Drs. Bethany R. Middleton, Donald J. Rinchuse, and Thomas G. Zullo investigate current trends of treatment alternatives for white spot lesions

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to investigate the efficacy of MI Paste™ compared to fluoride used in mitigating white spot lesions. Simultaneously, a survey was designed to investigate current trends of treatment alternatives for white spot lesions utilized by private orthodontic practitioners.

[userloggedin]

Methods: A pilot study was conducted in a split-mouth trial comparing MI Paste versus fluoride gel. Subjects had baseline photographic records taken and were randomly assigned treatment options by arch, with each arch subdivided into quadrants of treatment and control. After 6 weeks of treatment, subjects were presented with a direct comparison of before-and-after photographs. Questionnaires were developed to evaluate each subject’s perception of change prior to and after seeing their photographs. A blinded panel of dental experts evaluated the appearances of the white spots before and after treatment using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS). In conjunction with this study, an email requesting participation in a seven-question online survey (Survey Monkey®) was sent to active and retired members of the AAO from the AAO Partners in Education, (n = 2300).

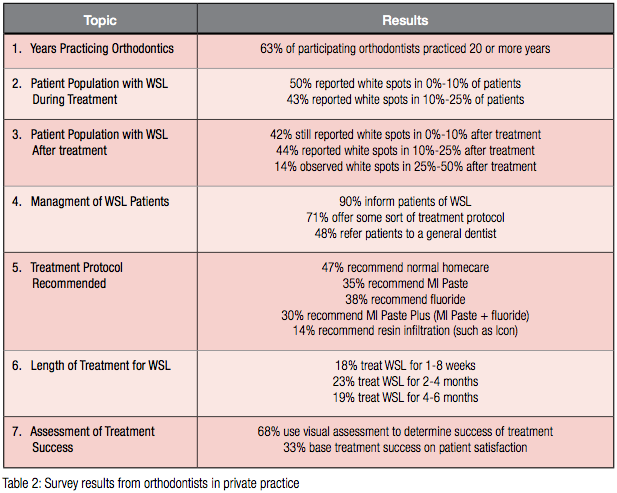

Results: Subjects were generally pleased with changes in the appearance of their teeth. No statistically significant differences were discovered between MI Paste, fluoride gel, and the control. Although most quadrants reflected improvement, some did not. In the survey, 93% of practitioners observed white spot lesions in up to 25% of patients during treatment, which increased to 25%-50% after orthodontic treatment. 90% of orthodontists will at least inform patients of white spots. 71% offer a treatment protocol: 47% recommend normal home care, 35% recommend MI Paste, 38% recommend fluoride, and 30% will recommend MI Paste Plus™, a combination of fluoride and RecaldentTM. Nearly half of private practitioners will refer patients to a general dentist for treatment of white spot lesions.

Conclusions: A number of products claim to reverse the appearance of white spot lesions; however, this pilot study demonstrated that, despite minor improvements, evidence is lacking whether any product, including normal home care, is superior. Subjects unanimously reported satisfaction with white spot treatments, despite varying outcomes. Orthodontists observing white spot lesions will recommend a variety of treatment alternatives for patients, which is reflective of the variety of recommendations seen in the literature.

Introduction

White spot lesions can be described as porosities below the smooth surfaces of enamel that appear milky white due to altered light scatter.1-2 They have been a recurrent problem in orthodontic patients for decades, with little prevention being demonstrated in the recent past. These white spots have been reported to range in occurrence from 2%–96%3-6 of treated patients, presenting themselves as one of the most challenging drawbacks to orthodontics. As demonstrated by a survey, patients, parents, dentists, and orthodontists agree that such lesions not only diminish appearances of teeth, but also are ultimately the responsibility of the patient when it comes to prevention.7 Identifying potential patients to target such prevention is a challenge in and of itself. However, determining what to do after these lesions have formed is an even greater dilemma. A number of studies recommend preventative treatments ranging from fluoride products (pastes, gels, varnishes, mouth rinses, etc.) to antimicrobials, xylitol gum, diet counseling, and casein derivatives.8-28

Two of the most popular treatment products currently being compared for effectiveness are fluoride products and the casein derivative known as casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP). In a recent study, fluoride varnish demonstrated itself to have slightly greater improvements than that of a CPP-ACP product known as MI Paste when subjects evaluated before and after photographs of treatments with said products.29 Often, fluoride is recommended more as a preventive measure in the inhibition of demineralization.9-12 CPP-ACP functions as a calcium and phosphate-binding agent which can adhere to both bacterial walls and the surfaces of teeth.24, 25 In acidic environments, these ions can be released to form a supersaturated ion concentration in the saliva, which releases the calcium-phosphate compound as a precipitate on the tooth surface.25 Recaldent™ (CPP-ACP) has made claims of remineralizing and reversing white spot lesions, decreasing tooth sensitivity, aiding in salivary flow for dry mouths, etc.

White spot lesions developing during orthodontic treatment can be described as active or arrested, with active lesions having a better prognosis for recovery; this is due to the porosity of the enamel, which allows for uptake of the calcium-phosphate ions.8 Generally, patients who have completed orthodontic treatment have progressed to an arrested state, indicating a remineralization of the outer enamel layer, making the process for reversal or esthetic matching much more difficult.8 One study showed that subjects who were in active orthodontic treatment and used MI Paste Plus™ (MI Paste with 900 ppm sodium fluoride concentration) during treatment demonstrated improvement of existing white spot lesions and prevention of others, while the control subjects had increased incidence of WSLs and worsening of existing lesions.30 However, in another recent study, home care was found to be nearly as effective as either MI Paste Plus™ or PreviDent® 5000 (Colgate®) fluoride varnish.29 While this was performed within 2 months post-orthodontics, and for 8 weeks at home, it can be surmised that some remineralization may occur naturally. Several publications have recommended allowing this to occur for up to 6 months, and then applying bleaching for esthetic matching, or low concentrations of fluoride, or MI Paste’s Recaldent™.8,29,31 Other studies attributed a greater occurrence in WSLs to the type of bonding materials used on brackets, with glass ionomer cement showing less harm than acrylic bonding materials long-term.32,33

Materials and methods

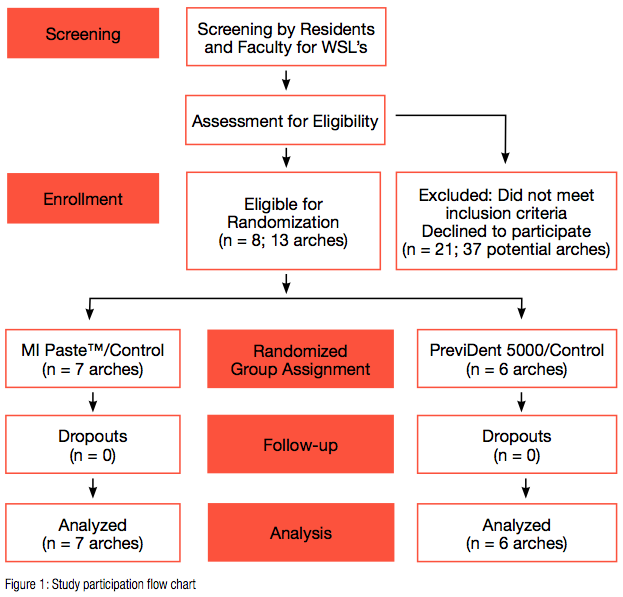

This study was designed with two parts: a pilot study for a clinical trial to evaluate post-orthodontic white spot treatments, as well as a survey to discover current trends of orthodontists in private practice. The study design was somewhat modeled after previous studies by Robertson, et al., at the Department of Orthodontics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; University of Alabama at Birmingham; and Ann Arbor, Michigan30; and also Huang, et al.,29 at Seattle and Bellevue, Washington, and Boise, Idaho. A flow chart was created for this trial (Figure 1).

This study was designed with two parts: a pilot study for a clinical trial to evaluate post-orthodontic white spot treatments, as well as a survey to discover current trends of orthodontists in private practice. The study design was somewhat modeled after previous studies by Robertson, et al., at the Department of Orthodontics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; University of Alabama at Birmingham; and Ann Arbor, Michigan30; and also Huang, et al.,29 at Seattle and Bellevue, Washington, and Boise, Idaho. A flow chart was created for this trial (Figure 1).

This research protocol was approved by the Seton Hill University Institutional Review Board. After conducting a power analysis for the trial, it was deemed too difficult to obtain a sample size large enough to create a statistically significant result from the patient pool currently available at the Center for Orthodontics. Instead, the trial design was modified to a pilot study which could potentially be expounded upon in future trials. Eight participants (with a total of 13 qualifying arches, or 26 quadrants) met the inclusion criteria and were willing to commit to 6 consecutive weeks of treatment, signed minor assent agreements, with guardians signing informed consent agreements. The participants had affected arches randomly assigned into one of two groups in an attempt to closely approximate the groups based on age and gender. Both groups were further divided into split-mouth experiment and control quadrants. These subjects were recruited over time, as qualifications were met, then scheduled to begin and end the experiment over the same 6-week period. Treatment was conducted from September 23, 2013, to November 7, 2013. Group A had MI Paste (GC America, Alsip, Illinois) for the experimental substance, while Group B was given Colgate® PreviDent® 5000 gel (Colgate-Palmolive, New York, New York). The control product was Tom’s of Maine non-fluoridated whitening toothpaste (Kennebunk, Maine). Subject randomization has a number of advantages, including selection bias reduction ensuring that certain study participants are not funneled into one group or another based on factors that could influence trial results. It allows for the incorporation of the probability theory to determine the likelihood that outcome differences are due to chance alone, and also serves as a means of investigator and subject blinding.

In an attempt to account for and reduce selection bias, the principal investigator was not involved in the process of subject allocation to the two groups. After initial identification of subjects who fit the inclusion criteria, a staff member from Seton Hill University Center for Orthodontics randomly assigned the subjects using the flip of a coin. At the initial treatment appointment, a baseline level of the location of white spot lesions qualifying for the study was assessed and charted. Initial intraoral photographic records were taken. This was repeated after 6 weeks of treatment to evaluate progression or reversal of white spot lesions in both the Recaldent™ and fluoride groups.34-39 Three standard photographs were taken from the left buccal, right buccal, and centered anterior aspects to evaluate from first molar to first molar in both the maxilla and mandible. A single camera (Canon EOS 1000D Rebel XS) was used to take photos in a light-controlled environment to ensure consistency.

Each subject was instructed to brush prior to the beginning of each treatment session. All qualifying tooth surfaces were pumice polished and rinsed. Lip retractors were then placed to reduce saliva contamination and allow adequate access to involved surfaces. These surfaces were etched with 37% phosphoric acid gel for 15 seconds, thoroughly rinsed, and dried. Each arch was then treated for with either MI Paste or PreviDent 5000 gel on one-half and a control of Tom’s of Maine on the other. Products were topically administered with a cotton-tipped applicator and left on for 4 minutes. The subjects expectorated and were instructed not to eat, drink, or rinse for 30 minutes. This protocol was conducted once a week for 6 weeks. Photographs were taken a week after the final treatment to prevent inaccurate appearances of desiccated teeth the day of the final treatment.

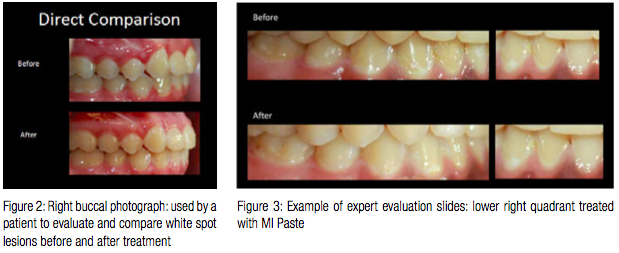

After treatment two questionnaires were created to assess the perception of treatment outcomes and any changes in behavior due to the study, such as a Hawthorne effect.40 The questionnaires were presented to a group of residents not participating in the study to assess clarity of questions and modify wording in lay terms. Final versions of the questionnaires were adopted and disseminated to the subjects and guardians prior to viewing before/after comparison photographs. They were presented with a personalized slide show (PowerPoint, Microsoft) displaying two standardized orientation slides, which the principal investigator used to explain the evaluation process of white spots. These slides were taken from a previous study after permission was granted from the original author and the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics (AJO-DO) Rightslink.29 Once subjects were oriented with evaluation protocols, they were shown before and after photographs of their teeth (Figure 2), and assessed overall changes by demarcating a 100-mm visual analog scale and describing the degree and type of changes observed. All subjects were given the opportunity to continue treatment if desired at the end of the study.

A panel of four dental experts were recruited to visually assess the differences in initial and final photographs of treated and control quadrants for all subjects. These evaluators were third-year orthodontic residents at Seton Hill University (two male, two female). All experts were presented with the same two orientation slides as the subjects and given oral instructions on how to evaluate changes using a 100-mm visual analog scale with a score of 0 indicating no improvement or worsening of a lesion and 100 indicating complete improvement or disappearance of the white spots. They were then presented with a 26-slide PowerPoint presentation, which displayed isolated photographs of each quadrant of treatment with side-by-side comparisons of initial and final photographs (Figure 3). Every assessor was blinded to the treatments rendered to each quadrant, and photos were not in sequential order of subjects so as to prevent evaluator fatigue.

For the survey portion of the study, approval was granted from the Seton Hill University Institutional Review Board, and a list of questions was compiled and reviewed by the investigator and faculty supervisor, as well as residents who were not participating in the study. It was then submitted for approval and review by American Association of Orthodontists Partners in Research. An email invitation was sent to active and retired members of the AAO (n = 2300) from the American Association of Orthodontists Partners in Education requesting participation in a seven-question online survey (Survey Monkey). These practitioners were asked to answer questions regarding their experience and in-office protocols for white spot lesions cause by orthodontics. The introductory letter informed members that the aim of the survey was to determine current trends in management and treatment of white spot lesions for private practitioners. The online survey was posted from October 24, 2013, to November 26, 2013. The survey link and cover letter were emailed to AAO members on two separate occasions. The survey questionnaire consisted of single-response, multi-response, and open-ended questions that gave members the opportunity to explain their answers. These questions were designed to discover the demographics and protocols of private practitioners. Questions were as follows: How long have you been practicing orthodontics? In approximately what percentage of your patients do you observe white spot lesions during treatment, after treatment? How do you manage patients with white spot lesions? If you offer a treatment protocol, what do you recommend? If you treat white spot lesions in-office, how long do you treat patients for improvement? If you treat white spot lesions in-office, how do you assess treatment success?

Results

A total of 29 subjects were initially identified as possible candidates for the pilot study. Of those subjects, 12 met the inclusion criteria, and 8 of those 12 consented to participate in the study (3 males, 5 females). All 8 subjects completed the entire 6-week treatment process, resulting in a drop-out rate of 0%. The MI Paste group was composed of 7 quadrants on 6 subjects. The PreviDent 5000 group was composed of 6 quadrants on 5 subjects.

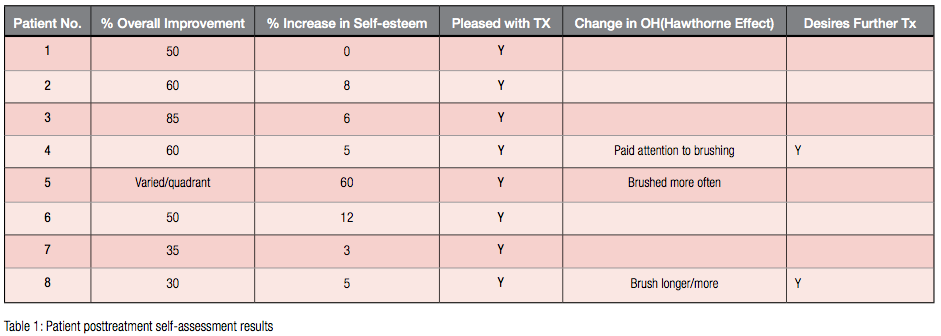

Data collected from the subject self-assessments were compiled into a table format, utilizing qualitative and quantitative measurements (Table 1). Quantifiable data were measured using a 100 mm VAS, measuring the differences between self-esteem regarding the appearances of their teeth before and after the white spot treatment. After viewing the side-by-side comparisons of the initial and final photographs, subjects noted a range in improvement of the white spots from 30%–85%. Increased self-esteem in regards to tooth appearance was less significant, ranging from 0%–12% with an outlier increasing by 60%. All subjects and guardians were pleased with the outcome of treatment regardless of the products used, and 75% of the subjects desired no further treatment after the 6-week study. Of the two subjects (25%) who elected to continue treatment, only one subject returned for an additional in-office treatment. Three subjects (37.5%) reported a change in behavior during the study, stating an increase in frequency and duration of brushing. One subject and her parent both separately noted a worsening in the appearance of a quadrant of treatment related to an increase in the white spot appearance. This quadrant was treated with PreviDent 5000.

Data were collected from the dental expert evaluators and all assessments were measured to the nearest millimeter, each millimeter correlating to a scale of 1% on the range from 0% (no improvement/worsening) to 100% (complete disappearance of the lesion). This information was then analyzed using SPSS v.19, incorporating transformed variables that were the mean of the four judges in an attempt to best correlate the relationships of the different treatment groups. A Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test revealed no significant difference between Group A and the Control (p = 0.686), or Group B and the Control (p = 0.345). Overall, mild improvements were noted, yet some quadrants showed no improvement at all.

For the survey, of the 2300 emails sent to active and retired AAO members, 1500 actually opened the emails, and 133 participated in the survey (Table 2). Of those who participated in the survey, 63% had been practicing for over 20 years. Of the practitioners surveyed, 93% observed a presence of white spot lesions in 25% or less of their patient population. After orthodontic treatment, 14% claimed that the prevalence rose to between 25%–50%. Just over 90% of orthodontists said they inform their patients of these white spots, and 71% offer a treatment protocol; 47% will recommend normal home care to aid in the reversal. Those who offer treatments of Recaldent TM, fluoride, or a combination were relatively evenly disseminated. 35% recommend MI Paste, 38% recommend fluoride, and 30% will recommend MI Paste Plus, which is a combination of fluoride and RecaldentTM. Nearly half (48%) of private practitioners will refer patients to a general dentist if needed.

Discussion

A number of prior studies have evaluated the efficacy of various topical agents and treatment techniques in the decrease of white spot lesions.2,8,12,14,17-35 However, the majority of these studies were conducted using protocols that allow for skewed results due to variability in patient compliance. This same lack of patient compliance is often blamed for the cause of these white spot lesions when considering poor oral hygiene.8,14,15,36 This pilot study was an attempt to lay the foundation for evaluating the efficacy of the treatment agents in a controlled environment, eliminating one of the most difficult variables to monitor: whether or not the patient is actually using the product properly and consistently. By the orthodontist performing the treatment in a controlled environment, compliance was no longer an issue. This was a modest attempt to evaluate how the results compared to the current literature.

In order to properly and effectively evaluate the products and procedures that claim to reverse white spots, it is imperative to minimize variables and control as many factors as possible. The design of this study was intended to do just that; however, a low power was obtained due to the small number of subjects. This could result in making a Type 2 error, or one that is a false negative. Perhaps there really are significant differences, but due to the small sample size, these differences were not picked up on a statistically significant level. There were also wide variations in assessing the data, due to the subjectivity of the measurements, i.e. individual evaluator interpretation of “improvement”. Quantifying results via a surface area percentage comparison as demonstrated by Huang, et al.,29 would prove to standardize data and increase reliability.

In light of perceptions, although most of the subjects failed to note significant changes, they were still pleased with the results of treatment. It is plausible that patients will interpret a variety of treatments as having an influence or change due to the power of suggestion, as seen in a placebo effect. Perhaps it is simply the idea of “having a procedure performed” that aids patients in perception of a change. Without a single drop-out, it could be interpreted that patients and parents see the value of in-office treatments, and shifting the responsibility for compliance away from the patient. One subject reported that she knew she would not follow through with treatment if it was left up to her. The variability in dental expert interpretation of changes in white spots revealed that esthetics are subjective and open to interpretation, even when evaluating the severity of white spot lesions.

Another weakness of the study was the variability in the appearance of the white spots in photographs. Although every photograph was taken in a light-controlled room, inconsistency exists from subject-to-subject, and also within the same subject, but different locations of the mouth. For example, assessing anterior teeth may have been more difficult due to a higher reflection of the flash, resulting in a “washed out” photograph when compared with a buccal view of posterior teeth. While each photograph was only compared directly with a photograph of the same section of the mouth, misinterpretation of severity could skew results.

Another weakness of the study was the variability in the appearance of the white spots in photographs. Although every photograph was taken in a light-controlled room, inconsistency exists from subject-to-subject, and also within the same subject, but different locations of the mouth. For example, assessing anterior teeth may have been more difficult due to a higher reflection of the flash, resulting in a “washed out” photograph when compared with a buccal view of posterior teeth. While each photograph was only compared directly with a photograph of the same section of the mouth, misinterpretation of severity could skew results.

Despite shortcomings inherent in the design of this study, the lack of statistical significance could also be simply due to a true lack of difference between the three products utilized. Perhaps instead of the product itself having a significant effect on the white spots, the technique made more of an impact, albeit small, on the blending of the lesions, softening their appearances. In order to best assess these changes, histological samples could be analyzed. However, this would be impractical for an in vivo study where patient perception is paramount.

Treatment alternatives vary greatly among practitioners. While some products claim to be the superior solution to white spots and other problems, evidence is lacking for all such claims. In fact, some studies imply that improving home care can be the most effective in reducing white spots29. Overall, most orthodontists acknowledge the presence of white spots in a significant percentage of their patients and are attempting to aid in treating them or referring to the general dentist as needed. This survey had a small return rate (5.8%), so universal application of these ideas may be questionable. Nonetheless, the variation in products currently on the market is somewhat a reflection of the findings in current literature. Some studies support the use of MI Paste, while others find fluoride or simply home care to be the best at reversing white spot lesions. As supported in this pilot study, all products can have some effects on white spot lesions; however, none appear to have superior results.

Conclusions

Many products claim to reverse the appearance of white spot lesions. In congruence with the literature, this study lacked evidence to support that any product is superior to regular toothpaste and normal home care. Further studies are needed to determine a difference among white spot treatment alternatives, especially in regard to elimination of patient compliance. The survey of practitioners reflects this same disparity in treatment protocols as seen in the literature.

No statistically significant differences were discovered between any MI Paste, PreviDent 5000 fluoride gel, or the control (Tom’s of Maine non-fluoridated whitening toothpaste).

Subjects reported an improvement in their perceptions of dental appearances due to treatment, and 100% were pleased with the outcome of their treatment.

Orthodontists in private practice observe a significant presence of white spot lesions among their current population (up to 25%), with some finding this number increases to 25%-50% after orthodontic treatment.

Currently, many products and technique alternatives are employed, with the majority of doctors offering some sort of treatment protocol: 47% recommend improved oral hygiene, 48% refer to general dentists if needed. Use of products, such as MI Paste, fluoride, and MI Paste Plus, is fairly equally distributed.

References

1.Summitt JB, Robbins JW, Schwartz RS. Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry: A Contemporary Approach. 3rd ed. Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence; 2006: 2-4.

2.Ogaard B. White spot lesions during orthodontic treatment: mechanisms and fluoride preventive aspects. Semin Orthod. 2008;14(3):183-193.

3.Mizrahi E. Enamel demineralization following orthodontic treatment. Am Journal Orthod. 1982;82(1):62-67.

4.Gorelick L, Geiger AM, Gwinnett AJ. Incidence of white spot formation after bonding and banding. Am J Orthod. 1982;81(2):93-98.

5.Ogaard B, Rolla G, Arends J, ten Cate JM. Orthodontic appliances and enamel demineralization: Part 2. Prevention and treatment of lesions. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;94(2):123-128.

6.Mitchell L. Decalcification during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances–an overview. Br J Orthod. 1992;19(3):199-205.

7.Maxfield BJ, Hamdan AM, Tüfekçi E, Shroff B, Best AM, Lindauer SJ. Development of white spot lesions during orthodontic treatment: perceptions of patients, parents, orthodontists, and general dentists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141(3):337-344.

8.Guzmán-Armstrong S, Chalmers J, Warren J. White spot lesions: prevention and treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138(6):690-696.

9.Derks A, Katsaros C, Frencken JE, van’t Hof MA, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Caries-inhibiting effect on preventive measures during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances: A systematic review. Caries Res. 2004;38(5):413-420.

10.Baysan A, Lynch E, Ellwood R, Davies R, Petersson L, Borsboom P. Reversal of primary root caries using dentifrices containing 5000 and 1100 ppm fluoride. Caries Res. 2001;35(1):41-46.

11.Schirrmeister JF, Gebrande JP, Altenburger MJ, Mönting JS, Hellwig E. Effect of dentifrice containing 5000 ppm fluoride on non-cavitated fissure carious lesions in vivo after 2 weeks. Am J Dent. 2007;20(4):212-216.

12.Alexander SA, Ripa LW. Effects of self-applied topical fluoride preparations in orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2000;70(6):424-430.

13.American Dental Association Council of Scientific Affairs. Caries risk assessment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1151-1159.

14.Benson PE, Parkin N, Millett DT, Dyer FE, Vine S, Shah A. Fluorides for the prevention of white spots on teeth during fixed brace treatment. The Cochrane Collaboration. Wellesley, UK: Wiley & Sons; 2007;3:1-35.

15.Marsh PD. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology. 2003;149(Pt 2):279-294.

16.Kimmel L, Tinanoff N. A modified mitis salivarius medium for a caries diagnosis test. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6(5):275-279.

17.Anderson MH. A review of the efficacy of chlorhexidine on dental caries and the caries infection. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31(3):211-214.

18.Emilson CG, Linquist B, Wennerholm K. Recolonization of human tooth surfaces by streptococcus mutans after suppression by chlorhexidine treatment. J Dent Res. 1987;66(9):1503-1508.

19.Scheinin A, Mäkinen KK, Ylitalo K. Turku sugar studies: V. Final report on the effect of sucrose, fructose and xylitol diets on the caries incidence in man. Acta Odonto Scand. 1976;34(4):179-216.

20.Mäkinen KK, Bennett CA, Hujoel PP, Isokangas PJ, Isotupa KP, Pape HR Jr, Mäkinen PL. Xylitol chewing gums and caries rates: a 40-month cohort study. J Dent Res. 1995;74(12):1904-1913.

21.Zimmer S, Robke FJ, Roulet JF. Caries prevention with fluoride varnish in a socially deprived community. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27(2):103-108.

22.Isokangas P, Alanen P, Tiesko J, Mäkinen KK. Xylitol chewing gum in caries prevention: a field study in children. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;117(2):315-320.

23.Dawes C, Macpherson LM. Effects of nine different chewing gums and lozenges on salivary flow rate and pH. Caries Res. 1992;26(3):176-182.

24.Aimutis WR. Bioactive properties of milk proteins with particular focus on anticariogenesis. J Nutr. 2004;134(4):989S-95S.

25.Tung MS, Eichmiller FC. Dental applications of amorphous calcium phosphates. J Clin Dent. 1999;10(1 Spec No):1-6.

26.Iijima Y, Cai F, Shen P, Walker G, Reynolds C, Reynolds EC. Acid resistance of enamel subsurface lesions remineralized by a sugar-free chewing gum containing casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. Caries Res. 2004;38(6):551-556.

27.Azarpazhooh A, Limeback H. Clinical efficacy of casein derivatives: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(7):915-924, 994-995.

28.Tung MS, Eichmiller FC. Dental applications of amorphous calcium phosphates. J Clin Dent. 1999;10(1 Spec No):1-6.

29.Huang GJ, Roloff-Chiang B, Mills BE, Shalchi S, Spiekerman C, Korpak AM, Starrett JL, Greenlee GM, Drangsholt RJ, Matunas JC. Effectiveness of MI Paste Plus and PreviDent fluoride varnish for treatment of white spot lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop. 2013;143(1):31-41.

30.Robertson MA, Kau CH, English JD, Lee RP, Powers J, Nguyen JT. MI Paste Plus to prevent demineralization in orthodontic patients: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop. 2011;140(5):660-668.

31.Knösel M, Attin R, Becker K, Attin T. External bleaching effect on the color and luminosity of inactive white-spot lesions after fixed orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2007;77(4):646-652.

32.Shungin D, Olsson AI, Persson M. Orthodontic treatment-related white spot lesions: A 14-year prospective quantitative follow-up, including bonding material assessment. Am J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop. 2010;138(2):136 e1-8, 136-137.

33.Kohda N, Iijima M, Brantley W, Muguruma T, Yuasa T, Nakagaki S, Mizoguchi I. Effects of bonding materials on the mechanical properties of enamel around orthodontic brackets. Angle Orthod. 2012;82(2):187-195.

34Murphy TC, Willmot DR, Rodd HD. Management of postorthodontic demineralized white lesions with microabrasion: a quantitative assessment. Am

J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop. 2007;131(1):27-33.

35.Mitchell L. An investigation into the effect of a fluoride releasing adhesive on the prevalence of enamel surface changes associated with directly bonded orthodontic attachments. Br J Orthod. 1992;19(3):207-214.

36.Brenson PE, Pender N, Higham SM, Edgar WM. Morphometric assessment of enamel demineralisation from photographs. J Dent. 1998;26(8):669-677.

37.Artun J, Thylstrup A. A 3-year clinical and SEM study of surface changes of carious enamel lesions after inactivation. Am J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop.

1989;95(4):327-333.

38.Knosel M, Bojes M, Junk K, Ziebolz D. Increased susceptibility for white spot lesions by surplus orthodontic etching exceeding bracket base area. Am

J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop. 2012;141(5):574-582.

39.Ogaard B. Prevalence of white spot lesions in 19-year-olds: a study on untreated and orthodontically treated persons 5 years after treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofaical Orthop. 1989;96(5):423-427.

40.Landsberger H. Hawthorne Revisited. Ithaca, NY: The New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations; 1958: 132.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores