CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss orthodontists’ and laypersons’ esthetic preferences in different occlusions.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions with the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify traditional ideal treatment goals for occlusion and jaw relationships.

- Realize the differences between how orthodontists and laypersons view facial esthetics.

- Recognize various ways to assess soft tissue facial profile.

- Identify how to determine if a large mandibular advancement or a small mandibular advancement changes esthetics ratings from a frontal view and three-quarter view perspective.

- Recognize differences in the resultant esthetics of the male subjects versus female subjects.

Drs. Jeffrey H. Lee, Daniel Rinchuse, Thomas Zullo, and Lauren Sigler Busch investigate how the advancement of the mandible changes facial esthetics from a frontal and three-quarter view

Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to investigate orthodontists’ esthetic preferences compared to laypersons when manipulating the anteroposterior position of the mandible from a retruded mandibular position (maximum intercuspation) to a protruded position (with a maximum 6 mm advancement of the mandible) in a frontal and three-quarter profile view.

Method

One male and one female target persons were selected based on the inclusion criteria for the study. These target persons were evaluated by a small group of laypersons and rated for average attractiveness to participate in the study. Each target person had a wax bite taken for each mandibular advancement positions (0 mm, 2 mm, and 6 mm advancements from maximum intercuspation) and had his/her photograph taken from these positions from a frontal view and a three-quarter profile view. A total of 12 photos were manipulated for evaluation, with two duplicate photos taken for reliability. The raters were comprised of 10 orthodontists and 152 laypersons who rated each of the photos for its attractiveness level. Using SPSS software, a 2x2x3x2 ANOVA was performed to test whether there were statistically significant differences between the “main effects” (gender, view, mandibular position, and judge group) and the “interaction effects” with each of the main effects (i.e., gender x mandibular position, gender x view, etc.).

Results

There were statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences for the gender and view categories. In addition, there were statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences among the interaction effects for both (gender x view) and (gender x mandibular position), but both interaction effects were slightly under-powered (0.555 and 0.606).

Conclusions

There was more esthetic preference for the female target person and for the frontal view photos. Intrajudge reliability showed that orthodontists were inconsistent with their ratings versus laypersons. Interjudge reliability for the orthodontists was good (0.736).

Background

In traditional orthodontics, ideal treatment goals were to obtain Angle’s Class I dental occlusion and jaw relationships.1,2,3 This focus shifted in contemporary orthodontics to a soft tissue paradigm and smile esthetics.4,5,6 Since esthetics plays a key role in orthodontic treatment, numerous studies have been performed to evaluate facial attractiveness utilizing silhouettes of profiles,2,4 digital imaging alterations to simulate esthetic alterations,5,6,7,8 as well as bite blocks or functional appliances to alter the position of the mandible.7,8,9,10,11 Other studies have examined the improvement of soft tissue profile changes after orthognathic surgery with mandibular advancement.4,12

Orthodontists have used cephalo-metrics for decades to assess the soft tissue facial profile as part of their diagnosis.6,13 The information that cephalometric X-rays provide is only part of the records collection, since proper diagnosis also requires a panoramic film, model casts, and soft tissue analyses.14 In addition, orthodontists lack a comprehensive rubric for soft tissue analysis when compared to Angle’s classes of dental malocclusions or cephalometrics for skeletal measurements. Soft tissue analysis is perhaps the most complicated part of ortho-dontic diagnosis as it is rather subjective.12,13 Soft tissue preferences are more affected by the patient’s perception of beauty than a patient’s dental occlusion or skeletal relationship preference. Each patient’s perception of beauty can vary greatly by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and the person’s personal preference.12,13,14,15

Previous studies have been done to show improvement in the facial profile via functional appliances,11 but there still remains a lot of controversy over this topic in effectively obtaining ideal jaw relationships. Recently, Barroso, et al.,16 conducted a novel study analyzing the ability of orthodontists and laypeople to discriminate between mandibular stepwise advancements from a profile view. They concluded from their study that laypeople might not be able to discriminate 2 mm of mandibular advancement in evaluating facial-profile attractiveness as well as orthodontists.

Orthognathic surgery has helped significantly improve the soft tissue profile of many orthodontic patients.12,13,19,20,21 Dunlevy, et al.,17 reported that patients with smaller changes in mandibular position after mandibular advancement surgery were judged by laypersons to be less improved than those with larger changes from the profile view. Thus, if a large anteroposterior discrepancy is present, a surgical option may be a better treatment protocol to address profile esthetics than with just orthodontic treatment alone. Montini, et al.,18 suggested that when significant differences were present, significantly less improvement in the visual analog scale (VAS) score was perceived by laypersons than by their professional counterparts, indicating that the laypersons could not perceive the changes occurring or that they did not view an improvement in facial convexity as being important. This further reinforces why clinicians should take the patient’s preferences into account in their treatment planning, which could improve their understanding of the patient’s esthetic objectives.19,20,21 Previously, orthodontists exhibited a paternalistic view on the treatment planning process, making all the decisions for the patient that they believed to be in the best interest of the patient.22,23 In the new paradigm of evidence-based clinical practice (EBCP) a greater emphasis is now shifting toward patient autonomy, in which treatment “success” is possibly defined by patient satisfaction with the treatment outcome rather than time-honored, clinician-centered goals.24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31

Orthodontists and oral surgeons study profiles comprehensively and are trained to fixate on the areas of profile that are relevant to their respective profession: the lips, chin, nose, and dentoalveolar regions. In contrast, laypersons tend to be fixated on other aspects of the face, such as complexion, size and shape of the nose, chin shape, and hairstyle — all of which contribute to the perception of facial attractiveness.32,33 One study illustrated that even after profiles were “photographically warped” (a term that was used by the authors) to produce the same profile outline shape, there was still variability in attractiveness, denoting that other factors might impact facial esthetics other than the profile outline shape.6,34 Orthodontists pay specific attention to the esthetics of the face in profile when formulating a comprehensive orthodontic diagnosis and treatment plan.35,36 Interestingly, most laypeople cannot differentiate their own profile.33 This lack of attention to detail of the soft tissue profile highlights a distinction between how orthodontists and the general public rate facial profile esthetics.5,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 Orsini, et al., found in their study that laypeople evaluated prognathic profiles more negatively than retrognathic profiles whereas orthodontists preferred prognathic profiles to retrognathic profiles.44 However, Bonetti, et al.,45 demonstrated that laypersons seldom view a person’s facial profile unless it is viewed via diagnostic photographs. In other words, people tend to converse with each other and view one another’s facial attractiveness from a frontal and oblique perspective rather than side profile position. Although this study was well designed, it utilized a computer-imaging software to alter the patient’s profile instead of the patients’ actual natural profiles. Other studies have also reinforced using the oblique view of the face since people are generally observed by others at a slight angle in daily interaction,46,47 and this oblique view provides the best impression of an individual’s facial appearance.48 The three-quarter facial photographs have been reported to be reliable and valid in the assessment of facial attractiveness.49 Allowing patients to view their pretreatment facial photographs may reduce the discrepancy between patients’ perceived levels of facial attractiveness, thus making orthodontists’ and patients’ visual emphasis on dentofacial esthetics more similar to one another. In conclusion, self-perception is strongly based upon how individuals view themselves in the mirror, and it has been reported that frontal views of the face and smile seem to be their chief concern.50,51

The aim of this study was to determine if a large mandibular advancement (6 mm) or a small mandibular advancement (2 mm) changes esthetics ratings from a frontal view and three-quarter view perspective. Further, this study will characterize if there is any difference in the resultant esthetics of the male subjects’ versus female subjects’ mandibular advancement. This study will also compare the esthetic rating of orthodontists versus laypersons. This study will aid the practicing clinician in determining to what extent the advancement of the mandible changes facial esthetics from a frontal and three-quarter view.

Materials and methods

Frontal view and three-quarter view photographs of 12 Caucasian subjects: Six male and six female subjects, ages 10 to 16, prior to orthodontic treatment were collected and evaluated for participation in the study. All materials were collected after approval from the Seton Hill IRB committee. The subjects’ records were obtained from pretreatment records from orthodontic residents at a postgraduate orthodontic specialty program and at private practice clinics in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-area. The subjects had the following inclusion criteria:

A. At least ≥ 6 mm of overjet to facilitate mandibular stepwise advancements of 5 mm-6 mm from maximum intercuspation (MIP)

B. General facial symmetry, with slight deviation of the chin being acceptable (≤ 2 mm of chin deviation acceptable with no mentalis strain and no chin clefts)

C. Angle’s Class II Division 1 malocclusion dentally and skeletally with a retrognathic mandible

D. No occlusal cant

E.SN-MP ranging from 25° to 30°

Six laypersons rated each male or female subject recruited for average attractiveness on a 7-point Likert scale until one male and one female subject were rated as having the most average attractiveness (a rating of 3-4). The screening of patients ended once one male and one female patient of average attractiveness were identified and had met the inclusion criteria. The goal was to obtain one male subject and one female subject (two subjects total) who underwent stepwise mandibular advancements from centric relation to achieve a natural-looking face.

All analyses and photo uploads were done by Dolphin Imaging software (Dolphin Imaging & Management Solutions, Chatsworth, California). The resident or orthodontist who was overseeing the patient’s treatment traced and digitized the lateral cephalometric radiographs onto the Dolphin Imaging software (Dolphin Imaging & Management Solutions, Chatsworth, California). The overseeing resident or orthodontist also confirmed that the patient was skeletal Class II via the Sassouni cephalo-metric analysis. Upon selection of suitable candidates for the study, each subject was contacted by phone or email and informed of the purposes of the study. Informed consents were obtained from the subject for the study.

Photographs were obtained using an 18 megapixel digital camera and ring flash (Canon® EOS Rebel T3i DSLR camera and MR-14EX Macro Ring Lite, Canon, Tokyo, Japan) with adjustable 18 mm-55 mm lens. The settings for the camera were set for manual mode, ISO 100, aperture setting at f/8.0, and shutter speed at 1/160. The images were uploaded, scanned, and adjusted with regard to different brightness and contrast using specific imaging software (Dolphin Imaging & Management Solutions). J.L took the photos of the frontal facial profiles with the lens of the camera positioned perpendicular to the face in natural head position,52 while the three-quarter profiles were taken with the lens of the camera positioned approximately 45 degrees to the right of the facial midline. Patients focused on a specific target “X” marked on the wall with tape and had their heads adjusted until natural head position was achieved. These photos were taken at a distance of 1 foot away from the subject, with a lines marked on the floor for both the subject and experimenter to stand for consistency. The resident or orthodontist

overseeing the patient’s case evaluated the position where the photos are taken for consistency. A white light box was used as background to improve the quality of the images. Photographs were printed on 8.5″ x 11″ photographic paper, identified by printing the subject’s initials on the reverse side, and placed in a specific sequence generated by a random number generator (Figures 1 and 2).

A VAS has been widely utilized in different areas of dental research.53 In orthodontics, the VAS has been used as a measuring tool in studies about dentofacial esthetic assessment.54 This measurement tool has been used in assessing the facial esthetics perceptions by various groups of raters, including orthodontists and laypersons.5 It is a measurement instrument for subjective characteristics or attitudes between two endpoints on 50 mm or 100 mm continuums.55 Although the specifics of what makes one attractive or unattractive cannot be exactly determined, the rating of attractiveness is very reliable, and subjects were able to make a realistic appraisal of attractiveness.56,57 VAS was utilized in the study to help determine facial attractiveness scores of the female and male target persons.

Selection of target persons

Potential patients were presented to the orthodontic clinics and underwent a routine initial exam by an orthodontic resident or orthodontist. In addition to the routine exam forms for the initial exam, as well as full records, the resident or orthodontist conducting the exam checked off a form clearly stating the inclusion criteria for the study and, if the patient met the criteria, gave the form to the principal investigator (J.L). A list of patients that met the inclusion criteria was provided to the principal investigator. At the initial records appointment, J.L confirmed that the patient truly had a Class II Division 1 malocclusion with a retrognathic mandible via their lateral cephalogram by using the Sassouni analysis.58,59 To ensure patients were not posturing forward, J.L. had them touch their tongue to the roof of their mouth and slowly close their jaw to get them as close to centric relation as possible. Potential patients were also screened at private practice clinics located in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area.

Manipulation of target persons

Before obtaining the photo images, bilateral vertical marks were painted intraorally with indelible pencil on the buccal cusp tips of the upper first premolars with reference (A) mark on the occlusion in MIP. Using the reference (A) mark as a guide, four other marks were painted on the lower arch. The first one (reference mark No. 1), was coincident to reference mark (A) and two others marks: 2 mm (No. 2), and 6 mm (No. 3) distal to mark No.1. Using these marks, the subject was able to be positioned to be photographed in three different mandibular “positions” or mandibular stepwise advancements from MIP: The first was in MIP (marks [A] coincident with No. 1), and the others were stepwise mandible advancements of 2 mm (marks [A] coincident to No. 2), and 6 mm (marks [A] coincident to No. 3) (Figure 3). The initial mandibular position and other positions were guided using a 2.5 mm bite registration sheet wax (Part No. 42600, Almore International Inc., Beaverton, Oregon). The plate of wax was gently intercuspated while pictures were taken (Figure 4). To ensure accuracy, another resident or private practice orthodontists checked the mandibular position just before taking both pictures while the principal investigator (J.L.) took the pictures. Once all the photos were obtained for the subject, an alcohol swab was used to remove the marks from the patient’s dentition. The photographs had the target persons’ eyes blocked out prior to submission for publication to protect their identity and further minimize any possible psychological risk.60

Before obtaining the photo images, bilateral vertical marks were painted intraorally with indelible pencil on the buccal cusp tips of the upper first premolars with reference (A) mark on the occlusion in MIP. Using the reference (A) mark as a guide, four other marks were painted on the lower arch. The first one (reference mark No. 1), was coincident to reference mark (A) and two others marks: 2 mm (No. 2), and 6 mm (No. 3) distal to mark No.1. Using these marks, the subject was able to be positioned to be photographed in three different mandibular “positions” or mandibular stepwise advancements from MIP: The first was in MIP (marks [A] coincident with No. 1), and the others were stepwise mandible advancements of 2 mm (marks [A] coincident to No. 2), and 6 mm (marks [A] coincident to No. 3) (Figure 3). The initial mandibular position and other positions were guided using a 2.5 mm bite registration sheet wax (Part No. 42600, Almore International Inc., Beaverton, Oregon). The plate of wax was gently intercuspated while pictures were taken (Figure 4). To ensure accuracy, another resident or private practice orthodontists checked the mandibular position just before taking both pictures while the principal investigator (J.L.) took the pictures. Once all the photos were obtained for the subject, an alcohol swab was used to remove the marks from the patient’s dentition. The photographs had the target persons’ eyes blocked out prior to submission for publication to protect their identity and further minimize any possible psychological risk.60

Selection of raters

Two panels consisting of orthodontists and laypersons were assembled by the following criteria: a) The orthodontist group consisted of orthodontic faculty or practicing orthodontists who had at least 2 to 3 years of clinical practice experience and were drawn from only faculty at Seton Hill University Center for Orthodontics; and b) the layperson group were drawn from undergraduate students at Seton Hill University between the ages of 15 and 21.61 Informed consents were collected from raters participating in the study. The panelists were instructed to rate the six photographs for each male and female subject on a 100 mm VAS with “esthetically unpleasing” (0 mm) and “esthetically pleasing” (100 mm) as the two extremes for both the male and female subject groups, rating a total of 12 photos. One duplicate photo was added for each male and female subject set for a total of 14 photos to determine reliability. The photos were randomized with a random number generator. No time limit was imposed during the sessions. Laypersons and orthodontists rated the photographs in separate sessions with no principal investigators present.31 Panelists were not aware of the aims of the study to minimize bias or a Hawthorne effect. Written and visual instruction was given to the raters. Each rater scored each of the photos within the binder one time through.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis consisted of a 2x2x3x2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests whenever significant differences were found. It consisted of four factors: 1) view (Frontal or three-quarter), 2) mandibular position (0 mm, 2 mm, or 6 mm), 3) gender (male and female target person photos), and 4) judges (orthodontists or laypeople). For this study, there were 10 orthodontic raters and 152 layperson raters. The number of laypersons was substantially greater than the number of orthodontist raters.62,63,64 The analysis compared gender among laypersons to evaluate differences in facial attractiveness from a frontal or three-quarter view. All data with a P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM, Armonk, New York).

Results

Results

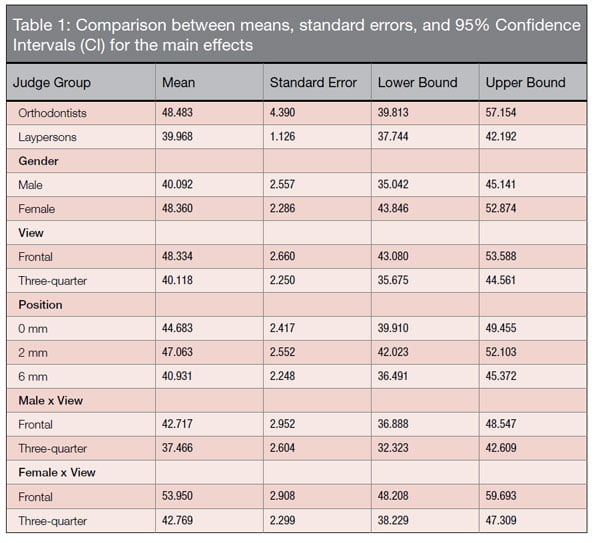

The results for the study are reported through Tables 1-3. Ten orthodontists and 152 laypersons were recruited to participate in the study. Gender was categorized as male or female, the views were categorized as frontal or three-quarter view, the position of the photo was categorized into 0 mm, 2 mm, and 6 mm advancements, and the judge groups were categorized into orthodontists and laypersons.

The study examined main effects and interaction effects: The main effects studied were gender, view, position of the photo and judge group, while the interaction effects explored how each of the main effects related to one another. Gender was highly statistically significant (F = 22.935) (P < 0.0001), with the female photo (mean = 48.360) receiving higher attractiveness scores to the male photo (mean = 40.092) among both orthodontists and laypersons (Table 1). When both target persons were recruited into the study, the female target person scored slightly higher average attractiveness scores (mean = 3.67) compared to the male target person (mean = 3.33), indicating that the female subject was slightly more attractive than the male before the study began.

The study examined main effects and interaction effects: The main effects studied were gender, view, position of the photo and judge group, while the interaction effects explored how each of the main effects related to one another. Gender was highly statistically significant (F = 22.935) (P < 0.0001), with the female photo (mean = 48.360) receiving higher attractiveness scores to the male photo (mean = 40.092) among both orthodontists and laypersons (Table 1). When both target persons were recruited into the study, the female target person scored slightly higher average attractiveness scores (mean = 3.67) compared to the male target person (mean = 3.33), indicating that the female subject was slightly more attractive than the male before the study began.

The main effects for view were highly significant (F = 18.078) (P < 0.0001), showing that both orthodontists and laypersons gave higher attractiveness ratings for the frontal view (mean = 48.334) when compared to the three-quarter view (mean = 40.118). There was no statistical significance regarding view and judge group rating the photos (Table 1).

The main effects for position were also found to be statistically significant (F = 9.55, p < 0.0004). Pair-wise comparison tests revealed that the 6 mm position was preferred less than either the 0 mm or 2 mm positions. There was no difference in preference between the 0 mm and 2 mm positions.

There were no significant differences between the two judge groups. Even though orthodontists gave higher ratings to the photos than the laypersons, the difference was not statistically significant (F = 3.53,

p = 0.062) (Table 2).

In regards to comparing interaction between the main effects, only two of the interaction effects (gender x view) and (gender x position), were statistically significant (P < 0.05). But these interaction effects were slightly underpowered (0.555 and 0.606) (F = 4.451 and F = 3.174). When tests for simple main effects were conducted for gender x view, no interaction effects could be detected. Tests for simple main effects for gender x position revealed no significant difference between 0 mm, 2 mm, and 6 mm advancement for the female photo, but for the male photo, 2 mm advancement was preferred to 0 mm, while 0 mm and 2 mm were preferred to 6 mm advancement (Table 3). All other comparisons of the other main effects were not statistically significant and had a low power value.

When evaluating intra-rater and inter-rater reliability, the reliability coefficient showed poor reliability with the original photos and the duplicate photos for both the male and female subject. The laypersons were more reliable than the orthodontists (0.775 vs. 0.493) for the male photo and (0.663 vs. 0484) for the female photo. Interjudge reliability among the 10 orthodontists was (0.736).

Discussion

In regards to views, the frontal view was preferred to the three-quarter view. It could be interpreted that all people, both orthodontists and laypersons, generally prefer facial attractiveness from the frontal view since people view each other mainly from the frontal perspective.45,65 Even though both subjects met the inclusion criteria and the soft tissue changes were more exaggerated for the male than the female, there may be other factors contributing to the facial attractiveness scores of the female, such as hairline, eyes, ear, nose, and other facial features.5,8 Although a small layperson group evaluated both patients for average facial attractiveness, it could be interpreted that for the main effects of gender, female subjects are generally viewed more attractive than male subjects. The female photo was preferred to the male for both the frontal and three-quarter view, and the frontal view was preferred to the three-quarter view for both the male and female photo. This finding contradicts previous studies, which shows that gender was not considered a factor influencing facial attractiveness.66,67 However, this finding could be attributed to the fact that the female target person was rated as more attractive than the male target person to begin with.

The low power observed in the study may be attributed to the fact that there were generally more laypersons available to participate in the study than orthodontists. Ideally, the power would be much higher if there were equal numbers of raters for both the orthodontists and laypersons group, but this is unrealistic because in the general population there are far fewer dentists than laypersons, with even fewer orthodontic specialists.68

The mandibular position of the photo did show a statistically significant difference among the three different positions at 6 mm. The facial attractiveness ratings at the 6 mm position were ranked the lowest among the three positions, indicating that a significantly protrusive position is least preferred by both judge groups. This finding differs from other studies where Caucasian cultures prefer slightly convex profiles,69,70 Korean cultures prefer slightly concave profiles,69 and Turkish cultures prefer orthognathic profiles.70

The present investigation shows that orthodontists tended to give higher ratings of attractiveness scores than laypersons when rating the photos. This may indicate that laypersons may be more critical of facial attractiveness than the orthodontists.71 This is in contrast to other studies, which found orthodontists were more critical than laypersons when rating facial attractiveness. This could be attributed to the fact that orthodontists are constantly evaluating the facial and smile esthetics, making them stricter in their evaluations.24,67,72,73 It also further suggests that beauty is very subjective and that each person’s view on facial attractiveness may vary greatly among each other.12,13,18,19

One interesting finding was shown when evaluating the interaction effects of the main effects. The facial attractiveness ratings for the female were almost rated the same for all the different positions in the frontal view than with the male group by the layperson judge group. It could be interpreted possibly that anteroposterior discrepancy for the female subject was not significant enough to show a discernible change.21

In regards to intrajudge reliability, both judge groups rated two photos twice during the experiment for the following photos: 1) the male photo at 2 mm from a three-quarter profile view and 2) the female photo at 0 mm from a frontal view. Orthodontists demonstrated that they were inconsistent with their ratings since their overall scores were lower for the duplicate photos than the laypersons. When determining interjudge reliability, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was utilized for the study.74 It was calculated using the scores of the 10 orthodontic judges for the 12 photos evaluated as the data set and was considered good because the ICC value was between 0.60 and 0.74. Interjudge reliability was not possible for the layperson group because there were far more laypersons than orthodontists for this to be determined.

From a clinical standpoint, the information gleaned from this pilot study can serve as preliminary data to establish esthetic preferences for both orthodontists and laypersons in both frontal and three-quarter views. Traditionally, orthodontists believed that treating to Angle’s Class I occlusion would yield the best treatment outcome,1,2,3 but this has shifted in recent years with more emphasis also given to soft tissue and smile esthetics.4,5,6 It is also imperative that patients are given autonomy for their treatment, as long as it causes no harm, and that their chief concerns are addressed as well in order to achieve the best possible treatment outcome.25,26,27,33,34,35 Since patients from various cultural backgrounds prefer different esthetic profiles, 69,70,73,74 it is also important to evaluate facial attractiveness from all the different aspects especially in the frontal and three-quarter view because laypersons tend to converse with each other from these perspectives.49,50,51,52 It may be interpreted that treating patients to an orthognathic profile may be an outdated treatment objective,48 and that treating to an orthognathic profile might not be a realistic and esthetic treatment outcome when assessing facial attractiveness from the frontal and three-quarter view. Given that the frontal view was preferred over the three-quarter view in the study, it may suggest that we should shift our attention to diagnosis and treatment planning for the frontal view more thoroughly in conjunction with the profile view because certain aspects of the profile are missing in the frontal view. Although this is an initial pilot study, there are some ways to improve the study design. When recruiting potential target persons for the study, the subjects should initially have a full-cusp Class II dental pattern in maximum intercuspation. From this position, the mandible could be advanced to a Class I canine position to evaluate the soft tissue profile of the subjects. This may ensure that both the male and female subjects would have consistent changes as the mandible is advanced into the various positions.

One limitation of the study was the male target person chosen for the study. It can be interpreted that the male subject was too prognathic at 6 mm and did not exhibit as much of a Class II relationship compared to the female subject. Another potential limitation to the study was that there was not equal number of orthodontists to laypersons. However, it is not realistic to get an equal number of orthodontists since there are fewer orthodontists in the general population.71 Another possible limitation was that all orthodontist raters were Caucasian raters. Although a majority of the layperson raters were Caucasian, the other ethnic raters (Asian, African-American, and Hispanic) could have skewed the results slightly. Therefore, stricter exclusion criteria may be of value. Finally, another possible limitation was the use of an 18 mm–55 mm lens instead of a 18 mm–105 mm lens because the potential for facial distortion exists, since the 18 mm–55 mm lens is not able to capture as sharp an image as the 18 mm–105 mm lens.

Conclusions

- There was a statistically significant difference for the following main effects: gender and view.

- The female photo was preferred to the male for both the frontal and three-quarter view

- The frontal view was preferred to the three-quarter view for both the male and female photo.

- There were two statistically significant differences among the interaction effects for both (gender x view) and (gender x position), but both were slightly underpowered.

Authors

Jeffrey H. Lee, DDS, MS, is a former resident at Seton Hill University Center for Orthodontics, Greensburg, Pennsylvania. and is currently practicing in the San Francisco Bay area.

Daniel Rinchuse, DMD, MS, MDS, PhD, is a Professor and Program Director, Seton Hill University Center for Orthodontics.

Thomas Zullo, PhD, is an Adjunct Professor of Biostatistics, Seton Hill University Center for Orthodontics, Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

Lauren Sigler Busch, DDS, MS, is in private practice in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and is also an adjunct professor at Seton Hill University Center for Orthodontics.

- Proffit WR, Fields HW Jr, Sarver DM. Contemporary Orthodontics. 5th ed., St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2013.

- De Smit A, Dermaut L. Soft-tissue profile preferences. Am J Orthod. 1984;86(1): 67-73.

- Ackerman JL, Proffit WR, Sarver DM. The emerging soft tissue paradigm in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Clin Orthod Res. 1999;2(2): 49-52.

- Tsang ST, McFadden LR, Wiltshire WA, Pershad N, Baker AB. Profile changes in orthodontic patients treated with mandibular advancement surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 135(1): 66-72.

- Maple JR, Vig KW, Beck FM, Larsen PE, Shanker S. A comparison of providers’ and consumers’ perceptions of facial-profile attractiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128(6): 690-696.

- Spyropoulos MN, Halazonetis DJ. Significance of the soft tissue profile on facial esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119(5): 464-471.

- Dongieux J, Sassouni V. The contribution of mandibular positioned variation to facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 1980;50(4): 334-339.

- Hodge TM, Boyd PT, Munyombwe T, Littlewood SJ. Orthodontists’ perceptions of the need for orthognathic surgery in patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusion based on extraoral examinations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142(1): 52-59.

- Wey MC, Bendeus M, Peng L, Hagg U, Rabie AB, Robinson W. Stepwise advancement versus maximum jumping with headgear activator. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29(3): 283-293.

- Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JA Jr. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II maloclussion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5): 599.e1-e12.

- Baccetti T, Franchi L, Stahl F. Comparison of 2 comprehensive Class II treatment protocols including the bonded Herbst and headgear appliances: a double-blind study of consecutively treated patients at puberty. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(6): 698.e1-10.

- McCollum T. TOMAC: an orthognathic treatment planning system. Part I soft tissue analysis. J Clin Orthod. 2001;35(6): 356-364.

- Jacobson A, Jacobson RL. Radiographic Cephalometry: From Basics to 3-D Imaging. 2nd ed. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2007.

- Câmara CA. Esthetics in Orthodontics: six horizontal smile lines. Dental Press J Orthod. 2010;15(1): 118-131.

- McLeod C, Fields HW, Hechter F, Wiltshire W, Rody W Jr, Christensen J. Esthetics and smile characteristics evaluated by laypersons. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(2): 198-205.

- Barroso MC, Silva NC, Quintão CC, Normando D. The ability of orthodontists and laypeople to discriminate mandibular stepwise advancements in a Class II retrognathic mandible. Prog Orthod. 2012; 13(2): 141-147.

- Dunlevy HA, White RP, Turvey TA. Professional and lay judgment of facial esthetic changes following orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1987;2(3): 151-158.

- Montini RW, McGorray SP, Wheeler TT, Dolce C. Perceptions of orthognathic surgery patient’s change in profile: a five-year follow-up. Angle Orthod. 2007;77(1): 5-11.

- Krishnan V, Daniel ST, Lazar D, Asok A. Characterization of posed smile by using visual analog scale, smile arc, buccal corridor measures, and modified smile index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(4): 515-523.

- Machado AW, McComb RW, Moon W, Gandini LG Jr. Influence of the vertical position of maxillary central incisors on the perception of smile esthetics among orthodontists and laypersons. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2013;25(6): 392-401.

- McKeta N, Rinchuse DJ, Close JM. Practitioner and patient perceptions of orthodontic treatment: Is the patient always right? J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(1): 40-50.

- Ackerman JL, Proffit WR. Communication in orthodontic treatment planning: bioethical and informed consent issues. Angle Orthod. 1995;65(4): 253-262.

- Sarver DM. Commentary: Practitioner and patient perceptions of orthodontic treatment: Is the patient always right? J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(1): 51–52. doi:10.1111 / j.1708-8240.2011.00456.

- Ismail AI, Bader JD; ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and Division of Science; Journal of the American Dental Association. Evidence-based dentistry in clinical practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(1):78-83.

- Ackerman M. Evidence-based orthodontics in the 21st century. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(2): 162-167.

- Turpin DL. Consensus builds for evidence-based methods. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004; 125:1-2.

- Keim RC. The editor’s corner: the power of the pyramid. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41(10): 587-588.

- American Dental Association Council on Ethics, Bylaws, and Judicial Affairs. 2010. Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Publications/Files/ADA_Code_of_Ethics_2016.pdf?la=en. (accessed October 29, 2016).

- Ackerman MB. Enhancement Orthodontics: Theory and Practice. 1st ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007.

- Phillips C. Patient-centered outcomes in surgical and orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod. 1999;5(4):223-230.

- Vig KW, Weyant R, O’Brien K, Bennett E. Developing outcome measures in orthodontics that reflect patient and provider values. Semin Orthod. 1999;5(2):85-95.

- Hockley A, Weinstein M, Borislow AJ, Braitman LE. Photos vs silhouettes for evaluation of African American profile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141(2):161-168.

- Cochrane SM, Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP. Perceptions of facial appearance by orthodontists and the general public. J Clin Orthod. 1997; 31: 164-8.

- Mantzikos T. Esthetic soft tissue profile preferences among Japanese population. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114(1):1-7.

- Soh J, Chew MT, Wong HB. A comparative assessment of the perception of Chinese facial profile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127(6):692-699.

- Siquiera DF, Sousa MV, Carvalho PE, do Valle-Corotti KM. The importance of the facial profile in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning: a patient report. World J Orthod. 2009;10(4):361-370.

- Soh J, Chew MT, Chan YH. Perceptions of dental esthetics of Asian orthodontists and laypersons. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(2):170-176.

- Foster EJ. Profile preferences among diversified groups. Angle Orthod. 1973;43:34-40.

- Isiksal E, Hazar S, Akyalcin S. Smile esthetics: perception and comparison of treated and untreated smiles. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(1):8-16.

- McKoy-White J, Evans CA, Viana G, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Facial profile preferences of black women before and after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(1):17-23.

- Gracco A, Cozzani M, D’Elia L, Manfrini M, Peverada C, Siciliani G. The smile buccal corridors: aesthetic value for dentists and laypersons. Prog Orthod. 2006;7(1):56-65.

- McCoy-White, Evans CA, Viana G, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Facial profile preferences of black women before and after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(1): 17-23.

- Coleman GG, Lindauer SJ, Tüfekçi E, Shroff B, Best AM. Influence of chin prominence on esthetic lip profile preferences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(1):36-42.

- Orsini MG, Huang GJ, Kiyak HA, Ramsay DS, Bollen AM, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Methods to evaluate profile preferences for the anteroposterior position of the mandible. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(3):283-291.

- Bonetti GA, Alberti A, Sartini C, Parenti SI. Patients’ self-perception of dentofacial attractiveness before and after exposure to facial photographs. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(3):517-524.

- Peerlings RH, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Hoeksma JB. A photographic scale to measure facial aesthetics. Eur J Orthod. 1995;17(2):101-109.

- Sarver DM. The face as the determinant of the treatment choice. In: McNamara JA, Kely KA, Ferrara eds. Frontiers of dental and facial esthetics. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development; University of Michigan; 2001.

- Van der Linden FPGM, Boersma H. Diagnostic aids. In: Van der Linder FPGM, Boersma H, editors. Diagnosis and treatment planning in dentofacial orthopedics. London: Quintessence; 1987.

- Howells DJ, Shaw WC. The validity and reliability of ratings of dental and facial attractiveness for epidemiologic use. Am J Orthod. 1985;88(5):402-408.

- Tüfekçi E, Jahangiri A, Lindauer SJ. Perception of profile among laypeople, dental students and orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2008;78(6):983-987.

- Shafiee R, Korn EL, Pearson H, Boyd RL, Baumrind S. Evaluation of facial attractiveness from end-of-treatment facial photographs. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(4):500-508.

- Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36(4):221-236.

- Aitken RC. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62(10): 17-21.

- Burstone CJ. Lip posture and its significance in treatment planning. Am J Orthod. 1967;53(4):262-284.

- Reips U-D, Funke F. Interval-level measurement with visual analogue scales in Internet-based research: VAS Generator. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):699-704.

- Berscheid E. An overview of the psychological effects of physical attractiveness. In: Lucker GW, Ribbens KA, McNamara JA, eds. Psychological aspects of facial form. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development; University of Michigan; 1980.

- Graber L. Psychological Considerations of Orthodontic Treatment. In: Lucker GW, Ribbens KA, McNamara JA, eds. Psychological aspects of facial form. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development; University of Michigan; 1980.

- Sassouni V. A classification of skeletal facial types. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(2):109-123.

- Sassouni V. A roentgenographic cephalometric analysis of cephalofacial-dental relationships. Am J Orthod. 1995;41:735-764.

- Maurya R, Gupta A, Garg J, Shukla C. Evaluate the influence of panel composition on facial attractiveness. J Orthod Res. 2015;3(1):25-29.

- Kerr WJS, O’Donnell JM. Panel perception of facial attractiveness. Br J Orthod. 1990;17(4):299-304.

- Williams RP, Rinchuse DJ, Zullo TG. Perceptions of midline deviations among different facial types. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(2):249-255.

- Kokich VO, Kokich VG, Kiyak HA. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(2):141-51.

- Yin L, Jiang M, Chen W, Smales RJ, Wang Q, Tang L. Differences in facial profile and dental esthetic perceptions between young adults and orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(6):750-756.

- Proffit WR, Phillips C, Douvartzidis N. A comparison of outcomes of orthodontic and surgical orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusion in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992; 101:556-565.

- Mejia-Maidl M, Evans CA, Viana G, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Preferences for facial profiles between Mexican Americans and Caucasians. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:953-958.

- Chong HT, Thea KW, Descallar J, Chen Y, Dalci O, Wong R, Darendeliler MA. Comparison of White and Chinese perception of esthetic Chinese lip position. Angle Orthod. 2014; 84: 246-253.

- American Dental Education Association: Dentists and Demographics. 2008. Available at: www.adea.org/deansbriefing/documents/finalreviseddeans/dentistsdemographics.pdf (accessed October 29, 2016).

- Hwang HS, Kim WS, McNamara JA Jr. Ethnic differences in the soft tissue profile of Korean and European-American adults with normal occlusions and well-balanced faces. Angle Orthod. 2002;72(1):72-80.

- Türkkahraman H, Gökalp H. Facial profile preferences among various layers of Turkish population. Angle Orthod. 2004;74(5):640-647.

- Zange SE, Ramos AL, Cuoghi OA, de Mendonça MR, Suguino R. Perceptions of laypersons and orthodontists regarding the buccal corridor in long- and short-face individuals. Angle Orthod. 2011; 81(1): 86-90.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11(6):311-324.

- Machado RM, Assad Duarte ME, Jardim da Motta AF, Mucha JN, Motta AT. Variations between maxillary central and lateral incisal edges and smile attractiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;150(3):425-435.

- Cicchetti, DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284–290. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284.

References

- Proffit WR, Fields HW Jr, Sarver DM. Contemporary Orthodontics. 5th ed., St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2013.

- De Smit A, Dermaut L. Soft-tissue profile preferences. Am J Orthod. 1984;86(1): 67-73.

- Ackerman JL, Proffit WR, Sarver DM. The emerging soft tissue paradigm in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Clin Orthod Res. 1999;2(2): 49-52.

- Tsang ST, McFadden LR, Wiltshire WA, Pershad N, Baker AB. Profile changes in orthodontic patients treated with mandibular advancement surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 135(1): 66-72.

- Maple JR, Vig KW, Beck FM, Larsen PE, Shanker S. A comparison of providers’ and consumers’ perceptions of facial-profile attractiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128(6): 690-696.

- Spyropoulos MN, Halazonetis DJ. Significance of the soft tissue profile on facial esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119(5): 464-471.

- Dongieux J, Sassouni V. The contribution of mandibular positioned variation to facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 1980;50(4): 334-339.

- Hodge TM, Boyd PT, Munyombwe T, Littlewood SJ. Orthodontists’ perceptions of the need for orthognathic surgery in patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusion based on extraoral examinations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142(1): 52-59.

- Wey MC, Bendeus M, Peng L, Hagg U, Rabie AB, Robinson W. Stepwise advancement versus maximum jumping with headgear activator. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29(3): 283-293.

- Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JA Jr. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II maloclussion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5): 599.e1-e12.

- Baccetti T, Franchi L, Stahl F. Comparison of 2 comprehensive Class II treatment protocols including the bonded Herbst and headgear appliances: a double-blind study of consecutively treated patients at puberty. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(6): 698.e1-10.

- McCollum T. TOMAC: an orthognathic treatment planning system. Part I soft tissue analysis. J Clin Orthod. 2001;35(6): 356-364.

- Jacobson A, Jacobson RL. Radiographic Cephalometry: From Basics to 3-D Imaging. 2nd ed. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2007.

- Câmara CA. Esthetics in Orthodontics: six horizontal smile lines. Dental Press J Orthod. 2010;15(1): 118-131.

- McLeod C, Fields HW, Hechter F, Wiltshire W, Rody W Jr, Christensen J. Esthetics and smile characteristics evaluated by laypersons. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(2): 198-205.

- Barroso MC, Silva NC, Quintão CC, Normando D. The ability of orthodontists and laypeople to discriminate mandibular stepwise advancements in a Class II retrognathic mandible. Prog Orthod. 2012; 13(2): 141-147.

- Dunlevy HA, White RP, Turvey TA. Professional and lay judgment of facial esthetic changes following orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1987;2(3): 151-158.

- Montini RW, McGorray SP, Wheeler TT, Dolce C. Perceptions of orthognathic surgery patient’s change in profile: a five-year follow-up. Angle Orthod. 2007;77(1): 5-11.

- Krishnan V, Daniel ST, Lazar D, Asok A. Characterization of posed smile by using visual analog scale, smile arc, buccal corridor measures, and modified smile index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(4): 515-523.

- Machado AW, McComb RW, Moon W, Gandini LG Jr. Influence of the vertical position of maxillary central incisors on the perception of smile esthetics among orthodontists and laypersons. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2013;25(6): 392-401.

- McKeta N, Rinchuse DJ, Close JM. Practitioner and patient perceptions of orthodontic treatment: Is the patient always right? J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(1): 40-50.

- Ackerman JL, Proffit WR. Communication in orthodontic treatment planning: bioethical and informed consent issues. Angle Orthod. 1995;65(4): 253-262.

- Sarver DM. Commentary: Practitioner and patient perceptions of orthodontic treatment: Is the patient always right? J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(1): 51–52. doi:10.1111 / j.1708-8240.2011.00456.

- Ismail AI, Bader JD; ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and Division of Science; Journal of the American Dental Association. Evidence-based dentistry in clinical practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(1):78-83.

- Ackerman M. Evidence-based orthodontics in the 21st century. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(2): 162-167.

- Turpin DL. Consensus builds for evidence-based methods. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004; 125:1-2.

- Keim RC. The editor’s corner: the power of the pyramid. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41(10): 587-588.

- American Dental Association Council on Ethics, Bylaws, and Judicial Affairs. 2010. Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Publications/Files/ADA_Code_of_Ethics_2016.pdf?la=en. (accessed October 29, 2016).

- Ackerman MB. Enhancement Orthodontics: Theory and Practice. 1st ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007.

- Phillips C. Patient-centered outcomes in surgical and orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod. 1999;5(4):223-230.

- Vig KW, Weyant R, O’Brien K, Bennett E. Developing outcome measures in orthodontics that reflect patient and provider values. Semin Orthod. 1999;5(2):85-95.

- Hockley A, Weinstein M, Borislow AJ, Braitman LE. Photos vs silhouettes for evaluation of African American profile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141(2):161-168.

- Cochrane SM, Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP. Perceptions of facial appearance by orthodontists and the general public. J Clin Orthod. 1997; 31: 164-8.

- Mantzikos T. Esthetic soft tissue profile preferences among Japanese population. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114(1):1-7.

- Soh J, Chew MT, Wong HB. A comparative assessment of the perception of Chinese facial profile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127(6):692-699.

- Siquiera DF, Sousa MV, Carvalho PE, do Valle-Corotti KM. The importance of the facial profile in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning: a patient report. World J Orthod. 2009;10(4):361-370.

- Soh J, Chew MT, Chan YH. Perceptions of dental esthetics of Asian orthodontists and laypersons. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(2):170-176.

- Foster EJ. Profile preferences among diversified groups. Angle Orthod. 1973;43:34-40.

- Isiksal E, Hazar S, Akyalcin S. Smile esthetics: perception and comparison of treated and untreated smiles. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(1):8-16.

- McKoy-White J, Evans CA, Viana G, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Facial profile preferences of black women before and after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(1):17-23.

- Gracco A, Cozzani M, D’Elia L, Manfrini M, Peverada C, Siciliani G. The smile buccal corridors: aesthetic value for dentists and laypersons. Prog Orthod. 2006;7(1):56-65.

- McCoy-White, Evans CA, Viana G, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Facial profile preferences of black women before and after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(1): 17-23.

- Coleman GG, Lindauer SJ, Tüfekçi E, Shroff B, Best AM. Influence of chin prominence on esthetic lip profile preferences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(1):36-42.

- Orsini MG, Huang GJ, Kiyak HA, Ramsay DS, Bollen AM, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Methods to evaluate profile preferences for the anteroposterior position of the mandible. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(3):283-291.

- Bonetti GA, Alberti A, Sartini C, Parenti SI. Patients’ self-perception of dentofacial attractiveness before and after exposure to facial photographs. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(3):517-524.

- Peerlings RH, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Hoeksma JB. A photographic scale to measure facial aesthetics. Eur J Orthod. 1995;17(2):101-109.

- Sarver DM. The face as the determinant of the treatment choice. In: McNamara JA, Kely KA, Ferrara eds. Frontiers of dental and facial esthetics. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development; University of Michigan; 2001.

- Van der Linden FPGM, Boersma H. Diagnostic aids. In: Van der Linder FPGM, Boersma H, editors. Diagnosis and treatment planning in dentofacial orthopedics. London: Quintessence; 1987.

- Howells DJ, Shaw WC. The validity and reliability of ratings of dental and facial attractiveness for epidemiologic use. Am J Orthod. 1985;88(5):402-408.

- Tüfekçi E, Jahangiri A, Lindauer SJ. Perception of profile among laypeople, dental students and orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2008;78(6):983-987.

- Shafiee R, Korn EL, Pearson H, Boyd RL, Baumrind S. Evaluation of facial attractiveness from end-of-treatment facial photographs. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(4):500-508.

- Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36(4):221-236.

- Aitken RC. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62(10): 17-21.

- Burstone CJ. Lip posture and its significance in treatment planning. Am J Orthod. 1967;53(4):262-284.

- Reips U-D, Funke F. Interval-level measurement with visual analogue scales in Internet-based research: VAS Generator. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):699-704.

- Berscheid E. An overview of the psychological effects of physical attractiveness. In: Lucker GW, Ribbens KA, McNamara JA, eds. Psychological aspects of facial form. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development; University of Michigan; 1980.

- Graber L. Psychological Considerations of Orthodontic Treatment. In: Lucker GW, Ribbens KA, McNamara JA, eds. Psychological aspects of facial form. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development; University of Michigan; 1980.

- Sassouni V. A classification of skeletal facial types. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(2):109-123.

- Sassouni V. A roentgenographic cephalometric analysis of cephalofacial-dental relationships. Am J Orthod. 1995;41:735-764.

- Maurya R, Gupta A, Garg J, Shukla C. Evaluate the influence of panel composition on facial attractiveness. J Orthod Res. 2015;3(1):25-29.

- Kerr WJS, O’Donnell JM. Panel perception of facial attractiveness. Br J Orthod. 1990;17(4):299-304.

- Williams RP, Rinchuse DJ, Zullo TG. Perceptions of midline deviations among different facial types. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(2):249-255.

- Kokich VO, Kokich VG, Kiyak HA. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(2):141-51.

- Yin L, Jiang M, Chen W, Smales RJ, Wang Q, Tang L. Differences in facial profile and dental esthetic perceptions between young adults and orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(6):750-756.

- Proffit WR, Phillips C, Douvartzidis N. A comparison of outcomes of orthodontic and surgical orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusion in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992; 101:556-565.

- Mejia-Maidl M, Evans CA, Viana G, Anderson NK, Giddon DB. Preferences for facial profiles between Mexican Americans and Caucasians. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:953-958.

- Chong HT, Thea KW, Descallar J, Chen Y, Dalci O, Wong R, Darendeliler MA. Comparison of White and Chinese perception of esthetic Chinese lip position. Angle Orthod. 2014; 84: 246-253.

- American Dental Education Association: Dentists and Demographics. 2008. Available at: www.adea.org/deansbriefing/documents/finalreviseddeans/dentistsdemographics.pdf (accessed October 29, 2016).

- Hwang HS, Kim WS, McNamara JA Jr. Ethnic differences in the soft tissue profile of Korean and European-American adults with normal occlusions and well-balanced faces. Angle Orthod. 2002;72(1):72-80.

- Türkkahraman H, Gökalp H. Facial profile preferences among various layers of Turkish population. Angle Orthod. 2004;74(5):640-647.

- Zange SE, Ramos AL, Cuoghi OA, de Mendonça MR, Suguino R. Perceptions of laypersons and orthodontists regarding the buccal corridor in long- and short-face individuals. Angle Orthod. 2011; 81(1): 86-90.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11(6):311-324.

- Machado RM, Assad Duarte ME, Jardim da Motta AF, Mucha JN, Motta AT. Variations between maxillary central and lateral incisal edges and smile attractiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;150(3):425-435.

- Cicchetti, DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284–290. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores