistry are confirming that early screening for breathing disorders at age of 3 years old and improving craniofacial growth early (before 6), improves not only dental and facial esthetics, periodontal health, and occlusion, but more importantly, overall breathing and airway dynamics for improvement of long-term health.4 Furthermore, Welkoborsky, et al. (2022),5 found that reproducible rhinomanometric measurements were possible in children aged 3 years and older prompting endorsements from academia healthcare system and providers known as “We Can See at 3.” This new finding prompts screening and rhinomanometry testing with patient cooperation as soon as 3. Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in children and its long-term negative effects were first described by the late Christian Guilleminault, MD (CG), one of the “fathers of sleep medicine” at Stanford University in 1976.6,7 Early intervention and growth guidance were advocated by CG, and researchers presently at Stanford University6-10 and other experts at other prestigious universities and clinics around the world.6,11-13 This is now known as “Fix Before 6” by the Children’s Airway First Foundation (www.childrensairwayfirst.org) which was founded by Brad and Candy Sparks.

As stated by CG,6,12,14 establishing proper nasal breathing is critical for improving health and decreasing the effects or possibly even eliminating potential co-morbidities later in life. These problems have been associated with obstructive breathing disorders, both during the day and asleep. Additional benefits include creating esthetic and functional results as part of the complete orthodontic and dentofacial orthopedic treatment of our patients. Orthodontics/Dentistry/Dentofacial Orthopedics, which includes airway health, will bring medicine and dentistry closer together. An interdisciplinary team with other allied healthcare professionals and a coordinated approach with a common goal of airway and breathing health is the key to successful treatment of our mutual patients. Diverse opinions are shared and filtered with objective clinical and academic research, leading to diagnosis which then evolves into evidence-based and experience-based therapies. The success or failures of these therapies will vary from patient to patient and doctor to doctor for many reasons. These experiences circle back to confirm or refine the diagnosis and add to clinical knowledge when shared. Patients win when professionals, who may not totally agree with each other, openly share true experiences. Remember, at one time surgeons never washed their hands, put on gloves, or used masks.

Arthur Perry Gordy, DDS, an orthodontist from Columbus, Georgia, is quoted in his article of 1929:15 “In 1836, Charles Dickens, [in the “The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club”16], pointed out the relationship between open mouth, backwardness, and delinquency, that would have saved millions of lives and would have averted millions of life failures had the civilized world realized the true importance of his [Dickens] words.” Dr. C.E. Kells of New Orleans (the father of dental radiography) sent this quote as part of his letter congratulating Dr. Gordy: “You have given the profession and the world something worthwhile; don’t be discouraged — remember Jenner, Pasteur, Roentgen, and Wells.”15,17

Increased nasal resistance, from allergies, habits, or genetics, during growth years affects the craniofacial growth pattern by the alteration of functional nasal airflow and an increased effort to nasal breathe.6,12 This increased effort and strain on the system affects the development of the heart, brain, and other organ systems of the body.18,19 Intraluminal pressure changes from respiratory effort cause structural effects such as narrowed naso-maxillary complex, enlarged turbinates, deviated septum, and altered posture of the mandible, tongue, and head. A conversion to mouth breathing leads to changes in brain function,19 cardiovascular effects, a long facial growth pattern with an obtuse mandibular plane angle and TMJ degenerative changes, resulting in more clockwise rotation of the mandible and encroachment on the airway. This backward growth, along with a lower tongue posture and hyoid position, may lead to a more collapsed airway in the pharyngeal area and naso-maxillary complex in all three planes of space. This results in further increase in nasal resistance.20,21

Health professionals are concerned with long-term implications of this poor growth pattern. CG said, “Pediatric OSA in non-obese children is a disorder of oral-facial growth.”6 Because of the many signs, symptoms, and etiologies involved, evaluation and therapy by Allergist/Sleep Physician/Pediatrician/Dentist/Speech Pathologist/Myofunctional Therapists/ENT is critical for success. What is necessary is expertise in the growth of the craniofacial respiratory complex, more common in pediatric and orthodontic residencies than in many other parts of medical and dental training. Any or all of these disciplines may be required to meet the needs of the individual child at risk.

Imaging

Static 2D imaging such as lateral cephalometric x-rays and advanced 3D volumes, like CBCT, are being used to evaluate the airway. No static imaging can provide dynamic functional information of airway resistance or air flow especially in the nasal region. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), a computer modelling of airflow, and functional MRI (fMRI) of nasal versus mouth breathing are promising new technologies that might be helpful but are just beginning to be researched. Changes to the pharyngeal airway between upright, supine, awake, and sleep states cannot be predicted by static imaging due to variable responses of airway dilator muscle activity and mucosal tissues.

When considering pressure changes and their effects on growth, principles of physics aid in the understanding of how an increase in nasal resistance creates an upstream problem for the craniofacial respiratory complex with a down-stream effect. A deviated septum (Figures 1A and 1B) can cause a 38%-55% increase in nasal resistance versus the open side and results in a pressure drop of 60%-120%.22 In a growing child, this distorts the shape of airway structures, but is often not discovered until much later in life. Notice the deviated septum (blue arrow) to the left and swollen right middle turbinate (red arrow) and swollen left inferior turbinate (yellow arrow). This is the same patient shown in Figures 3A-4C using 4-Phase Rhinomanometry and Acoustic Rhinometry.

The objective nasal resistance measurements correlate to the structural alterations. Also note the skeletal constriction of the naso-maxillary complex and the dentoalveolar maxillary constriction shown by the lingual inclinations of the maxillary first molars and the narrow maxillary intermolar width (orange arrow 28.2 mm, normal ranges from 36-49 mm4,12,23) contributing to the low tongue posture.

Esthetics

Smile esthetics has always been the mainstay of traditional orthodontic therapy. The esthetic quality of the smile is improved with a wider smile, improved buccal corridors, and a consonant smile arc, etc. Expansion of the maxillae and uprighting the teeth over basal bone while optimizing their AP location accomplishes these goals. Matching mandibular arch dimensions within the more limited boundary conditions available also improves tongue space and airway dimension in the naso-maxillary-mandibular complex (Figures 2A-2C). Figures 2D and 2E show after skeletal expansion either with surgery or skeletal/dentoalveolar enlargement using some form of palatal transverse expansion and/or uprighting and AP development when needed. This results in not only good smile and facial esthetics with broad arches and no dark buccal corridors, but also positively affecting airway dimensions with decreased resistance and increased airflow.

An article by Eric Thuler, MD, PhD (Division of Sleep Surgery, Dept of Otorhinolaryngology, University of Pennsylvania — Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), entitled “Transverse Maxillary Deficiency Predicts Upper Airway Collapsibility during Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy”24,25 stated, “Our results further the concept that skeletal restriction in the transverse dimension and hyoid descent are associated with elevations in pharyngeal collapsibility during sleep, suggesting a role of transverse deficiency in the pathogenesis of airway obstruction.”

Measuring nasal resistance

Dynamic airflow through the nose should be objectively measured to aid evidence-based diagnosis and to monitor therapy. The technology is based on the pressure/flow relationship in the awake state in both sitting and supine positions. As a gold standard of care, each level of pressure change dictates the treatment option through interpretation as well as the monitoring of progress pre, mid, and post treatment. The concept of the technology was founded on the physics of “manometry,” the study of pressure measurements and function such as measuring air flow through transnasal pressure differences (Figures 3A-3C). This data is obtained with 4-Phase Rhinomanometry, a technology invented and developed by Dr. Klaus Vogt, MD, DDS, PhD, an ENT, dentist, and PhD since 1966.26

In 1983, The International Standardization Committee on the Objective Assessment of the Nasal Airway (ISCOANA) consisting of experts from Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, Latvia, and Ukraine, representing physics, mathematics, statistics, fluid dynamics, biotechnology, and clinical rhinology was formed to write a consensus on the validity of objective measurements of the nasal airway. The committee, chaired and created by Dr. Vogt, last met in Riga, Latvia on the November 2, 2016 to address the existing nasal airway function tests and to take into account physical, mathematical, and technical correctness as a base of international standardization as well as the requirements of the Council Directive 93/42/EEC of 14 June 1993 concerning medical devices. This was necessary because some of the diagnostic procedures currently in use in rhinology, and now dentistry, no longer fulfil the requirements of quality management for medical devices. In addition, recent studies critically evaluating techniques for nasal airway assessment have not addressed technical progress in this field in recent years and the resulting experimental work, which has a great impact on daily practice.

Figure 3A shows the 4 Phase Rhinomanometer unit. Figure 3B shows the Nasal Resistance graph of the right side. The “Tall Lazy S” represents a normal result. The Mean Resistance of the Right Inspiration is 0.262 and Right Expiration is 0.315, which are close to the normal range less than 0.33 Pa/cm3/sec. Normative values differ based on age, gender, race, and other factors. Women have higher levels of nasal resistance than men, and children even higher, especially neonates. By age five, resistance decreases by 50%. There is continual reduction due to growth of the airway bounding structures until adult resistance is reached. Disease can disrupt this progression at any stage.

Figure 3C the left side, shows the graph as almost a flat line which shows severely limited nasal flow. Mean Resistance on Inspiration of 3.995 Pa/cm3/sec and on expiration of 12.391 Pa/cm3/sec. See CBCT in Figures 1A-1B.

To enhance communication of outcomes, an algorithm has been developed by Karen Davidson, RN, PhD,27 called the DAFNE SCORE (www.DAFNESCORE.com), to help clarify the results and give suggestions of common therapies and interprofessional collaboration. The clinician enters data from rhinomanometry; the software provides medically sound guidance.

It is important to understand the differences between rhinomanometry, a measurement of airflow and rhinometry, a structural assessment.

Rhinomanometry measures transnasal pressure differences in the nose — Resistance, Function, Flow (Figures 3A-3C).

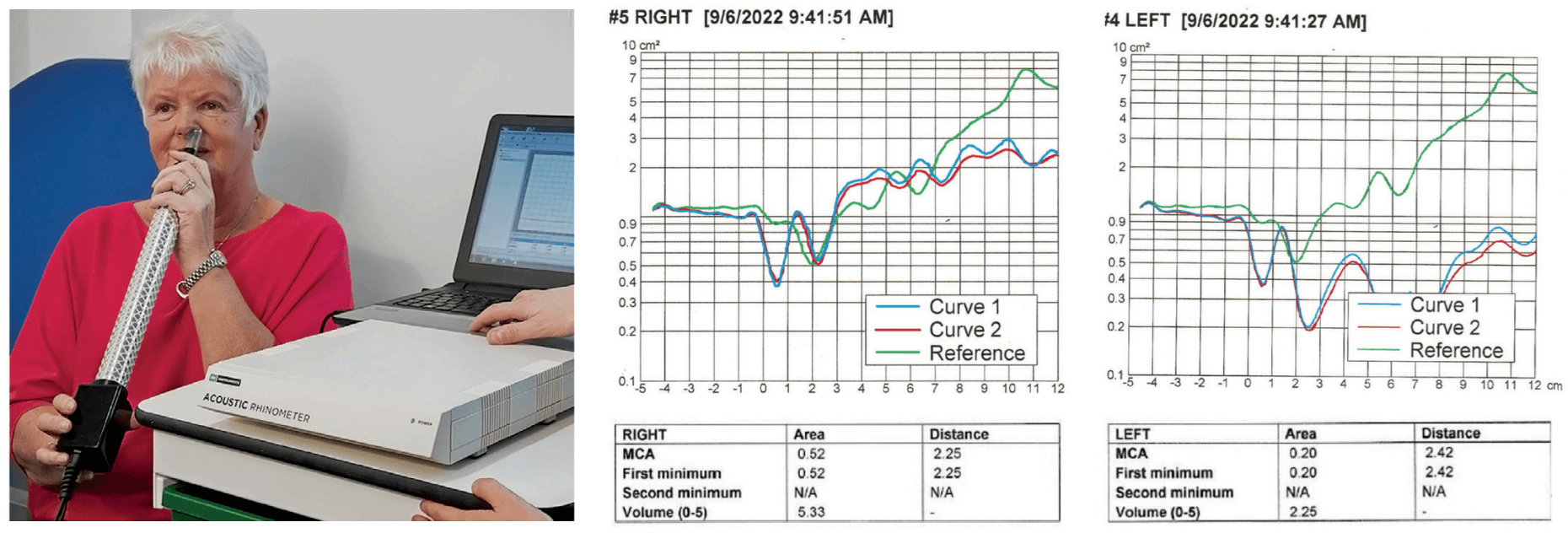

Acoustic Rhinometry measures structure/geometry of the nasal cavity using sound waves like sonar (Figures 4A-4C).

Figure 4A shows the acoustic rhinometer being used. The tube sends sound waves (like sonar) through the nose to determine structural integrity.

In Figure 4B, the nasal structure graphs are more closely aligned with the normal curve (green curved line).

In Figure 4C, the measurements of nasal structure in the nasal cavity show that the bottom graphs (red/blue curved lines) are well below the top graph (green curved line) which represents the normal of nasal structure from the nares to the naso-pharynx. These graphs (red/blue curved lines) below the normal curve — (green curved line) represent significant structural abnormality which can be from hard tissues and/or soft tissue being responsible for the obstruction.

When decongested and repeated, if the acoustic waves become closer to the “normal curve” that suggests a soft tissue issue. If there is little to no change, that represents a hard tissue problem. This is extremely important for proper diagnosis of soft tissue issues versus hard tissue issues leading to proper therapy from a MD, ENT, orthodontist, dentist, etc.

A new comprehensive textbook to be published by Springer in mid-to-late 2024 entitled Growing into Breathing Problems: The Quest for Collaborative Lifetime Solutions,11 will discuss pediatric and adult screening and diagnosis, medical and dental therapies, early versus late treatment options, myofunctional therapy, objective measurements of nasal resistance, and surgical solutions. The editors are: William E. Harrell, Jr, DMD, ABO, C.DSM; Pediatric Pulmonologist David Gozal, MD, MBA, PhD; and Pediatric ENT David McIntosh, MBBS, FRACS, PhD, plus 25 other experts in their respective fields.

Mini, micro, and macro smile esthetics, smile projection, smile arc, consonant smile, buccal corridors, etc. are all considered esthetic qualities of a successful and esthetic orthodontic outcome.2 These qualities should be expanded (no pun intended) to the area of improving craniofacial growth, airway, breathing, and TMJ function. Our forefathers in orthodontics were very aware of how obstructed breathing alters craniofacial growth and its effect on the physiology of the body, the occlusion, and dental/facial esthetics.3 Sometimes, we must go back into history — in order to proceed to the future.

Airway and esthetics can be affected by lip closure. Read more about issues that can be caused by ineffective lip closure in “Shut your mouth and save your life: the problem with interlabial gap,” by Dr. Michael Gunson here: https://orthopracticeus.com/ce-articles/shut-your-mouth-and-save-your-life-the-problem-with-interlabial-gap1/. Subscribers can receive 2 CE credits after passing the quiz!

- Asbell MB. A brief history of orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990 Sep;98(3):206-213.

- Sarver D. Smile projection-a new concept in smile design. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021 Jan;33(1):237-252.

- Kim KB. How has our interest in the airway changed over 100 years? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015 Nov;148(5):740-747.

- Thuler E, Rabelo FAW, Yui M, Tominaga Q, Dos Santos V Jr, Arap SS. Correlation between the transverse dimension of the maxilla, upper airway obstructive site, and OSA severity. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Jul 1;17(7):1465-1473

- Welkoborsky HJ, Rose-Diekmann C, Vor der Holte AP, Ott H. Clinical parameters influencing the results of anterior rhinomanometry in children. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 Aug;279(8):3963-3972.

- Huang YS, Guilleminault C. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea and the critical role of oral-facial growth: evidences. Front Neurol. 2013 Jan 22;3:184.

- Guilleminault C, Eldridge FL, Simmons FB, Dement WC. Sleep apnea in eight children. Pediatrics. 1976 Jul;58(1):23-30.

- Yoon A, Abdelwahab M, Bockow R, Vakili A, Lovell K, Chang I, Ganguly R, Liu SY, Kushida C, Hong C. Impact of rapid palatal expansion on the size of adenoids and tonsils in children. Sleep Med. 2022 Apr;92:96-102.

- Guilleminault C, Sullivan SS. Towards restoration of continuous nasal breathing as the ultimate goal in pediatric OSA. Enliven: Pediatr Neonatol Biol. 2014;1(1).

- Iwasaki T, Yoon A, Guilleminault C, Yamasaki Y, Liu SY. How does distraction osteogenesis maxillary expansion (DOME) reduce severity of obstructive sleep apnea? Sleep Breath. 2020 Mar;24(1):287-296.

- Harrell W, Gozal D, McIntosh D. Growing into breathing problems: the quest for collaborative lifetime solutions. Springer Publishing in Press 2024.

- McNamara JA. Maxillary transverse deficiency. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000 May;117(5):567-570.

- Krishnaswamy NR. Expansion in the absence of crossbite – rationale and protocol. APOS Trends Orthod 2019;9(3):126-137.

- Marin-Oto M, Vicente EE, Marin JM. Long term management of obstructive sleep apnea and its comorbidities. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2019 Jul 4;14:21.

- Gordy AP. Mouth breathing and a few facts seldom discussed. The cause, effect & treatment of malocclusion with specific reference to pernicious habits as affecting the physiognomy. Published and presented before the GA State Dental society, 1929.

- Dickens C. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Chapman & Hall Publishers; 1836.

- Gordy AP. Nose and throat conditions and allied habits in relation to irregularities of the teeth and development of the jaws. National Health Assoc, 4th District Dental Society of GA; 1929.

- Zelano C, Jiang H, Zhou G, Arora N, Schuele S, Rosenow J, Gottfried JA. Nasal Respiration Entrains Human Limbic Oscillations and Modulates Cognitive Function. J Neurosci. 2016 Dec 7;36(49):12448-12467.

- Jung JY, Kang CK. Investigation on the Effect of Oral Breathing on Cognitive Activity Using Functional Brain Imaging. Healthcare (Basel). 2021 May 29;9(6):645.

- Harvold EP, Tomer BS, Vargervik K, Chierici G. Primate experiments on oral respiration. Am J Orthod. 1981 Apr;79(4):359-372.

- Linder-Aronson S, Backstrom A. A comparison between mouth and nose breathers with respect to occlusion and facial dimensions. Odont Rev. 1960;2:343-376.

- Corda JV, Shenoy BS, Lewis L, Prakashini K, Khader SMA, Ahmad KA, Zuber M. Nasal airflow patterns in a patient with septal deviation and comparison with a healthy nasal cavity using computational fluid dynamics. Front. Mech. Eng., Sec. Biomechanical Engineering. 2022;8.

- Azlan A, Mardiati E, Evangelina IA, A gender-based comparison of intermolar width conducted at Padjajaran University Dental Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia. Dental Journal: Majalah Kedokteran Gigi. 2019;52(4):168-171.

- Thuler E, Seay EG, Woo J, Lee J, Jafari N, Keenan BT, Dedhia RC, Schwartz AR. Transverse Maxillary Deficiency Predicts Increased Upper Airway Collapsibility during Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 Aug;169(2):412-421.

- Hutz MJ, Thuler E, Cheong C, Phung C, Evans M, Woo J, Keenan BT, Dedhia RC. The Association Between Transverse Maxillary Deficiency and Septal Deviation in Adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Laryngoscope. 2024 May;134(5):2464-2470.

- Vogt K, Jalowayski AA, Althaus W, Cao C, Han D, Hasse W, Hoffrichter H, Mösges R, Pallanch J, Shah-Hosseini K, Peksis K, Wernecke KD, Zhang L, Zaporoshenko P. 4-Phase-Rhinomanometry (4PR)–basics and practice 2010. Rhinol Suppl. 2010;21: 1-50.

- Davidson K, Harrell W. Validation of a Novel User Interface and Calculation Method for Determining Nasal Resistance and Patency, in press 2024.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

William (Bill) Harrell, Jr., DMD, ABO, C.DSM, graduated from the University of Alabama School of Dentistry in Birmingham in 1975 and completed his orthodontic residency at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in 1977. He is a Board-Certified Orthodontist (ABO) in private practice in Alexander City, Alabama and Auburn/Opelika, Alabama. Dr. Harrell is also Certified in Dental Sleep Medicine. Dr. Harrell has served as VP and President of the Alabama Association of Orthodontists as the Secretary-Treasurer, VP, and President of the 9th District Dental Society of Alabama; and served on The Board of Trustees and in the House of Delegates of the Alabama Dental Association. He has also served on various committees of the American Association of Orthodontists. Dr. Harrell is the first orthodontic private practice in Alabama to have ConeBeam CT (CBCT) and the first in the US to combine both CBCT and 3D facial imaging (3dMD) in early 2005. Dr. Harrell’s practice focuses on airway-centered orthodontic diagnosis and treatment and TMJ Disorders. Dr. Harrell is the Chairperson of the RadSite ConeBeam CT Standards Committee for setting standards for the insurance industry of reimbursement.

William (Bill) Harrell, Jr., DMD, ABO, C.DSM, graduated from the University of Alabama School of Dentistry in Birmingham in 1975 and completed his orthodontic residency at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in 1977. He is a Board-Certified Orthodontist (ABO) in private practice in Alexander City, Alabama and Auburn/Opelika, Alabama. Dr. Harrell is also Certified in Dental Sleep Medicine. Dr. Harrell has served as VP and President of the Alabama Association of Orthodontists as the Secretary-Treasurer, VP, and President of the 9th District Dental Society of Alabama; and served on The Board of Trustees and in the House of Delegates of the Alabama Dental Association. He has also served on various committees of the American Association of Orthodontists. Dr. Harrell is the first orthodontic private practice in Alabama to have ConeBeam CT (CBCT) and the first in the US to combine both CBCT and 3D facial imaging (3dMD) in early 2005. Dr. Harrell’s practice focuses on airway-centered orthodontic diagnosis and treatment and TMJ Disorders. Dr. Harrell is the Chairperson of the RadSite ConeBeam CT Standards Committee for setting standards for the insurance industry of reimbursement.