Dr. Robert Kaspers shows how CBCT imaging technology can help to detect vertical discrepancies in a patient’s occlusion.

Dr. Robert Kaspers notes that interaction between dentists and orthodontists can result in more effective treatment

Unfortunately, dental schools do not educate general dentists on why certain patients need orthodontists. And aligner companies’ marketing has done a phenomenal job in informing general dentists about how easy it is to move teeth with aligners. Unfortunately, the dentist is not educated to the limitations of aligners in treating the three dimensions (anterior-posterior, transverse, and vertical). Diagnosis is everything when it comes to getting a successful orthodontic result. With the advent of CBCT scans, analysis of the three dimensions is easier than ever. With the proper imaging for accurate diagnosis, general dentists and orthodontists can recognize which patients can benefit from aligner therapy and which need an orthodontic specialist for the more effective treatment for the patient.

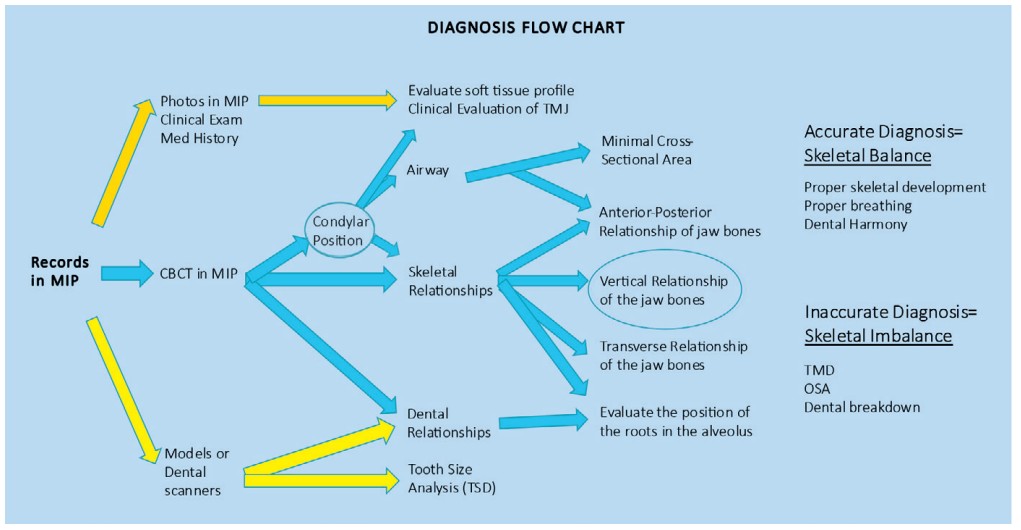

The diagnosis flow chart (Figure 1) displays all the areas that a 3D radiograph can explore and gain valuable information to complete an accurate diagnosis.

Without a CBCT scan, the dentist or orthodontist has no idea if the condyles are properly seated in the glenoid fossa. What may appear “clinically” to be an easy adjustment with an aligner may actually be a clinical symptom of a much bigger concern.

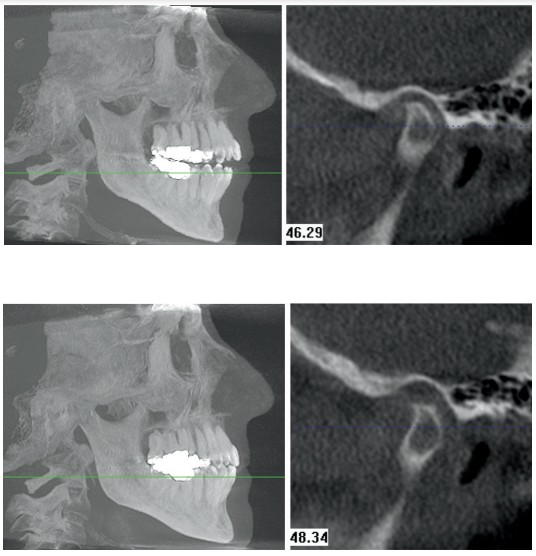

The patient in Figure 2 had braces by an orthodontist and, unfortunately, began having headaches and pain with her masseter muscles. The CBCT scan showed both condyles to be in a retruded-and-down condylar position. Because the orthodontist did not take a CBCT scan on the patient, he was unaware that the patient was fulcrumming around posterior interferences to achieve maximum intercuspation.

The advent of 3D technology has allowed the clinician to detect vertical discrepancies in a patient’s occlusion. Prior to the CBCT scan, the clinician could determine the patient’s condylar position by mounting the case on a SAM II articulator utilizing a CPI (condylar position indicator).1 However, the process was too labor-intensive requiring a highly skilled clinician.

An increase in the vertical dimension of the superior joint space informs the clinician that the patient is fulcrumming around a posterior interference. Roth defined the fulcrum as a condition in which the condyle distracts away from the eminence when the mandible closes into maximum intercuspation.2 When we talk about the “vertical dimension,” we must address it in two areas:

- the vertical dimension with the condylar position in the glenoid fossa

- the vertical dimension in the patient’s occlusion

The patient pictured in Figure 2 had both condyles in a retruded-and-down position, which means there was an increase in the superior joint space. Loading the temporomandibular joints properly with a bite plate seated the condyles in the glenoid fossae. However, changing the vertical discrepancy in the glenoid fossa will change the vertical dimension in the patient’s occlusion. One affects the other as you can see in Figure 3. Seating the condyles with a properly constructed bite plate produced an anterior open bite.

Most importantly, an orthodontist must inform the dentist that correction of the “fulcrum effect” must be achieved in adult patients by properly loading the temporomandibular joints throughout orthodontic therapy. Without maintaining a seated condylar position throughout treatment, the patient will attempt to acquire maximum intercuspation for stability.

If patients are allowed to “fulcrum around a posterior interference” during their orthodontic therapy, there is an excellent chance that the clinician will not acquire a seated condylar position at the end of treatment. The clinician must understand that an oral appliance such as a bite plate, splint, or a custom NTI may be utilized to help maintain a seated condylar position and a healthy musculature during orthodontic therapy (Figure 5). Intrusion of the maxillary molars can eliminate the fulcrum point and allow the mandible to auto-rotate closed.

An MRI scan of an adult fulcrumming around a posterior interference will usually show an increase in tissue surrounding the disc. The body does not leave a void when the condyle distracts away from the eminence. Instead, it fills the void with tissue, which will maintain the “retruded-and-down” position. Hand manipulation may get the clinician close to seating the condyle within the glenoid fossa, but the condyle will not remain seated as the tissue influences the position of the condyle. The MRI scan (Figure 4) shows both temporomandibular joints of a patient possessing discs that are at the 12:00 position. The patient’s right condyle is in a centered-and-down condylar position, while the left condyle is forward on the eminence. The MRI scan shows the anterior joint space twice as wide with the centered-and-down condylar position as compared to the condyle forward on the eminence.

The information gained from an MRI scan is extremely helpful in verifying disc position as well as whether or not inflammation is present within the joint complex. However, the CBCT scan is more helpful to the orthodontist because the clinician can assess whether or not the condyle is seated in the glenoid fossa as explained by Ikeda3 but can also evaluate how the condylar position affects the patient’s occlusion and vice versa.

The two CBCT scans in Figures 6 and 7 were taken 2 minutes apart with and without a maxillary occlusal splint. The patient had been receiving splint therapy for months, and the CBCT scan verified a seated condylar position (Figure 6). A second CBCT scan was taken immediately after the first scan to evaluate the vertical discrepancy. The maxillary occlusal splint was removed, and the patient was asked to close down into maximum intercuspation (Figure 7). These two CBCT scans clearly show the clinician how a scan can become a “functional radiograph.” By taking the CBCT scan in MIP, the clinician gets to see how the patient’s occlusion and musculature can influence the condylar position. Having an understanding of the condylar position helps the orthodontist treat the dentist’s patients to a seated condylar position.

Correction of the vertical discrepancy shown in this last patient cannot be corrected with aligner therapy. Dentists need to be informed by their orthodontists that intrusion mechanics should be utilized to correct the vertical dimension. If your referring dentists do not possess a CBCT scan, you should take them out to lunch, so you can show them how the CBCT scan can help diagnose their patients correctly.

Dr. Kaspers also touted CBCT technology in a past article, “Keep Learning!” Read it here: https://orthopracticeus.com/keep-learning/

- Cordray FE. Three-dimensional analysis of models articulated in the seated condylar position from a deprogrammed asymptomatic population: a prospective study. Part 1. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5):619-630.

- Roth RH, Rolfs DA. Functional occlusion for the orthodontist. Part II. J Clin Orthod. 1981;15(2):100-123.

- Ikeda K, Kawamura A. Assessment of optimal condylar position with limited cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(4):495-501.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores