Dr. Rohit C.L. Sachdeva discusses the eight major forces shaping the future of orthodontics

The development of the orthodontic specialty has generally followed the cultural, scientific, and technological evolution of society, although it has not necessarily always been in step. The historical transformation of our society to the present time has clear footprints. The agrarian society was symbolized by the farmer with the plough and the industrial society by the assembly-line worker. Today’s “knowledge” worker can best be characterized by the computer. Similarly, the orthodontic profession has witnessed a transformational process that I describe as Ortho 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0. Ortho 1.0 typically defined the orthodontist’s role as a craftsman whose skills lie in manual dexterity and the use of a plier to bend wire and provide personalized care. In some ways, this was no different than a farmer in an agrarian society whose skills lay in tilling the land to provide for his family. Ortho 2.0 extended the orthodontist’s role into that of a manager leading a team of chairside assistants and support staff to provide care to a broader base of patients with the use of standardized and modular orthodontic appliances. Again, one can clearly visualize parallels of this environment with that of the Henry Ford model of mass production in the early 20th century and the introduction of prefabricated modular parts assembled by a labor force. Furthermore, both the agrarian and industrial models represented an authoritarian “closed system” of management with the manager occupying a privileged position at the apex of the pyramid. Both Ortho 1.0 and 2.0 can be characterized by a hierarchical model of care delivery; i.e., a “doctor–centered” model with little participation from patients in defining their personal treatment wants or needs.

Today, we are at the beginning of an orthodontic care revolution driven by the following eight major forces poised to redefine the practice of orthodontics as we know it, including the following considerations of their impact on the profession.

Health information technology and health literacy

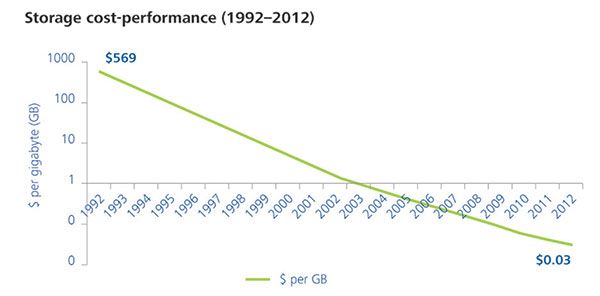

Developments in healthcare information technologies support almost instant connectivity and communication between all stakeholders in the healthcare system. The ability to transfer massive amounts of data on demand, the enablement of cost-effective data-warehousing and data-mining resources, is driving the genesis of a healthcare information exchange that is accessible to all. The increased porosity of information exchange is breaking the traditional communication barriers between patients, doctors, hospitals, academia, and industry. Healthcare is being democratized rapidly through the rise of the informed patient. This new dynamic is already leading to the reframing of the traditional roles and relationships between doctor and patient.

Computer-aided design and manufacturing and “omics” technologies/bioinformatics

The development of computer-aided design and manufacturing technologies, coupled with the biological revolution in the “omics” arena — namely, genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics — has the potential to provide unprecedented abilities to the orthodontist in designing and delivering personalized and targeted care to patients.

Public policy

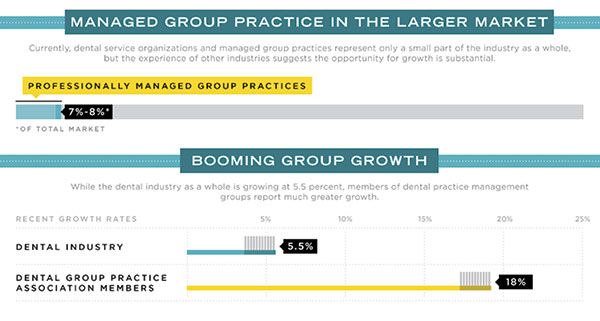

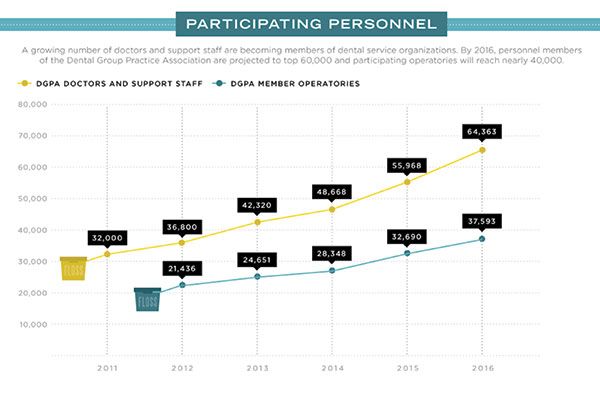

Western economies are crumbling under the weight of high healthcare costs, especially in the United States. Public policy, driven by government agencies, the insurance industry, and the patient communities at large, is demanding high fidelity and quality care. In other words, care delivery is effective, efficient, patient-centered, safe, affordable, and value-driven (Figures 3 and 4). Additionally, the pressures from these agencies are requiring the doctor to be more transparent and accountable for the care given to patients. Finally, in the race to provide value-based care through the economies of scale, we are witnessing a proliferation of managed-care dental practices that are challenging the role of the solo practitioner (Figures 1 and 2).

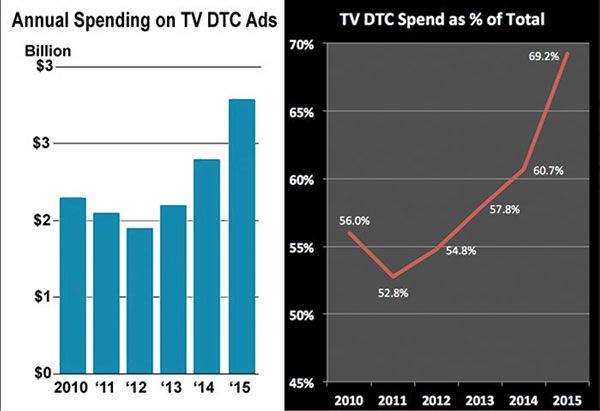

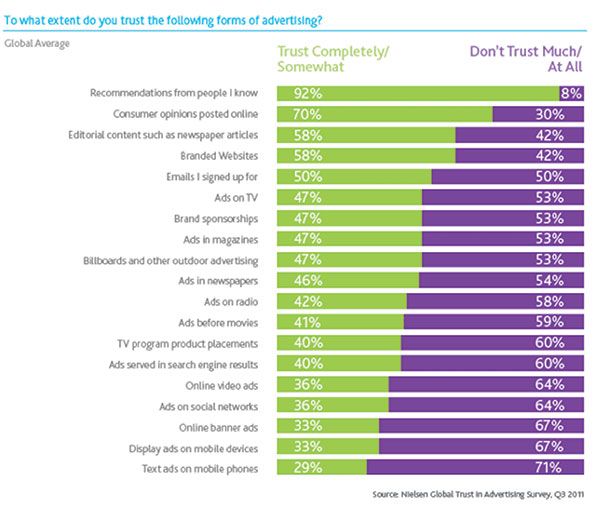

Direct-to-consumer marketing and social networks

Bypass marketing efforts by industry are challenging the traditional role of the doctor as the legitimate source of healthcare-related information to patients (Figures 5 and 6). Furthermore, the rapid proliferation of support groups on the Internet is extending their reach and influencing the mind-set of patients through conversations of “real-world” care experiences and disease-specific resources of information.

The rise of the expert non-expert

The rise of the generalist dental practitioner is upsetting the traditional role of the specialist orthodontist in providing orthodontic care. Adding to the fuel is the almost pervasive lack of recognition by patients regarding the professional capabilities of the specialist orthodontist. Furthermore, the generalist is equipped to address the needs of a patient as a “whole,” with comprehensive dental treatment adding to the convenience of care under “one roof.” All these factors unfortunately bring into question the value of specialist education.

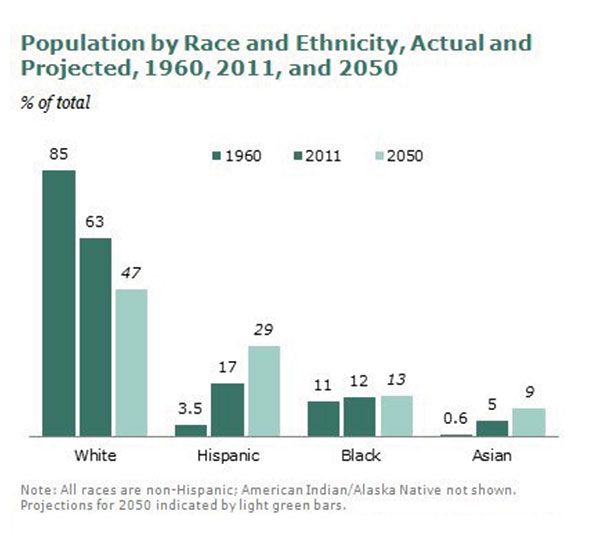

The shift in patient demographics

In the western world, we are witnessing a significant decline in birthrates and, concurrently, a rise in the aging population as well as growth in the immigrant population. These dynamics represent a shift in the patient population base and demand that the specialist attune his practice to deal with patients whose needs and aspirations for orthodontic care are very different from the traditional teenager. The demand of care for the geriatric population is generally limited in nature, and furthermore, many of these patients are afflicted with chronic diseases requiring a total healthcare approach in managing them effectively. The first-generation ethnic population is generally not as well acquainted with the benefits of ortho-dontic care and require novel approaches in communication to encourage their participation in care (Figure 7).

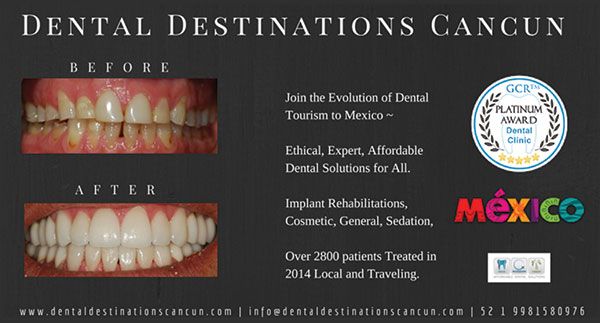

Rise of dental tourism

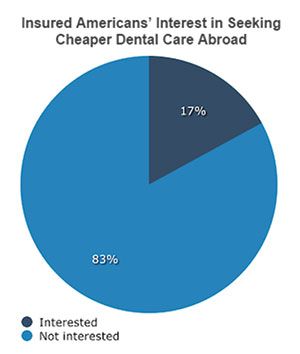

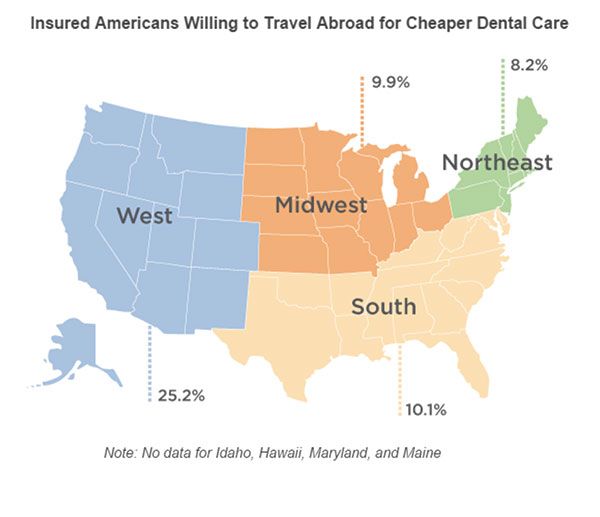

The “repackaging” of dental care as an esthetic need rather than a health need in the western world, combined with cost pressures and globalization of expertise, are defining new channels for affordable patient care. It is highly conceivable that patients will have access to orthodontic care from orthodontic practitioners “beyond borders,” especially when it comes to providing limited care with aligners. And such a model could easily be offered under the auspices of dental tourism. In fact, the more the clinician relies upon outsourcing planning of care by external agencies (laboratories) for patients, especially in the arena of digital orthodontics, the greater the likelihood of such a model gaining a foothold (Figures 3, 8, and 9).

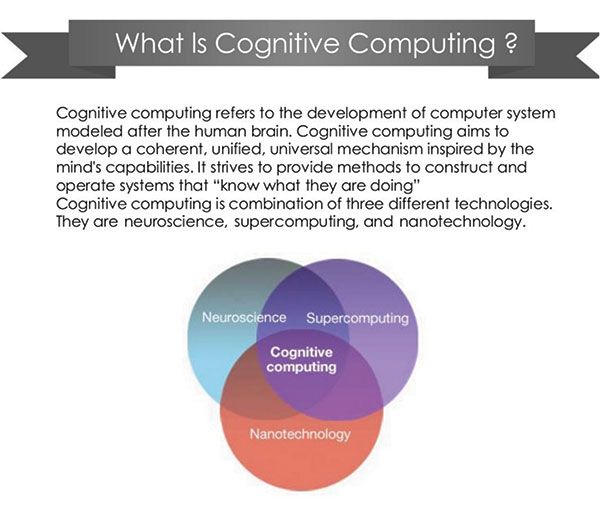

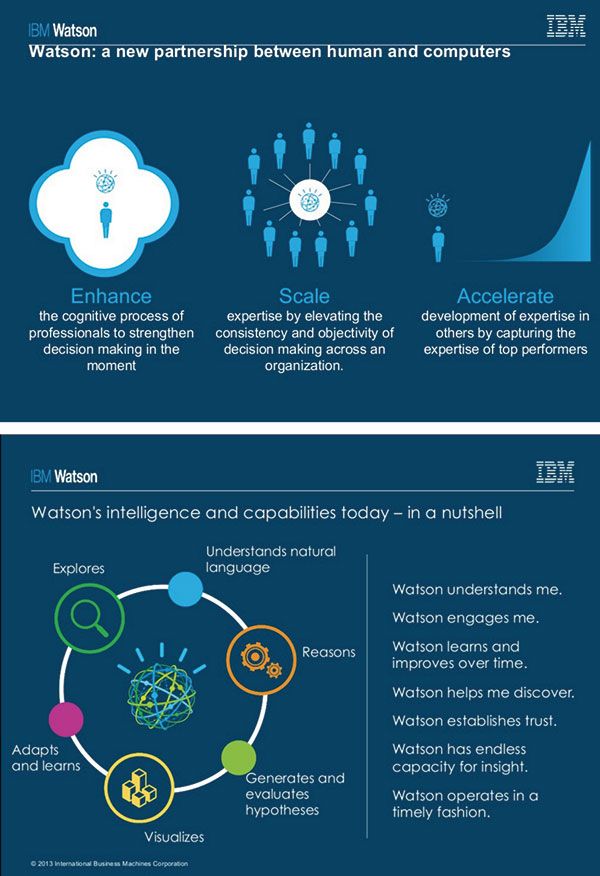

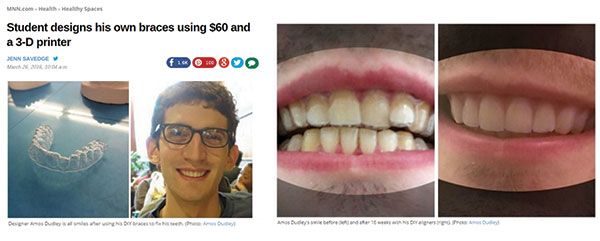

Do-it-yourself (DIY)/IKEA orthodontics in the era of cognitive computing

We are rapidly approaching the era of cognitive computing driven by transformational developments in the area of artificial intelligence (Figures 10, 11, and 12). A real-world product of this technology is Google’s autonomous car. I believe in the next couple of decades, it will be possible to use the power of machine intelligence through input provided directly by the patient to design a care plan. Orthodontic appliances would be directly manufactured in the “home lab” with the use of computer-aided manufacturing such as 3D printing. And patients could manage their personal care by scanning themselves periodically and matching their response against a guidance or tracking system based upon patient-matched data. This “DIY/IKEA orthodontics” is a real possibility. In fact, the ability to design and manage one’s own care was recently demonstrated by a design student, Amos Dudley1 (Figure 13).

The orthodontic profession is at a crossroads. The dilemma lies in recognizing the new realities “on the ground” and the need to evolve into an environment that is more system-based. This will undoubtedly come at a price and loss of some professional autonomy in order to achieve greater good.

Furthermore, the orthodontist will need to commit to acquiring new knowledge and skills through personal drive in order to harness the promise of new learning and technologies to improve patient care, to increase its accessibility while remaining mindful of the cost and, most importantly, to maintain professional dignity and be the font of empathy for every patient.

Ortho 3.0 defines this “New Look” for our profession, moving beyond the monolithic symbolism of the computer and the image of the orthodontist practicing in solitude behind a desktop, always distanced from patients by cyberspace.

Ortho 3.0 places the patient at the epicenter of the care-delivery model with all other actors and agencies coalescing within a system designed to serve the patient as an individual. It is designed around system-based thinking that continuously strives to improve patient care, to enhance both personal and community care through the practices of a learning/teaching organization, to employ evidence-based clinical practices, to offer highly reliable organization and care management, to support and advance patient healthcare literacy, and engagement, as well as achieving truly connected care.

Ortho 3.0 challenges conventional models and ways of thinking of orthodontic care delivery, while seeking transformational leadership, new awakenings through patient participation, interprofessional and transdisciplinary collaborations, and new learning that will redesign the orthodontic care system.

Ortho 3.0 can only gain a foothold through a spirit of collective professional resolve that is supported by the backbone of professional antifragility. This mandates growth through deliberate experimentation fueled by intelligent failure.

Yes, in some ways, it is a departure from the past. Yet in many ways, it retains the core values, belief systems, and some of the practices of conventional orthodontics. To state it explicitly: “patients matter.” This does not and will not change.

Aeger Primo, patients first.

- Fiona MacDonald. A college student has 3D-printed his own braces for less than $60. Science Alert. https://www.sciencealert.com/a-college-student-has-3d-printed-his-own-braces-for-less-than-60. Published March 21, 2016. Accessed May 31, 2016.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Rohit C.L. Sachdeva, BDS, M Dent Sc, is a consultant/coach with Rohit Sachdeva Orthodontic Coaching and Consulting, which helps doctors increase their clinical performance and assess technology for clinical use. He also works with the dental industry in product design and development. He is the co-founder of the Institute of Orthodontic Care Improvement. Dr. Sachdeva is the co-founder and former Chief Clinical Officer at OraMetrix, Inc. He received his dental degree from the University of Nairobi, Kenya, in 1978. He earned his Certificate in Orthodontics and Masters in Dental Science at the University of Connecticut in 1983. Dr. Sachdeva is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics and is an active member of the American Association of Orthodontics. In the past, he has held faculty positions at the University of Connecticut, Manitoba, and the Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M. Dr. Sachdeva has over 90 patents, is the recipient of the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science Award, and has over 160 papers and abstracts to his credit. Visit Dr. Sachdeva’s blog on

Rohit C.L. Sachdeva, BDS, M Dent Sc, is a consultant/coach with Rohit Sachdeva Orthodontic Coaching and Consulting, which helps doctors increase their clinical performance and assess technology for clinical use. He also works with the dental industry in product design and development. He is the co-founder of the Institute of Orthodontic Care Improvement. Dr. Sachdeva is the co-founder and former Chief Clinical Officer at OraMetrix, Inc. He received his dental degree from the University of Nairobi, Kenya, in 1978. He earned his Certificate in Orthodontics and Masters in Dental Science at the University of Connecticut in 1983. Dr. Sachdeva is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics and is an active member of the American Association of Orthodontics. In the past, he has held faculty positions at the University of Connecticut, Manitoba, and the Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M. Dr. Sachdeva has over 90 patents, is the recipient of the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science Award, and has over 160 papers and abstracts to his credit. Visit Dr. Sachdeva’s blog on