CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

The purpose of this article is to review the impact intraoral scanning has had on the orthodontic profession, the evolution of the technology, and how its use affects clinicians, staff, and patients.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions with this quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize intraoral scanners’ effects on practice workflow.

- Realize intraoral scanners’ role in practice/lab relationships.

- Recognize intraoral scanners’ impact on fit of final appliances.

- Acknowledge intraoral scanners’ impact on patient comfort.

- Compare the true cost of traditional impressions versus digital impressions.

- Identify intraoral scanners’ impact on hygiene and patient safety

Dr. Robert Waugh discusses the many ways that intraoral scanners increase efficiency

Introduction

Computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) was first used in dentistry in the late 1970s/early 1980s in Europe. However, the sheer size of the equipment confined the technology to only the most advanced laboratories. In the early 2000s, developments in miniaturization made handheld scanners a reality for

dental practices.

As CAD/CAM technology was refined over the decade, new software algorithms were introduced to meet the unique needs of the orthodontic profession. According to an informal survey conducted the by the Journal of Clinical Orthodontics, 62% of respondents indicated they now use an intraoral scanner.1 Considering the rapid pace of technological advances in the digital space, it is worthwhile to consider the effects intraoral scanners have had and will continue to have on orthodontics. Not only that, considering the market position practices are in to attract patients, intraoral scanners are also unique in the role they play in patient satisfaction and retention.

Intraoral scanners’ effects on practice workflow

Studies show digital impressions are beneficial in creating a more efficient workflow.2 Although it varies based on examination needs, capturing a digital scan (versus taking a traditional impression) generates timesavings due to the speed that scanners allow. As Figure 1 illustrates, however, actual timesavings come from eliminating the additional steps associated with preparing for, working with, and shipping traditional impressions/models to the lab. It’s also important to note that the more steps there are in any process, the more opportunities exist for the introduction of errors.

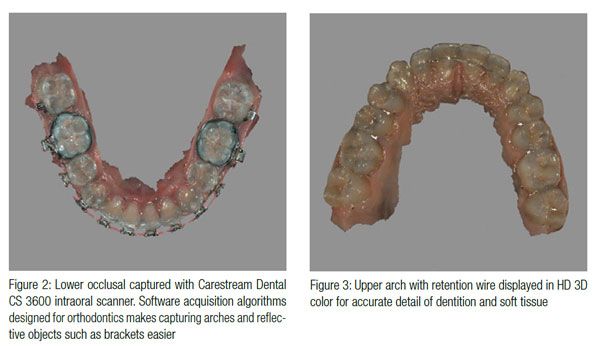

Recent advancements in software have tailored scanners to further fit orthodontists’ needs. For example, algorithms are optimized for fast dual-arch acquisition, facilitating an uninterrupted user experience in the orthodontic office. Integration with other imaging equipment and/or practice management software enables clinicians to quickly access the information they need with minimal clicks, further improving the treatment workflow.

Recent advancements in software have tailored scanners to further fit orthodontists’ needs. For example, algorithms are optimized for fast dual-arch acquisition, facilitating an uninterrupted user experience in the orthodontic office. Integration with other imaging equipment and/or practice management software enables clinicians to quickly access the information they need with minimal clicks, further improving the treatment workflow.

An improved workflow results in a process that is seamless from the moment the initial intraoral scan is taken. In most cases, it significantly decreases the total time required from impression to appliance delivery, saving chair time for clinicians and reducing disruptions to daily routines for patients.

An improved workflow results in a process that is seamless from the moment the initial intraoral scan is taken. In most cases, it significantly decreases the total time required from impression to appliance delivery, saving chair time for clinicians and reducing disruptions to daily routines for patients.

Intraoral scanners’ role in practice/lab relationships

Intraoral scanners’ role in practice/lab relationships

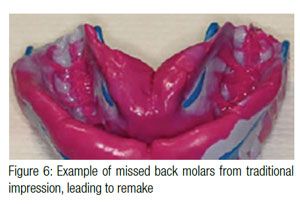

From the lab’s perspective, the impression-taking skills of clients can present a significant challenge. As many as 25% of the traditional impressions arriving at the lab are inadequate, due to a failure to follow guidelines and a lack of evaluating impressions before sending them to the lab.3 With intraoral scanners, it is possible to immediately send the digital impression to the lab for review. If there is an issue with the impression, the practice can rescan the patient while he/she is still in the chair. Once the lab receives the digital files from the intraoral scan, it can immediately communicate unmet needs to the office. If there is a question about the prescription or appliance, there is no lag time from shipping, which ultimately creates delays in fabrication.

The ability to communicate easily with third parties such as labs also facilitates the treatment-planning process. The file format accepted (either .STL or .PLY) varies from lab to lab. As a result, a scanner’s output should be in an open file format so that clinicians are not limited to only labs that accept a certain type of file. Within minutes of scanning, the lab receives these files and can open them in the design software of its choice. A phone call or remote viewing call from the lab to the orthodontist enables both parties to work together, even before the patient has left the appointment.

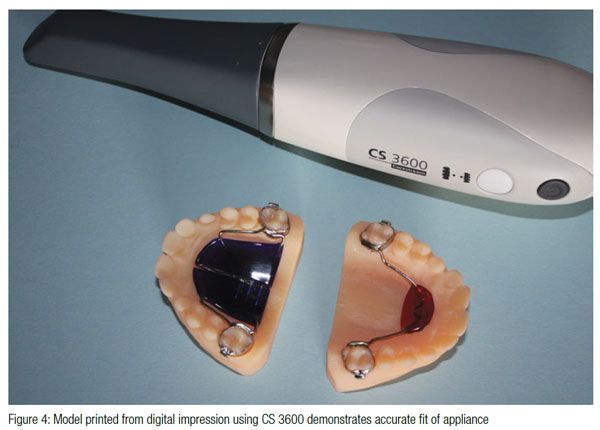

Intraoral scanners’ impact on fit of final appliances

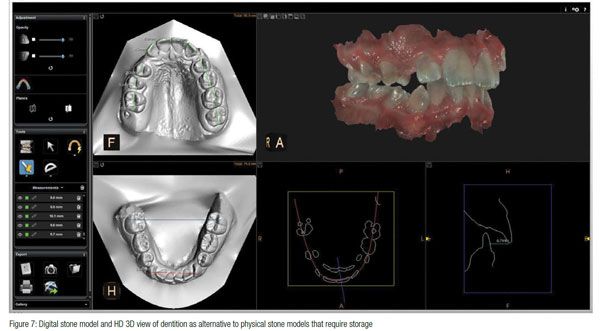

Digital scanners are generally acknowledged to be more accurate than traditional impressions,4 as they provide a level of detail of the dentition and soft tissue not previously available to oral health professionals. Additionally, orthodontists are at an advantage, as scans needed to fabricate appliances do not require nearly as much data as a scan meant to fabricate a crown or bridge (marked margin lines, interproximal and sub-gingival scans, etc.). Digital impressions lead to distortion-free models that some doctors feel result in appliances that fit more predictably than those fabricated using conventional methods. Better fitting appliances also result in higher quality treatment outcomes.

Intraoral scanners’ learning curve

Users take time to grow comfortable with any new technology, and the learning curve with digital scanners can vary from user to user. For experienced scanner operators, the need to rescan is minimal. However, sometimes scanners feature an auto-locate function that detects and corrects defects in the data set, which allows users to rescan an area to fill in missing information without starting over while the patient is still in the chair. This can help new scanner users gain confidence and hone their skill.

Beyond becoming familiar with the best technique for scanning for creating digital impressions, users must also change their mindset when analyzing models. Without a stone model to turn in their hands, physically probe, or bring close to the eye for examination, the switch to digital may be jarring. Adapting to software and manipulating models on a screen also takes adjustment. There are many benefits to introducing a digital scanner into an orthodontic workflow, but it’s recommended that practices allow extra time for the first three to five cases involving a scanner so that both the practice and lab can become familiar with the new workflow.

Intraoral scanners’ impact on patient comfort

Intraoral scanning eliminates the risk of patients gagging, an advantage for all parties involved. When the clinician performs a scan, if transient brushes with sensitive tissues occur, the clinician can simply move on and return in a more careful manner, recapturing that area after the patient has felt the accomplishment of the now nearly complete scan. The experience is more pleasant for both the patient and the clinician than with traditional impression methods.

Also, intraoral scanner tips typically come in two sizes to accommodate mouths of all sizes. These tips are ideal for anterior and occlusal surface scanning or for pediatric and adult scanning. If the scanner features a side-oriented tip, the clinician gains flexible choices in satisfying different clinical needs and user preferences. The side-oriented tip is designed to make it easier to obtain buccal surface scans, and the tip height is generally shorter than the standard tips. Side-oriented tips also enable greater access to the molars.

Intraoral scanners’ impact on practice ROI

When comparing the true cost of traditional impressions versus digital impressions, there are several factors to consider. First, intraoral scanners eliminate the cost of ordering consumables such as trays, alginate, etc., which, depending on practice size, can cost $1,500-$2,000 a month. Beyond the obvious cost-savings on materials, consider the cost of treatment if the practice needs to remake an impression or appliance. Assuming the lab doesn’t charge for a remake — which involves additional fees — if an assistant remakes a PVS impression, the cost in time and expense is actually threefold. First, the impression is unusable, resulting in the loss of both time and money. Second, the remake adds time and expense, in addition to wasting materials. Third, an assistant is not available for a new patient and/or procedure while attending to the remake.

When comparing the true cost of traditional impressions versus digital impressions, there are several factors to consider. First, intraoral scanners eliminate the cost of ordering consumables such as trays, alginate, etc., which, depending on practice size, can cost $1,500-$2,000 a month. Beyond the obvious cost-savings on materials, consider the cost of treatment if the practice needs to remake an impression or appliance. Assuming the lab doesn’t charge for a remake — which involves additional fees — if an assistant remakes a PVS impression, the cost in time and expense is actually threefold. First, the impression is unusable, resulting in the loss of both time and money. Second, the remake adds time and expense, in addition to wasting materials. Third, an assistant is not available for a new patient and/or procedure while attending to the remake.

Traditional stone models also put orthodontic practices in a unique position. While impressions may be safely destroyed, practices are obligated to store the stone models they create for a certain number of years past the patient’s age of majority. To calculate the actual cost of storing stone models, clinicians should consider cataloging time and space requirements. The effort required to categorize models, box them up, and move them to the designated storage area is typically not an efficient use of staff time. If the office is in a high-rent district where space is priced at a premium, storage can be very cost prohibitive. Instead, intraoral scanners can be used to digitize existing stone models.

Intraoral scanners’ impact on hygiene and patient safety

Asepsis is a critical concern for orthodontists, and maintaining an aseptic field of treatment is always a top-of-mind issue. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend that heat-tolerant semi-critical items in dentistry (items that come into contact with mucous membranes) be sterilized using heat. If heat sensitive, dental healthcare practitioners should replace semi-critical items with a heat-tolerant or disposable alternative.5

This recommendation underscores the need for the disinfecting practices of the intraoral scanner to include heat sterilization. Scanner tips should be autoclavable to promote optimal sterilization for infection control.

Intraoral scanners’ impact on patient education and case acceptance

Intraoral scanners’ impact on patient education and case acceptance

During pre-exam office tours, seeing an intraoral scanner in action can convey technological competence on behalf of the practice to the patient. When parents observe the image acquisition process and the resulting images — as well as how calm and cooperative their children are — they may become advocates for the state-of-the-art technology and the practice that uses it.

Also, images produced by the intraoral scanner also help patients and parents quickly comprehend the treatment plan. A digital model is presentation-ready as soon as scanning is complete. Thanks to the educational aspect of the model and a better understanding of their clinical situation, patients may feel more confident about the clinician’s approach. In addition, the same digital scan used for case presentation can be used to create an appliance if one is needed. With the traditional method, typically the patient is sent home so that the office can create the stone models, and a follow-up appointment is scheduled to review the model at a later date. These extra steps are eliminated with digital impressions as a model can be reviewed immediately after it is captured with the digital intra-oral scanner.

Conclusion

Intraoral scanners are having a tremendous impact on the practice of orthodontics. From fewer appointments to quicker turnaround times at the lab to improved outcomes and happier patients, intraoral scanning and digital models are setting the stage for greater efficiencies across the board. The simplicity of the scan-to-lab process — with a faster fabrication process, no remakes or substandard pour-ups, no need to package models in boxes, and no potential damage or loss in transit — is transformational to the field of orthodontics. Clinicians who adopt this technology are likely to discontinue the use of traditional impression material in their practices altogether.

References

- Sinclair, PM. The Readers’ Corner. J Clin Orthod. 2016;L(10):635-636.

- Patzelt SB, Lamprinos C, Stampf S, Att W. The time efficiency of intraoral scanners: an in vitro comparative study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(6):542-551.

- Marsico M. Some things never change: inadequate impressions still labs’ biggest client headache. LMT Communications Inc. https://lmtmag.com/topics/digital_impressions?view=articles. Accessed Mar 26, 2015.

- Hack GD, Patzelt SB. Evaluation of the accuracy of six intraoral scanning devices: an in-vitro. ADA Professional Product Review. 2015;10(4):1-5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Oral Health; 2016.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Robert Waugh, DMD, MS, has practiced orthodontics full time in Athens, Georgia, since 1989 and is also an Assistant Professor at Georgia Regents (USA) College of Dental Medicine’s Orthodontic Residency Program. Dr. Waugh’s interests include using new technologies that help deliver better care for his patients. In 2008, he merged three offices into one facility of 24 chairs that allows him to deliver care using a wide variety of modalities in hygiene, patient scheduling, treatment delivery, and more. Dr. Waugh graduated from GRU College of Medicine in 1987 with both a DMD and a master’s in Oral Biology and was elected to Omicron Kappa Upsilon (OKU). He earned his orthodontic certification and a second master’s degree at Baylor University in 1989. In 2000, he was board-certified by the American Board of Orthodontics. Dr. Waugh has served as President of the Georgia Association of Orthodontists and is a member of the International Colleges of Dentists.

Robert Waugh, DMD, MS, has practiced orthodontics full time in Athens, Georgia, since 1989 and is also an Assistant Professor at Georgia Regents (USA) College of Dental Medicine’s Orthodontic Residency Program. Dr. Waugh’s interests include using new technologies that help deliver better care for his patients. In 2008, he merged three offices into one facility of 24 chairs that allows him to deliver care using a wide variety of modalities in hygiene, patient scheduling, treatment delivery, and more. Dr. Waugh graduated from GRU College of Medicine in 1987 with both a DMD and a master’s in Oral Biology and was elected to Omicron Kappa Upsilon (OKU). He earned his orthodontic certification and a second master’s degree at Baylor University in 1989. In 2000, he was board-certified by the American Board of Orthodontics. Dr. Waugh has served as President of the Georgia Association of Orthodontists and is a member of the International Colleges of Dentists.