CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss a digital platform that fully customizes tooth movement with the 3D-printed bracket system.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Recognize various types of indirect bonding.

- Realize some disadvantages of the traditional indirect bonding technique.

- Realize some advantages of the 3D-printed bracket technology.

- Recognize how to reduce human error in IDB tray fabrication by 3D-printing technology.

- Recognize the need for minimization of the amount of bonding cement.

Dr. Alfred C. Griffin Jr. discusses how technology led him back to indirect bonding

As an orthodontist in practice for over 35 years, I have seen many changes in the way we practice. I entered the profession well after the integration of “prescription brackets” into the orthodontic armamentarium, and bonded brackets had been around for a long while. I’ve been through many iterations of how best to place the bracket on the dentition. During my residency at the Eastman Dental Center, I remember asking Dr. Lawrence F. Andrews himself where the bracket was supposed to be placed, and he responded simply, “in the middle of the tooth.” We used height gauges, but I quickly discovered that the same gauge and millimeter measurement did not fit the same tooth on every patient, and eventually abandoned the gauge for “eyeballing it.”

Indirect bonding was introduced in the 1980s as a method of placing brackets on the teeth in a more accurate and efficient way.1-3 Many different variants of indirect bonding have been introduced over the years, from the initial efforts of placing brackets after drawing scribe lines on study model teeth and adhering the brackets on the models with “Sugar Daddy” candy up to modern-day 3D printing of the transfer trays and subsequent loading of the brackets into the independently created trays.3-5 (Editor’s note: “Sugar Daddy” technique was proposed by Swartz in 1974, using caramel candy as an adherent to place brackets to models. After the final trays have been completed, the caramel-candy water-soluble material was removed from the back of bracket base, and mesh pads were exposed for bonding in the clinic. The clean base method with a single silicone delivery tray is the original technique used in indirect bonding.”6)

On at least four different occasions, I have changed my office bonding systems to indirect bonding only to revert back to direct bonding. Each time I went to indirect bonding, I found it more cumbersome and/or less accurate due to the many variables involved in the process. The original goal of indirect bonding was to be both more efficient and more accurate. Several research efforts did not support the enhanced accuracy benefit.1-3 In an American Association of Orthodontists article published in September 1999 on the accuracy of direct versus indirect bonding, Koo, Chung and Vanarsdall stated, “Our results indicated that both direct and indirect bonding techniques failed to execute ideal bracket placement.”2

The past few years have brought what I believe to be the greatest advances in fixed appliances since the prescription brackets of the 1970s. Today with the wedding of enhanced software capabilities and 3D printing of ceramic brackets such as LightForce™ Orthodontics brackets (Cambridge, Massachusetts), we no longer have to accept the “one-size-fits-all” concept of traditionally manufactured brackets. The new biomechanical treatment advantages of full-customization (base + slot) have been illustrated in recent articles and forums. While 3D-printed brackets have taken the spotlight, it is the application of novel 3D-software algorithms that has drastically improved the efficacy of indirect bonding in terms of increased efficiency and accuracy in our office. (Editor’s note: The author reports that, currently, to his knowledge, there are no other fully customized 3D-printed brackets manufactured anywhere. He adds that some manufacturers provide different torque values, depending on the treatment plan (KLOwen™, Fort Collins, Colorado), and some have manufactured customized slots welded to stock bases, but no other bracket has a customized slot and base that is manufactured to exactly fit the individual tooth morphology.)

When I first started using 3D-printed ceramic brackets, I did so despite my trepidation about the indirect bonding delivery system (IDB). I was fortunate to be an early adopter of this 3D-printed bracket technology and was able to voice my many concerns about IDB in general. Four years later, it is my preferred way of delivering fixed appliances. All of my former problems with IDB were a function of the human error inherent in the fabrication of the IDB trays and subsequent delivery — from the need to still “eyeball” the placement of the bracket on models to the manual fabrication of the IDB tray on the bracketed models and the subsequent removal of the IDB tray from the models, hopefully with the brackets still in place.

The delivery appointment was also fraught with peril. Was the tray seated correctly? Did I manually place enough finger pressure both occlusally and labially/buccally to get the brackets where they belong? In which direction do I remove the tray, and when I remove the tray, will it come off in one piece? My journey from skepticism to enthusiasm for IDB is the result of the application of sophisticated software development paired with 3D-printing capabilities. I will go through the entire process so that I can illuminate the differences between “then” and “now.”

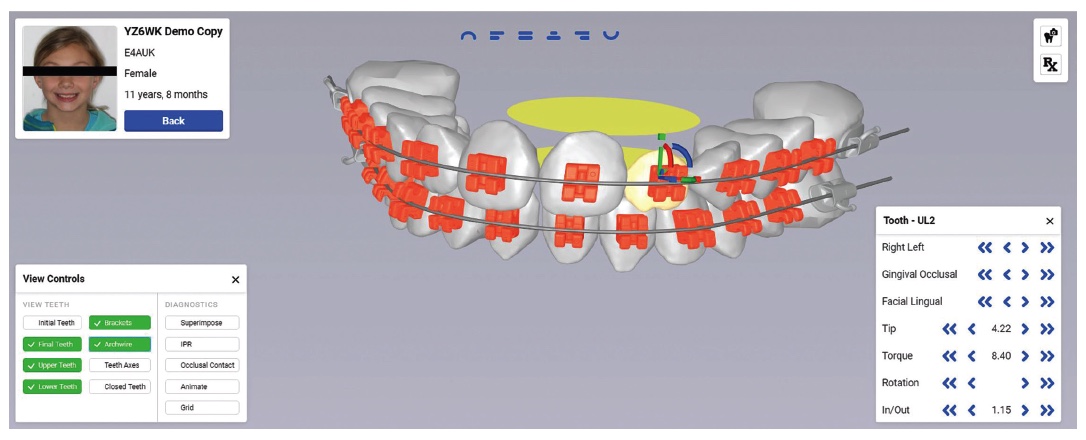

In my opinion, the placement of an orthodontic bracket on a tooth in its ideal position is of the highest importance to successful treatment outcomes. Up to now, it has always involved human placement, either directly on the tooth or on a model for transfer to the natural dentition via a transfer tray. Today with virtual treatment planning software for 3D-printed ceramic brackets, we have the capability to define the longitudinal and latitudinal axes of a tooth in an automated fashion and maintain that the bracket face remains parallel to this facial axis (FA) point, regardless of where it is placed. Therefore, unlike standard, “off-the-shelf” bracket systems, 3D-printed brackets do not need to be placed directly on FA point. Rather, an offset in the base is created to allow the appliance to be bonded anywhere on the labial surface. The slot orientation automatically changes to deliver the same direction of force as if it were centered on the tooth. Such “offset” positions are used to avoid occlusal interferences or to bond to severely rotated or blocked-out teeth. Automated assistance in bracket placement like this eliminates one of the most common hindrances to accurate tooth positioning and is only possible via 3D printing.

Unlike stock orthodontic brackets, 3D-printed brackets are actually designed and fabricated to be delivered via IDB tray, so that both adherence in the tray and subsequent tray removal with brackets remaining on the dentition can be optimized. A custom release angle is designed into every IDB segment (Figure 1). Also, instead of the IDB trays being fabricated over the bracketed study models, the IDB trays are independently fabricated by 3D-printing methodology. This eliminates the human error in IDB tray fabrication and the occasional bracket displacement during the tray fabrication. This process also creates a uniform transfer tray in terms of thickness, shape, and material consistency. Combined with the ability to design the 3D-printed ceramic bracket to be compatible with IDB transfer, this lends itself to a much more reliable and consistent chairside procedure.

Initially we tried many iterations of the 3D-printed IDB tray, from whole arch to half arch to segmented arches. We found the segmented arches (right and left posterior and an anterior section for upper and lower arches) to be most consistent (Figure 2). Material consistency and dimensional exactness lent itself to reproducible results with one exception. We found that the inciso-gingival positioning varied more than we would prefer. This was due to a lack of vertical stop of the incisors in the anterior segments. Because of the accuracy of 3D printing, we were able to design the anterior segments with occlusal rests on the cuspids on the palatal without any interference from the cuspid brackets already bonded on the labial surface. This gave enhanced vertical support to the anterior segments and led to much more consistency of placement of the anterior trays in all dimensions.

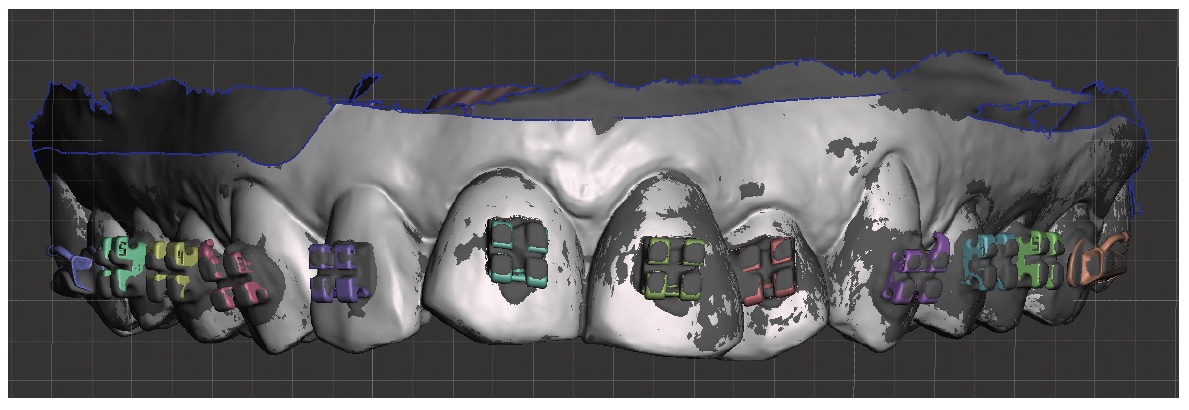

I bonded my first cases of 3D-printed ceramic brackets and was very pleasantly surprised at the ease and perceived accuracy of the bracket placement. Next, I wanted to test the position of the brackets on the patient’s teeth compared to the virtual position I had approved through the LightPlan software setup (Figure 4). I therefore bonded the next five IDB cases myself and had my assistants immediately scan the patients before archwires were placed. I subsequently sent these post placement scans back to LightForce™ and asked them to super-impose the post placement scans over the prefabrication virtual setup images (Figure 5). Every one of the pre- and post-scans superimposed perfectly, thus proving to me the exact transfer of bracket positioning from the virtual setup to the patient’s dentition.

I bonded my first cases of 3D-printed ceramic brackets and was very pleasantly surprised at the ease and perceived accuracy of the bracket placement. Next, I wanted to test the position of the brackets on the patient’s teeth compared to the virtual position I had approved through the LightPlan software setup (Figure 4). I therefore bonded the next five IDB cases myself and had my assistants immediately scan the patients before archwires were placed. I subsequently sent these post placement scans back to LightForce™ and asked them to super-impose the post placement scans over the prefabrication virtual setup images (Figure 5). Every one of the pre- and post-scans superimposed perfectly, thus proving to me the exact transfer of bracket positioning from the virtual setup to the patient’s dentition.

Up to this point in my practice, I had placed every bracket on every patient myself, either directly or indirectly. With this newfound confidence in the transferability of the 3D-printed brackets with the 3D-printed IDB trays, I decided to have my assistants perform this task without my participation. State laws vary on this, so orthodontists need to check on the regulations that adhere to specific state guidelines.

Again, after bracket placement, this time completely accomplished by an assistant, we took post bonding scans and asked for superimpositions. Again, there was exact superimposition between the pretreatment virtual setup and the post bonding patient scan.

Today all of my IDB with this system is accomplished by my assistants, and I am confident that their capabilities to deliver exact bracket placement are equal to mine. This has allowed me to spend more time within the practice focused on diagnosis, treatment planning, and patient and parent management, while still feeling secure that the most important clinical procedure on our schedule is being accomplished in a superior fashion.

3D-printed ceramic brackets with customized prescriptions to the individual patient’s anatomy and treatment plan have been introduced into several orthodontic residency programs. I am a part-time faculty member in the orthodontic department at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, and when we introduced the LightForce System, we had a first-year resident with almost no real clinical experience bond the first case. I was there to oversee the procedure, but she performed the entire bonding process herself. Again, exact placement was achieved.

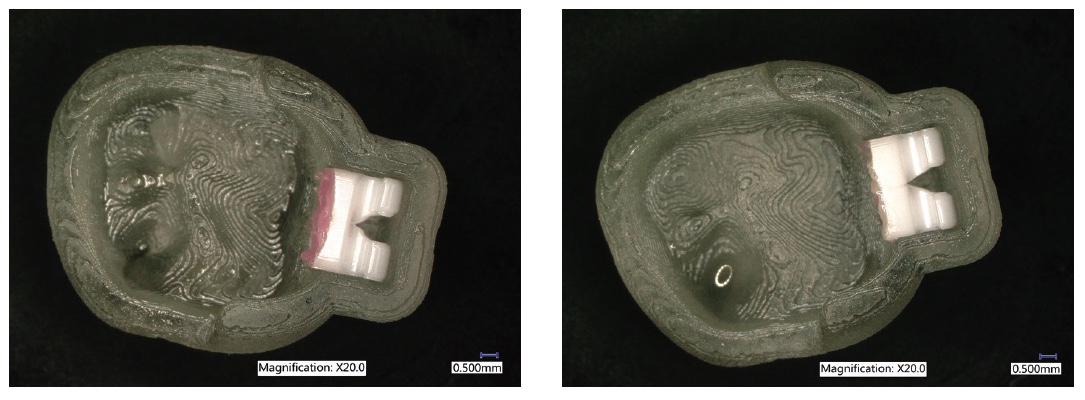

Probably the most difficult part of bonding the customized 3D-printed brackets is the minimization of the amount of bonding cement needed. Remember, these bases are also customized and an exact mirror to the specified labial surface of that particular tooth (Figure 6). My advice to residents is to place the thinnest volume of bonding material possible while still covering the whole pad. One can use any type of light-cured orthodontic bonding material. The important point is to use the least amount possible (Figure 7).

Despite the minimal amount of bonding material used, I would expect to see more consistency of bond strengths due to the more uniform thickness of adhesive throughout the tooth-bracket pad interface. The “breakaway” design of these bases also delivers a consistent bracket removal at debonding time.

This is an exciting time to be practicing orthodontics. The advances in software design and 3D printing have allowed a true customization of fixed appliance therapy that is predicated on our patients’ individuality. It has also led to much greater efficiencies in our office routine that allow the doctor to focus on diagnosis and treatment planning and the communication of that knowledge to our patients and families. That is what separates us from non-orthodontist care providers.

The topic of this webinar is adapting to the advanced IDB bonding system using a 3D bracket system. Check out how to use a digital workflow for bracket treatment here.

https://orthopracticeus.com/webinar/webinar-with-dr-alexander-waldman-and-dr-alfred-griffin-iii/

References

- Hodge TM, Dhopatkar AA, Rock WP, Spary DJ. A randomized clinical trial comparing the accuracy of direct versus indirect bracket placement. J Orthod. 2004;31(2):132-137.

- Koo BC, Chung CH, Vanarsdall RL. Comparison of the accuracy of bracket placement between direct and indirect bonding techniques. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116(3):346-1351.

- Li Y, Mei L, Wei J, et al. Effectiveness, efficiency, and adverse effects of using direct or indirect bonding technique in orthodontic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2019;8;19(1):137.

- Schmid J, Brenner D, Recheis W, Hofer-Picout P, Brenner M, Crismani AG. Transfer accuracy of two indirect bonding techniques — an in vitro study with 3D scanned models. Eur J Orthod. 2018; 40(5)549-555.

- Grünheid T, Lee MS, Larson BE. Transfer accuracy of vinyl polysiloxane trays for indirect bonding. Angle Orthod. 2016;86(3):468-474. Epub 2015 September 10.

- Aggarwal P, Aggarwal R. Indirect Bonding Procedures in Orthodontics – A Review. J Dents Dent Med. 2018;1(4):120. https://www.boffinaccess.com/open-access-journals/journal-of-dentistry-and-dental-medicine/jddm-1-120.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2020.

Dr. Alfred C. Griffin Jr., DDS, is a practicing orthodontist in Virginia since 1982. He received his bachelor’s degree in Biology and Psychology at the University of Virginia before attending the Medical College of Virginia for his DDS and completing his Residency at Eastman Dental Center. A member of Georgetown University School of Dentistry for 8 years, he has also been an active faculty member of Harvard School of Dental Medicine since 2015.

Dr. Alfred C. Griffin Jr., DDS, is a practicing orthodontist in Virginia since 1982. He received his bachelor’s degree in Biology and Psychology at the University of Virginia before attending the Medical College of Virginia for his DDS and completing his Residency at Eastman Dental Center. A member of Georgetown University School of Dentistry for 8 years, he has also been an active faculty member of Harvard School of Dental Medicine since 2015.