CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss the various forms of harassment and substance abuse and how to avoid putting clinicians, staff, and patients in unlawful situations.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Define the conduct that constitutes harassment.

- Identify some classifications of harassment and how to avoid them in the practice environment.

- Define substance abuse.

- Realize which drugs are most easily abused and how to avoid the pitfalls.

- Realize the challenges that dentists face when patients “vape.”

- Recognize the legal and ethical challenges when the clinician has substance abuse issues and possible measures if such abuse is noted in the office

Dr. Bruce H. Seidberg discusses various forms of harassment and substance abuse

Introduction

Part 1 of this series focused primarily on the dentist-patient relationship, informed consent, and documentation of treatment. Part 2 focuses on two other areas of dental practice that intersect with the law. The first is harassment, which deals with the demeanor of those within the practice, including the dentist, employees, and patients. The second has been summarized from a very broad area that includes, but is not limited to, use of drugs, prescribing drugs, alcohol, vaping, and self-infliction — all of which can lead to the loss of license and/or family, and even death.

Part 1 of this series focused primarily on the dentist-patient relationship, informed consent, and documentation of treatment. Part 2 focuses on two other areas of dental practice that intersect with the law. The first is harassment, which deals with the demeanor of those within the practice, including the dentist, employees, and patients. The second has been summarized from a very broad area that includes, but is not limited to, use of drugs, prescribing drugs, alcohol, vaping, and self-infliction — all of which can lead to the loss of license and/or family, and even death.

Harassment

Harassment is the conduct of one individual directed to another that would cause a reasonable person’s interpretation that there is a credible threat to a person’s safety or to that of his/her family or fear in his/her place in the workforce. The workforce is a universal situation involving any form of employment, but this article focuses on the health field environments of dentistry, medicine, and hospitals. Harassment occurs more often than is readily made known, primarily because of the fear of reporting it or the lack of action by those to whom it is reported. This is a source of frustration for victim advocates and members of the criminal justice system.1

The ADA absolutely prohibits sexual harassment and harassment on the basis of race, color, religion, gender, national origin, age, disability, sexual orientation, status with respect to public assistance, or marital status. Certain discriminatory harassment is prohibited by state and federal laws, which may subject the ADA and/or the individual harasser to liability for any such unlawful conduct. With this policy, the ADA prohibits not only unlawful harassment but also other unprofessional and discourteous actions. Derogatory racial, ethnic, religious, age, sexual orientation, sexual, or other inappropriate remarks, slurs, or jokes will not be tolerated. Sexual harassment includes unwelcome sexual advances and requests for sexual favors, and all other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature. Harassment is against the law.2

Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination and, therefore, illegal under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act 31,32. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, or age in hiring, promoting, firing, setting wages, testing, training, apprenticeship, and all other terms and conditions of employment. Harassment claims, allegations, and lawsuits are popular areas of compliance violations in employment law. There has been an increase of reported harassment of various types within the past 5 years.5

There are several classifications of “harassment”6 (Table 1). Each one has its own characteristics, and each one is punishable. The #MeToo movement that has been prevalent the past few years has focused on sexual abuse,7 the most common form of the harassment categories. It is the unwelcome verbal, visual, or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is severe or pervasive and can affect working conditions or create a hostile work environment. Sexual misconduct occurs more frequently than reported, and of those reported, most are not successfully prosecuted because of lack of sufficient evidence made available for the egregious allegations.8 Allegations for sexual harassment include but are not limited to, those listed in Table 2.8 Allegations of being forced to work in an office environment filled with references, material, gestures, and discussions, which included being forced to endure pornographic materials in print, magazine, and digital form, and being subjected to unwelcome touching by the dentist while making inappropriate sexual comments lead to a hostile harassment environment.9,10 The New York State Dental Association addressed this issue in 1995.11 One of the most egregious cases was in 2009 in which a dentist claimed that massaging women’s chest muscles was treatment to relieve TMD symptoms.12

Quid pro quo harassment is a request for “this” for a result for “that.” It generally results in a tangible employment decision based upon the employee’s acceptance or rejection of unwelcome sexual advances or requests for sexual favors, but it can also result from unwelcome conduct that is of a religious nature. This kind of harassment is generally committed by someone who can effectively make or recommend formal employment decisions (such as termination, demotion, or denial of promotion) that will affect the victim — i.e., a supervisor who fires or denies promotion to a subordinate for refusing to be sexually cooperative. A female employee who accused a supervisor for forcing her into sex was then being fired after she refused.13

Quid pro quo harassment is a request for “this” for a result for “that.” It generally results in a tangible employment decision based upon the employee’s acceptance or rejection of unwelcome sexual advances or requests for sexual favors, but it can also result from unwelcome conduct that is of a religious nature. This kind of harassment is generally committed by someone who can effectively make or recommend formal employment decisions (such as termination, demotion, or denial of promotion) that will affect the victim — i.e., a supervisor who fires or denies promotion to a subordinate for refusing to be sexually cooperative. A female employee who accused a supervisor for forcing her into sex was then being fired after she refused.13

Verbal abuse is the second most common type of harassment reported. It includes any type of inappropriate communication such as a one to one, electronic, or telephonic. Typically, it involves lewd comments, off-color jokes, comments about appearance or body parts, being disciplined in front of patients or other staff, and use of harsh tones. The perception of patients is that of a non-caring, non-compassionate, and non-professional dentist. Verbal abuse is demeaning and embarrassing.

Physical abuse is that of inappropriate unwanted touching or threatening whereby the individual feels threatened of being harmed. Physical harassment can be in the form of assault and battery. When a reasonable person fears that he/she is threatened to be touched in an unwanted manner, it is assault; and when a reasonable person is actually restrained and touched, it is battery.

Harassment has consequences such as a negative effect on an office and its personnel. Harassment makes the office atmosphere “stale” and unhappy, can cause a loss of patients, and create a rotating door for staff instability, can be a potential loss of jobs and/or license, and tarnishes family relationships. Harassment of any type violates the law specifically because of its abusive nature to the person affected, and if severe and pervasive enough, it creates a work environment that a reasonable person would find hostile.

Harassment has consequences such as a negative effect on an office and its personnel. Harassment makes the office atmosphere “stale” and unhappy, can cause a loss of patients, and create a rotating door for staff instability, can be a potential loss of jobs and/or license, and tarnishes family relationships. Harassment of any type violates the law specifically because of its abusive nature to the person affected, and if severe and pervasive enough, it creates a work environment that a reasonable person would find hostile.

For protection, every office should have a “no tolerance” harassment policy that encourages employees to complain about sexual harassment, assure employees that their complaints will be handled in a confidential manner, and outline reporting channels and methods. Always have an assistant in an operatory when treating patients. Never scold, belittle, or raise your voice to an assistant. Use common sense, and offer constructive criticism in the appropriate setting, and remember that compliments should not contain sexual innuendos.

Substance abuse

Occasional use of legal or illicit drugs usually used in a social setting and rarely causing harm or threat of harm to self or others is considered to be substance use. Occasional use in situations that can cause harm to self or others is considered substance misuse. Either category, use or misuse, can include the occasional drink at a party or meeting, but excessive alcoholic drinks are misuse that can lead to intoxication and a DWI.

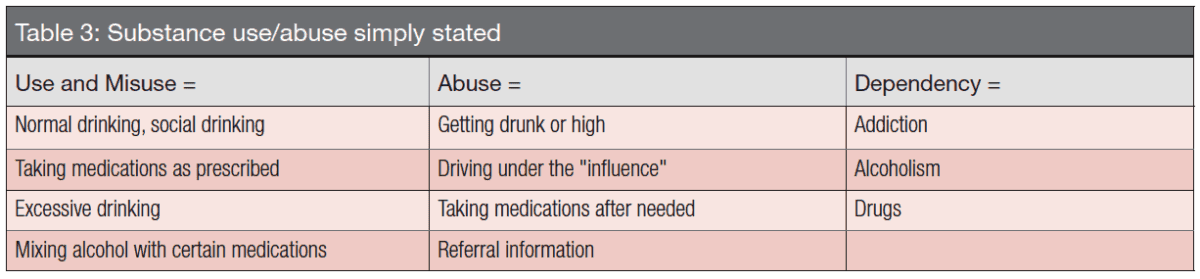

Misuse of prescription drugs means taking a medication in a manner or dose other than prescribed; taking someone else’s prescription, even if for a medical complaint such as pain; or taking a medication to feel euphoria, i.e., to get high. The term “nonmedical use of prescription drugs” also refers to these categories of misuse.14 Substance abuse, a third classification, is a pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. There is a capacity to control the use of substances in the aforementioned. When individuals are unable to stop using a substance, when they lack capacity to control use despite self-knowledge that the problems are caused by continued substance use, they are considered to be substance-dependent (Table 3). When those in dependency are asked why, they claim for the feeling of euphoria, to reduce perceived stress, or just to feel better. This type of individual can also be referred to as having an addiction. Addiction is characterized by the inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control and craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behavior and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response.14 The health professions are now engaged in attempting to stop opioid addiction by educating those who prescribe drugs.

Drugs include, but are not limited to, overuse and misuse of prescribed medications; all of the opioids, which are referred to daily in the media; nicotine (tobacco); and vaping substances, alcohol, and nitrous oxide. Use of nitrous oxide is easily available in dental offices and is most abused in the dental field.14 It is the leading cause of death in a dental office. Using prescription pain relievers with other prescription drugs (i.e., antidepressants) or over-the-counter medications (i.e., cough syrups and anti-histamines) can lead to life-threatening respiratory failure. With some pain relievers, all it takes is one pill.

Drugs include, but are not limited to, overuse and misuse of prescribed medications; all of the opioids, which are referred to daily in the media; nicotine (tobacco); and vaping substances, alcohol, and nitrous oxide. Use of nitrous oxide is easily available in dental offices and is most abused in the dental field.14 It is the leading cause of death in a dental office. Using prescription pain relievers with other prescription drugs (i.e., antidepressants) or over-the-counter medications (i.e., cough syrups and anti-histamines) can lead to life-threatening respiratory failure. With some pain relievers, all it takes is one pill.

The overprescribing and use and dangers of opioids have been widely publicized, and the tobacco industry has had its fair share of negative publicity.14 The opioid and tobacco industries have faced numerous product liability claims. Recently, the media have reported numerous cases of vaping that have caused respiratory issues from severe to fatal. What has not been reported in depth is the questionable use of recreational or illicit marijuana, CBD products, cannabis, and e-cigarettes.14

The overprescribing and use and dangers of opioids have been widely publicized, and the tobacco industry has had its fair share of negative publicity.14 The opioid and tobacco industries have faced numerous product liability claims. Recently, the media have reported numerous cases of vaping that have caused respiratory issues from severe to fatal. What has not been reported in depth is the questionable use of recreational or illicit marijuana, CBD products, cannabis, and e-cigarettes.14

Issues now surfacing (that readers of this article are encouraged to seek out) are the true issues that face children today, especially those of vaping. Vaping is getting out of control starting in middle school. Now there is VAPRWEAR, technology-developed clothing, and other means for vaping without being seen.14 The news media have reported on a number of deaths and other respiratory problems associated with vaping.

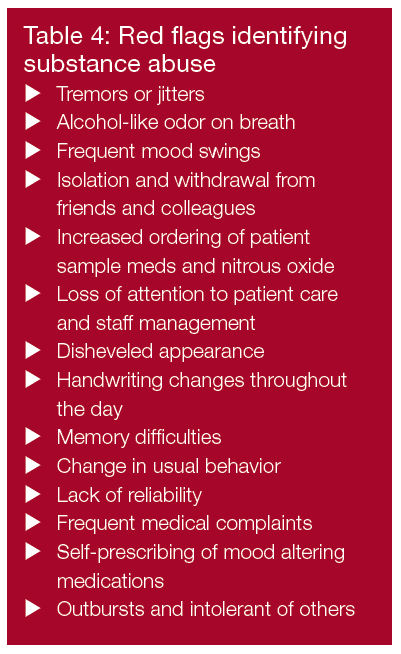

Dental provider substance abusers are usually less productive, more likely to stop work earlier than normal, more likely to be late for work, and found to be more irritable and have frequent mood changes in and outside of the office. Red flags to help identify substance abusers are found in Table 4.

The dental profession is cautioned to be diligent in prescribing habits when participating in the prevention of drug abuse by patients. Drugs should only be used as an adjunct to the dental treatment. Pain management drugs include non-narcotic analgesics (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) or opioids (i.e., narcotics). Opioid prescription pain medications are a type of medicine used to relieve pain. Some of the common names include oxycodone and acetaminophen (Percocet®), oxycodone (OxyContin®), and hydrocodone and acetaminophen (Vicodin®). The three most commonly abused prescribed drugs involved in overdose death are hydrocodone, oxycodone, and methadone. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) provide excellent pain relief due to their anti-inflammatory and analgesic action. Most painful problems that require analgesics will be due to inflammation.

It is unethical for a dentist to practice while abusing controlled substances, alcohol, or other chemical agents that impair the ability to practice.17 All dentists have an ethical obligation to urge chemically impaired colleagues to seek treatment. Dentists with first-hand knowledge that a colleague is practicing dentistry when so impaired have an ethical responsibility to report such evidence to the professional assistance committee of a dental society.18

Failure to adequately warn patients about morbidity or to have screenings for risk factors such as psychosis when prescribing high-potency pain medications could leave dentist vulnerable to malpractice litigation.19 Drug use by anyone is self-abuse, life abuse, and the potential destruction of life.

Summary

Every office should have a harassment policy with which all employees are familiar and comfortable. Always act professionally, and avoid the off-color humor with staff and patients. Attempt to never be alone in the operatory with a patient, especially one of the opposite gender. Prescribe only what is necessary when necessary and only to your patients of record. Prescribe minimally, and try to avoid the opioid crisis. Be aware of substance use, misuse, and abuse of alcohol and drugs. Take time to educate staff and patients about the dangers of vaping and the effects on dental health.

Conclusion

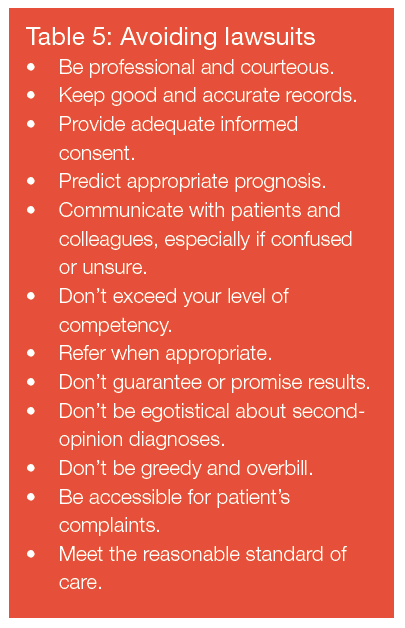

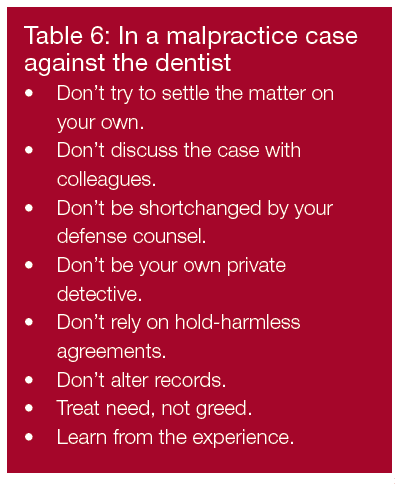

A successful practitioner should adhere to Mickey Fallon 3A’s Doctrine of Affability, Availability, and Ability.20 Affability is to be easy to speak to, approachable, amicable, and gentle. Availability is to be accessible to anyone in need for whatever reason. Ability is to be able to think, to accomplish, and have the mental or physical power to do something and to do it well and all in that order. Following the principles of risk management listed in Table 5 will help avoid lawsuits. In the event of being involved in a lawsuit, follow the criteria set forth in Table 6. Always act morally, ethically, professionally, and with integrity.2

In addition to harassment, Dr. Seidberg explored risk management in the dental office in part 1 of this series. Read it here (and subscribers can take the quiz to obtain 2 CE credits). https://orthopracticeus.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/28-31_CE-Seidberg.pdf

References

- Campbell R., Patterson D. Bybee Prosecution of adult sexual assault cases: a longitudinal analysis of the impact of a sexual assault. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(2):223-244.

- American Dental Association (ADA). Sexual Harassment and the Dental Workplace. Unit 3. Appendix 3.2; 2017. Unit 3 Appendix 3_2_harassment.docx. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Guidelines on Sexual Harassment, 29 C.F.R. Section 1604.11; 1980. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/29/1604.11 Accessed February 25, 2020.

- Weinstein BD. Sexual harassment: identifying it in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125(7):1016-1021.

- Twigg T, Crane R. Harassment: avoiding the nightmare. Dental Economics. 2010. https://www.dentaleconomics.com/practice/article/16392775/harassment-avoiding-the-nightmare. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- Seidberg BH. Harassment — Crossing the Professional Line. Endodontic Practice US. 2013;6(5)42-45.

- Zener K. What’s A Dentist To Do? And Other Boundaries Issues. ACLM 12th Annual Ethics and Legal Aspects of Dentistry Conference. Los Angeles, CA. 2019.

- Seidberg BH. Harassment — Crossing the Professional Line. Oral Health. 2014;10-14.

- Ashbury K Stone v Howard & Howard DDS. Kanawha Circuit Court, case no. 09-C-2103. West Virginia Legal Journal.

- Campbell R, Patterson D, Bybee D. Prosecution of adult sexual assault cases. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(2):223-244

- New York State Dental Association. Policy Statement: Sexual Harassment in the Professional Workplace. Albany, NY. 1995

- Associated Press. Woodland Dentist Faces Sexual Harassment Charges. February 2009

- Bradon C. Woman accuses supervisor of forcing her into sex, firing her after she refuses. Ferrell v Matthew. Kanawha County Circuit Court; Case No. 19-c-806, 2018. West Virginia Record. September 2019. https://wvrecord.com/stories/513840481-woman-accuses-supervisor-of-forcing-her-into-sex-firing-her-after-she-refuses. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- Bornstein E. Opioids and Marijuana: Managing the Nationwide Emergency. INR Seminars. September 2019. Syracuse, NY

- Seidberg BH. Dentist’s Drug Use, Abuse and Dependency. Syllabus. American College of Legal Medicine. 2004

- Arnold J. Knowing the Risks of Opioid Prescription Pain Medication https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/mtgs/pract_awareness/conf_2018/sept_2018/arnold.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- American Dental Association (ADA). Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct. Section 2, 2.d. Personal Impairment. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/Ethics/Code_Of_Ethics_Book_With_Advisory_Opinions_Revised_to_November_2018.pdf?la=en. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- Seidberg BH. Ethics, Morals, the Law and Endodontics. In: Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner JC, eds. Ingle’s Endodontics 6. 6th ed. Lewiston, NY: BC Decker; 2008.

- Seidberg BH, Sullivan TH. Dentists’ use, misuse, abuse or dependence on mood-altering substances. N Y State Dent J. 2004;70(4):30-33.

- Fallon MW. Personal communication. Oral maxillo-facial surgeon. Syracuse, NY; 2002.

- Seidberg BH. Ethics, Morals, and Law in the Professional Office. Endodontic Practice US. 2014.