CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to discuss the benefits of smile bleaching during orthodontic treatment.

Expected outcomes

Orthodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize how motivation and compliance can interfere with the tooth- whitening process in non-adults.

- Recognize possible benefits of carbamide peroxide (CP) and hydrogen peroxide (HP) in the tooth-whitening

- Realize the benefits of prefilled, disposable trays and strips for tooth whitening.

- Identify some dentist-prescribed and -supervised products that allow the clinician to remain in control of the tooth-whitening process.

- Recognize some drawbacks to using some OTC products.

- Observe a case of tooth whitening during orthodontic treatment on a non-adult patient.

Drs. Jaimeé Morgan and Stan Presley discuss how appealing to patients’ desires for esthetic enhancement during orthodontic treatment can have other positive effects

Orthodontic patients are often overlooked when it comes to addressing their needs for whiter teeth. These patients are usually forced to wait until the end of treatment when the brackets are removed before tooth bleaching is even mentioned. Their arches may be beautifully rounded and teeth completely straightened, but oftentimes the discoloration or stains on the teeth distract from what should be a perfect smile. One group of orthodontic patients falls into this category; the other falls into a category of needing extra help in improving their oral hygiene. Both of these groups of patients can be addressed with the use of hydrogen peroxide (HP) and carbamide peroxide (CP) bleaching agents during their orthodontic treatment.

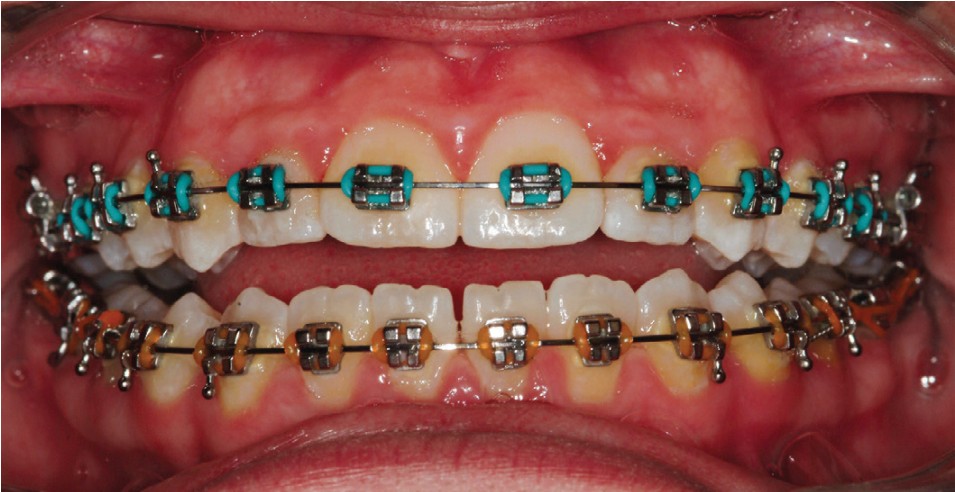

Patients going through orthodontic treatment seem to face real challenges when it comes to maintaining healthy gingival tissue and dentition. Plaque buildup, inflamed soft tissue, and bleeding can make even a simple retie appointment difficult (Figure 1). Then there are the long-term adverse effects, which include decalcification and decay around brackets (Figure 2). Preadolescent- and adolescent-aged patients make up about 80% of orthodontic treatment although adults seeking treatment is on the rise. Research has shown the emotional developmental stage of the non-adult group brings additional challenges — i.e., they can be influenced by peer pressure, reject authority, and believe that they are exempt from compromised health because of their uniqueness.

Sending patients home with a detailed home care instruction list and the armamentarium to accomplish these daily tasks include disclosing tablets, mechanical and manual toothbrushes, oral irrigating devices, mouth rinses, fluoride rinses, and floss. Even with all these excellent tools and instructions, it still comes down to motivation of and compliance by the patient. Considering patients generally have conventional in-office care only twice per year, the long-term benefits are not truly significant. The prevalence of white spot lesions (WSLs) remains at 61% when removing orthodontic appliances even with in-office efforts of prophylaxis and prevention., Therefore, home care with parental involvement must be emphasized.

With the introduction of fluoride varnishes, fluoride-releasing band and bracket adhesives, fluoride-releasing bonding agents, and antimicrobial orthodontic hardware, there have been decreases of WSLs as long as the varnishes are reapplied on a regular basis, and the fluoride in the fluoride-releasing materials is recharged. Recently introduced selenium-releasing bonding agents show promise although there has not been an abundance of studies comparing it with fluoride.3 Even with these clinically integrated products, the most effective course of action still remains the age-old approach of attacking the problem at its source — hence a combination of repeated home care instruction, frequent prophylaxis, and in-office and home-delivered topical fluoride. At this time, the patient is not released from participation in this effort.

Although CP and HP are excellent in decreasing plaque, inflammation, decalcification, and the incidence of decay, they are often overlooked.5,6,7,8,9,10 This omission is probably due to the common misconception that these materials must use custom trays. And where fixed orthodontic appliances are being used, a custom tray would impede the planned movement of the teeth, or as the teeth moved, the trays would no longer fit. The other even bigger misconception is that using these materials, while brackets are in place, will result in a yellow spot in the center of each tooth where the bracket had been.

CP and HP can now be used to treat orthodontic patients thanks to the introduction of prefilled, disposable trays

(Opalescence Go®, Ultradent Products, Inc.) and strips (SheerWhite!®, CAO Group, South Jordan, Utah). The preloaded appliances easily adapt to fit both arches even if the teeth are malaligned. They do not exert pressure on the teeth, and they do not interfere with orthodontic movement. The misconception that CP and HP must contact every surface of the tooth to provide even whitening results was laid to rest in the early 1990s. It is well-known that CP and HP will readily penetrate the natural tooth within 5-15 minutes and will bleach under an existing restoration or bracket, although the restorative material nor bracket will be whitened. This means that even in the presence of an orthodontic bracket, the entire tooth will whiten.10

There are dentist-prescribed and -supervised products that allow the clinician to remain in control (e.g., Opalescence Go 10% and 15% hydrogen peroxide, Ultradent Products). Also available are over-the-counter products (OTCs) (e.g., Crest® White Strips, GLEEM, Proctor & Gamble, Smile™ Direct Club, Access Dental Lab), which leave the clinician out of the treatment protocol and supervision.

In reviewing some of the OTC products, packaging will state the active ingredient (i.e., hydrogen peroxide), but most fail to state the concentration of the active ingredient. Going to their websites does not reveal the concentration of the bleaching agent either. With new packaging comes different concentrations of the active ingredient, which makes it more confusing. Seems these whitening products fall between 5%-15% HP. As a professional, recommending an OTC proves difficult because the concentration of the active ingredient is not readily known. Crest White Strips states on the packaging: “Do not use on loose teeth, restorations, or braces.” GLEEM states on the FAQ section on its website: “GLEEM whitening treatments should not be used with braces because they will only whiten the parts of the teeth which the whitening gel comes into contact with. As braces cover some parts of the tooth, these parts will not whiten, leaving unevenly colored teeth when the braces are removed. Also, GLEEM whitening treatments may change the color of the metal.”17 These OTC products are effective in whitening and will, in fact, work on orthodontic patients, but because they are not using well-founded and well-known research on which to base their instructions and not stating the concentration of the active ingredient, it puts the professional at risk for recommending one.

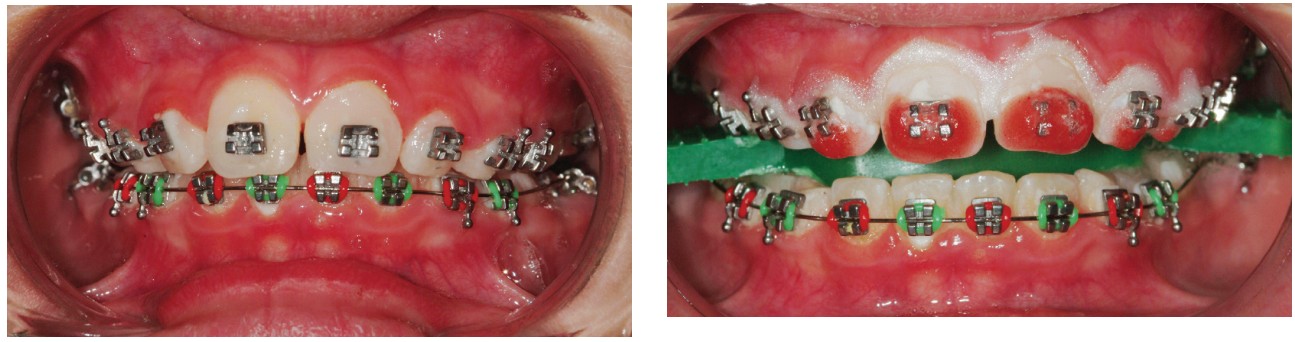

Dentist-prescribed and -supervised prefilled trays incorporating both hydrogen peroxide as well as potassium nitrate (P) and neutral sodium fluoride (F) can be found in Opalescence Go (OG). These are prefilled, adaptable, disposable trays with either 10% or 15% hydrogen peroxide gel with PF (Figure 3). These trays easily adapt to and around the orthodontic appliance (Figures 4 to 6). The patient wears the OG 10% HP trays for only 30-60 minutes per day, whereas the OG 15% HP tray is worn for 15-20 minutes per day. Although the bleach will whiten the teeth even under the brackets, there is no effect to the existing bond. The patient will benefit from the whitening effects of these products as well as other benefits of decreasing plaque formation, inflammation, decalcification, and decay. The addition of PF to hydrogen peroxide and carbamide peroxide bleaching agents has created an even greater ability of these bleaching agents to improve the health of the teeth while preventing or diminishing sensitivity. Besides decreasing the incidence of sensitivity from bleaching, research has shown an improvement in the microhardness of the enamel with this combination.

The benefits of fluoride are well-known — it is lethal to bacteria, aids in the remineralization of enamel, and forms fluorapatite, which is more acid-resistant than hydroxyapatite. Warburg and Christian reported in 1941 that the benefits of fluoride are due to the inhibition of enolase., The fluoride inhibition of enolase is important in the treatment of dental plaque in which deep layers are highly anaerobic and dependent on glycolysis for energy requirements. Fluoride also has long-term desensitizing effects. Fluoride’s desensitizing effects come from its ability to block the tubules and slow the flow of fluid that causes sensitivity. Potassium nitrate is also a desensitizing agent and has been used in toothpastes (e.g., Sensodyne®, GlaxoSmithKline U.S.) for many years. Potassium nitrate easily penetrates the tooth similarly to hydrogen peroxide and has a direct effect on the nerve. It interrupts the pain cycle by preventing the nerve from repolarizing after it has depolarized.13 It is used primarily for acute sensitivity. It’s easy to see why the addition of PF to bleaching agents has been groundbreaking.

With more orthodontic offices providing professional cleanings by hygienists, another motivational opportunity is created. In-office or “power bleaching,” as some call it, can be done by hygienists in most states. At-home prefilled trays provide more benefits of decreasing plaque formation, inflammation, etc., because they can be used several days in a row and for multiple treatments. In-office bleaching may be used as a reward for those patients who are exhibiting excellent oral hygiene. The hydrogen peroxide will bleach under the brackets without affecting the existing bond strengths in the same way that the above-mentioned trays do. A side benefit of both in-office and home-bleaching methods is that stain from around and on porcelain brackets is removed. This falls perfectly into the esthetic needs of the patient who has opted for an esthetic bracket because their appearance is ultimately important to them even during orthodontic treatment.

Case presentation

An 11-year-old male patient had been in orthodontic treatment for several months when he inquired about the possibility of whitening his teeth during treatment. There were no contraindications to bleaching his teeth even, though he was in mixed dentition. Bleaching can always be done again after the remaining permanent teeth erupt. Based on information reported by Scherer, et al., patients appeared to be motivated in their oral hygiene home care during and after bleaching their teeth. Considering this patient’s oral hygiene was fair, we expected to see improvement post bleaching. The orthodontic wire was removed, and the patient’s lips were moistened with lip balm. The teeth were isolated using cheek retractors (KleerView™ cheek retractor, Ultradent Products, S. Jordan, Utah) (Figure 7). A combination bite block-tongue retractor (IsoBlock™, Ultradent Products, S. Jordan, Utah) was then placed. The gingival tissue was then air dried, and a resin gingival barrier (OpalDam™, Ultradent Products, S. Jordan, Utah) was syringed onto the gingival margins of the teeth to be bleached overlapping approximately 1 mm onto the teeth. The barrier was also extended one tooth beyond where the bleach was to be placed. After placement, the resin barrier was light cured. The gingival barrier replaced the need for a rubber dam, thereby saving time and making the procedure more comfortable for the patient.

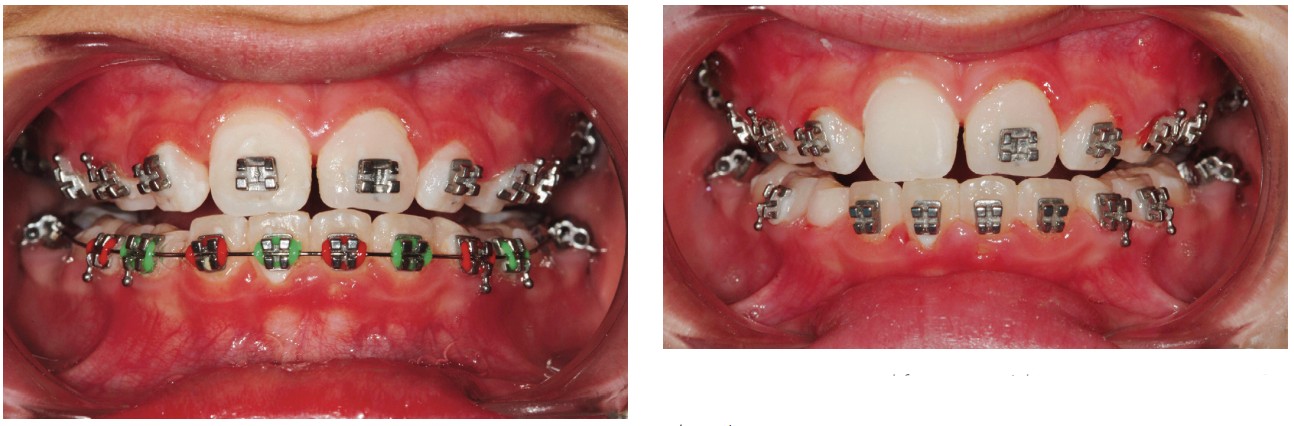

After isolation was completed, the chemically activated 40% hydrogen peroxide bleaching agent (Opalescence™ Boost™, (Ultradent Products, S. Jordan, Utah) was mixed using a syringe to syringe method; no mixing pads necessary. To show how the bleaching agent travels once it penetrates the tooth as well as how effective it is, it was only syringed onto the incisal one-half of the teeth (Figure 8). The gel was kept off the gingival barrier to prevent accidental contact with the soft tissue. The gel was left on the teeth for 15 minutes, removed, and reapplied for a total of two cycles. Normally, a four-cycle regimen of 15 minutes each would have been used, but due to the patient’s young age, it was decided that two cycles would be enough for one treatment. The gel was removed between applications without rinsing in between. Once the second application was removed, the teeth were thoroughly rinsed, and high-volume suction was used. The gingival barrier was removed followed by another thorough rinse (Figure 9). Although HP and CP bleaching agents do not affect existing bond strengths, research has shown it is necessary to wait at least 7 days after bleaching to initiate any new bonding including repositioning brackets. Three weeks after the bleaching treatment, this patient returned to the office for evaluation of the bleaching effects. A bracket was removed to show there was no dark area where the bracket had been, and where the bleach did not have direct contact with the surface of the tooth. By comparing the maxillary bleached teeth with the mandibular unbleached teeth, a significant whitening effect was obvious (Figure 10).

It’s important to remember not only the health issues associated with patients undergoing orthodontic treatment, but also their esthetic needs during and after treatment. Appealing to their desires for esthetic enhancement may be one of the most effective means to also improving the health of the soft tissues and protecting the teeth by increasing the micro-hardness of the enamel making them less impervious to decay. At-home tray delivery utilizing prefilled adaptable disposable trays or by providing in-office treatments are excellent and easy methods of getting your patients to be more diligent with their oral hygiene efforts.

Smile bleaching and esthetics influence orthodontic patients. See how esthetics entered into Dr. Jeffrey Heinz’s treatment of his own mother with clear aligners in his article “Pushing the limits.” https://orthopracticeus.com/pushing-the-limits/

References

- Proffit WR, Fields HW Jr, Sarver DM. Contemporary Orthodontics, 4th ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Øgaard B, Larsson E, Henriksson T, Birkhed D, Bishara SE. Effects of combined application of antimicrobial and fluoride varnishes in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120(1):28-35.

- Krasniqi S, Sejdini M, Stubljar D, et al. Antimicrobial Effect of Orthodontic Materials on Cariogenic Bacteria Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2020;21:26.

- Bentley CD, Leonard R, Crawford JJ. Effect of whitening agents containing carbamide peroxide on cariogenic bacteria. J Esthet Dent. 2000;12(1):33-37.

- Shapiro WB, Kaslick RS, Chasens Al, Eisenberg R. The influence of urea peroxide gel on plaque, calculus and chronic gingival inflammation. J Periodontol.1973;44:636-639.

- Reddy J, Salkin LM. The effect of a urea peroxide rinse on dental plaque and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1976;47:607-610.

- Zinner DD, Duany LF, Chilton NW. Controlled study of the clinical effectiveness of a new oxygen gel on plaque, oral debris and gingival inflammation. Pharmacol Ther Dent. 1970;1:7-15.

- Shipman B, Cohen E, Kaslick RS. The effect of a urea peroxide gel on plaque deposits and gingival status. J Periodontol.1971;42:283-285.

- Napimoga MH, de Oliveira R, Reis AF, et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of peroxide-based bleaching agents. Quintessence Int.2007;38:329-333.

- Gurgan S, Bolay S, Alacam R. Antibacterial activity of 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching agents. J Endod. 1996;22:356-357.

- Haywood VB, Parker MH. Nightguard vital bleaching beneath existing porcelain veneers: a case report. Quintessence Int.1999;30(11):743-747.

- Haywood VB, Leech T, Heymann HO, Crumpler D, Bruggers K. Nightguard vital bleaching: effects on enamel surface texture and diffusion. Quintessence Int. 1990;21(10):801-804.

- Haywood VB, Heymann HO. Nightguard vital bleaching: how safe is it? Quintessence Int. 1991;22(7):515-523.

- Morgan JA, Presley S. In-office “power” bleaching of vital teeth as an adjunct to at-home bleaching. Advanced Tooth Whitening: A comprehensive Guide to Whitening. Prac Perio & Aesthet Dent. 2002;14(suppl 2):16-23.

- Morgan JA. Striking the right balance; Trends in tooth bleaching. Dent Equip Materials. 2003;May/June:74-76.

- Morgan JA. Orthodontics with a twist: bleaching, bonding, and gingival recontouring. J Amer Orthodontic Society. 2005;5(2):20-23.

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). https://gleem.com/faq/#whitening-kit34. Accessed April 24, 2022.

- Summitt JB, Robbins JW, Schwartz RS. Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry: A Contemporary Approach. 2nd ed. Quintessence; 2001.

- Al-Qunaian TA. The effect of whitening agents on caries susceptibility of human enamel. Oper Dent. 2005;30(2)265-270.

- Warburg O, Christian W. Isolierung und Krstallisation des Garungsferments Enolase. Die Naturwissenschaften. 1941;29(39):589-590.

- Qin J, Chai G, Brewer JM, Lovelace L, Lebioda L. Fluoride inhibition of enolase: Crystal structure and thermodynamics. 2006;45(3):793-800.

- Hata S, Iwami Y, Kamiyama K, Yamada T. Biochemical mechanisms of enhanced inhibition of fluoride on the anaerobic sugar metabolism by Streptococcus sanguis.J Dent Res. 1990;69(6):1244-1247.

- Scherer W, Palat M, Hittelman E, Putter H, Cooper H. At-home bleaching system: Effect on gingival tissue. J Esthet Dent. 1992;4(3):86-89.

- Morgan-Godwin JA, Barghi N, Berry TG, Knight GT, Hummert TW. Time duration for dissipation of bleaching effects before enamel bonding. J Dent Res. 1992;71:A590.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Jaimeé Morgan, DDS, received her dental degree from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She was recently named one of the top 25 women in Dentistry. She divides her professional career between clinical practice and teaching. Her lectures have spanned the globe from the United States to Europe, South America, Australia, and Asia. She regularly contributes articles on cosmetic dental techniques for the general practice. She served as a founding member of the South Texas Chapter of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. Salt Lake City, Utah, is the site of her dental practice where she provides cosmetic and restorative dentistry with her husband Dr. Stan Presley. Dr. Morgan has earned the reputation of teaching cosmetic techniques using a practical approach that is both enjoyable and useful.

Jaimeé Morgan, DDS, received her dental degree from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She was recently named one of the top 25 women in Dentistry. She divides her professional career between clinical practice and teaching. Her lectures have spanned the globe from the United States to Europe, South America, Australia, and Asia. She regularly contributes articles on cosmetic dental techniques for the general practice. She served as a founding member of the South Texas Chapter of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. Salt Lake City, Utah, is the site of her dental practice where she provides cosmetic and restorative dentistry with her husband Dr. Stan Presley. Dr. Morgan has earned the reputation of teaching cosmetic techniques using a practical approach that is both enjoyable and useful. Stan Presley, DDS, received his dental degree from Baylor College of Dentistry in 1977. His training at the L.D. Pankey Institute has provided him with a sound cosmetic treatment philosophy. Dr. Presley was one of the founding members of the South Texas Chapter of the AACD where he served as secretary and vice-president. In recognition of the need to provide an alternative to porcelain restorations in his practice, Dr. Presley focused his attention on conservative esthetic restoration combined with orthodontic treatment. He is co-developer of the Simplified Layering Technique for composites along with his wife, Dr. Jaimeé Morgan. Dr. Presley lectures internationally using both didactic and hands-on courses and has contributed numerous articles demonstrating realistic and learnable procedures for general practitioners. He currently practices cosmetic and restorative dentistry with his wife Dr. Jaimeé Morgan at Morgan & Presely Dental in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Stan Presley, DDS, received his dental degree from Baylor College of Dentistry in 1977. His training at the L.D. Pankey Institute has provided him with a sound cosmetic treatment philosophy. Dr. Presley was one of the founding members of the South Texas Chapter of the AACD where he served as secretary and vice-president. In recognition of the need to provide an alternative to porcelain restorations in his practice, Dr. Presley focused his attention on conservative esthetic restoration combined with orthodontic treatment. He is co-developer of the Simplified Layering Technique for composites along with his wife, Dr. Jaimeé Morgan. Dr. Presley lectures internationally using both didactic and hands-on courses and has contributed numerous articles demonstrating realistic and learnable procedures for general practitioners. He currently practices cosmetic and restorative dentistry with his wife Dr. Jaimeé Morgan at Morgan & Presely Dental in Salt Lake City, Utah.