Dr. Emad Hussein and colleagues illustrate how to avoid orthognathic surgery by using miniscrews for skeletal anchorage.

Drs. Emad Hussein, Sari Amer, Yazan Ashhab, Khaled Qattawi, Mohammad Abo Mowais, Nezar Watted, Zuhir Anani, and Manal Samarah treat a challenging malocclusion

A height angle Class II malocclusion is one of the most challenging malocclusions to treat, especially for adult patients. Orthodontic treatment is seldom sufficient alone in treating this type of craniofacial pattern and typically requires orthognathic surgery.

The nature of a Class II malocclusion with a hyperdivergent mandible is mechanics-sensitive since straightwire appliances are usually extrusive, which will aggravate the backward and downward position of the mandible, thus making the Class II malocclusion worse.1-3 Controlling the vertical position of posterior teeth is an important factor in treating these patients.4-5 In growing patients, vertical control can be achieved with a high-pull headgear and molar bite blocks.6-10 Adults, especially those with open bites, cannot be treated easily without orthognathic surgery.

Still, skeletal anchorage with miniscrews makes the vertical control of the posterior dentition possible and even their intrusion and retraction. In many cases, this can eliminate the need for orthognathic surgery.11-13

Interradicular miniscrews have been used successfully to intrude posterior teeth,14-16 but in Class II high-angle patients, they have not been effective in the retraction of those teeth — hence, the introduction of longer infrazygomatic miniscrews, which allow both intrusion and retraction maxillary buccal segments. This also allows the mandible to autorotate in a counterclockwise manner, which facilitates the treatment of Class II hyperdivergent patients.17-20

The current clinical report successfully uses infragomatic miniscrews to intrude and retract posterior segments in an adult high-angle Class II malocclusion, which also succeeded in the correction of sagittal, transverse, and vertical discrepancies.

Patient history and examination

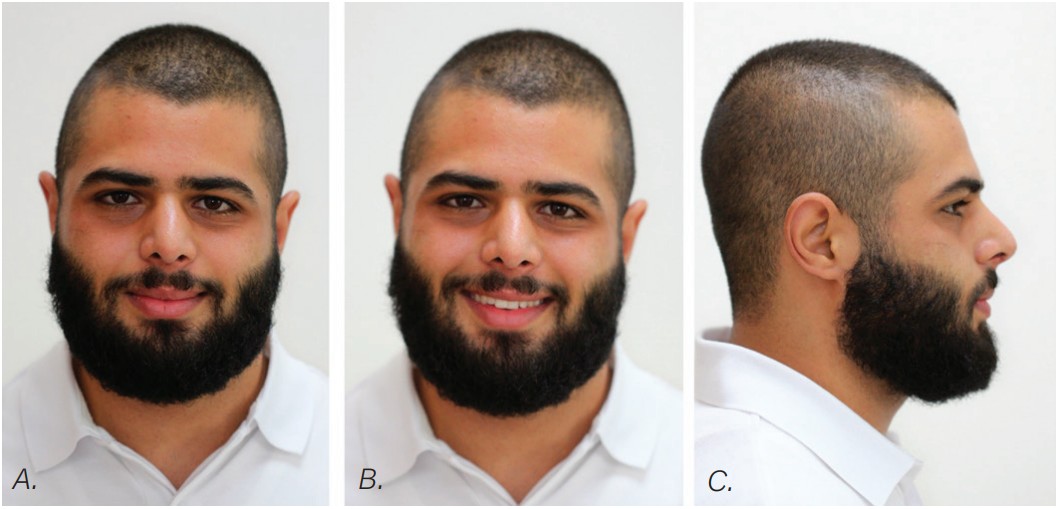

A 19-year-old healthy male patient presented to our clinic with a chief complaint of protruded teething and open bite. The patient had a symmetric face, competent lips, and an increased lower anterior face height. His profile was convex due to the mandibular recursion aggravated by a clockwise rotation, which increased the convexity. The nasolabial angle was obtuse (Figures 1A-1C).

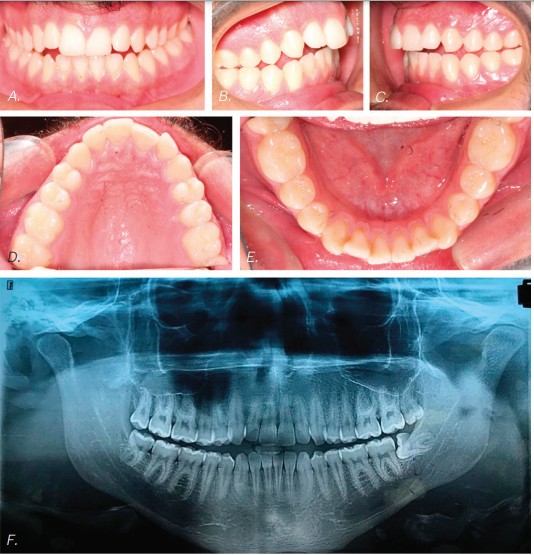

A smile analysis revealed a reverse smile line and an insufficient display of maxillary incisors upon smiling. Intraorally, he had an open bite with proclaimed maxillary incisors, a constricted maxillary arch, and a bilateral posterior crossbite. He also had Class II molars and canines on both sides. The occlusal view showed a tapered maxillary arch and a round-shaped mandibular arch. Both arches displayed arch length discrepancies (Figures 2A-2E).

Radiographic examination

The panoramic X-ray showed a full complement of teeth, a left horizontally impacted third molar, along with the three other third molars (Figure 2F). The pretreatment cephalometric analysis revealed a skeletal Class II measurement of an ANB of 6.8° with a retrognathic mandible measuring aSNB of 76.6°. The mandible had a hyperdivergent growth pattern of 58.35% with a long anterior face height of 130.6 mm (Figure 3A). The maxillary incisors showed protrusion of .9.5mm to APOg with a proclination of 115.8°, while the mandibular incisors were retrusive with an APOg measurement of .4 mm and retroclined to 84°.

Treatment plan and therapeutic options

A surgical option to intrude the maxillary dentition with a mandibular advancement was offered but refused by the patient. An option was then offered and accepted by the patient to use infra-zygomatic miniscrews to intrude and retract the maxillary teeth.

Treatment started with a transpalatal arch between the maxillary first molars, which acted as a rigid unit to prevent unwanted facial inclination of the molars. A referral was made to an oral surgeon to remove the third molars. Fixed appliances of .022 x .028 Pinnacle® brackets with the McLaughlin, Bennett & Trevisi Prescription from Ortho Technology® were bonded to maxillary and mandibular teeth, and .014 thermal nickel-titanium full-form archwires (TruFlex®, Ortho Technology®, West Columbia, South Carolina) were used to align the arches after which a .016 stainless steel maxillary TruForce™ wire (Ortho Technology®) was placed. Following the stainless steel wire, two Vector TAS infrazygomatic miniscrews (Ormco™ Corporation, Orange, California) were inserted between the first and second maxillary molars (Figures 4A-4E).

Power chains with approximately 150 grams-force were added from the miniscrews to the maxillary first molars. After a .019 x .025 TruForce™ stainless steel archwire was placed in the maxillary arch, an additional power chain connected the maxillary canines to the miniscrews to retract as well as to intrude the posterior buccal segments without jeopardizing the inclination of the maxillary anterior teeth. The patient refused the use of miniscrews in the mandibular arch, so molar bite blocks (Reliance® Ultra Band-Lock, Ortho Technology®) controlled the vertical position of the mandibular molars, which prevented them from over eruption.

One-eighth inch vertical elastics (Amber medium 1/8 inch Manta Ray®, Ortho Technology®) and Class II 3/16 inch medium elastics (3/16 medium Sea Otter®, Ortho Technology®) were employed in the last stages of treatment to settle the occlusion and to improve the mandibular incisor inclination (Figures 5A-5C).

Wraparound Hawley Retainers provided retention, which encouraged further molar eruption and intercuspation. Once molar intercuspation completes, new thermoelastic refiners would be used to prevent molars from over eruption.

Treatment outcome

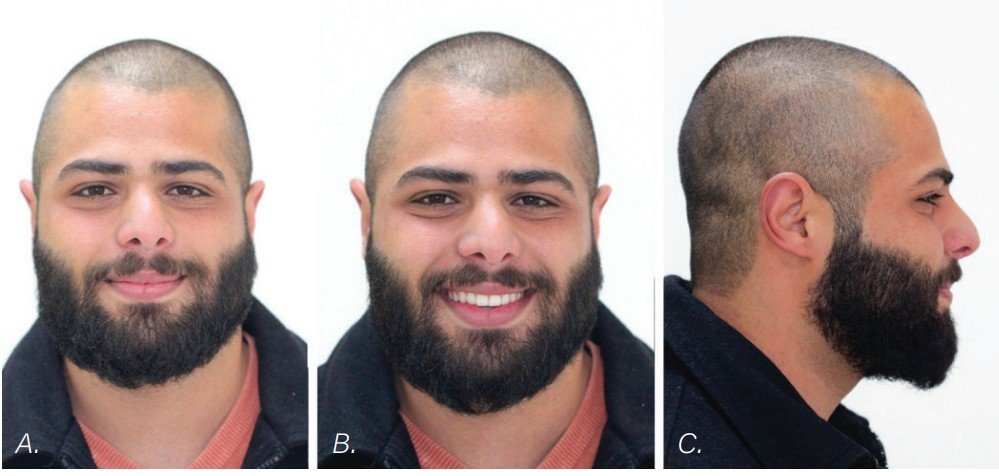

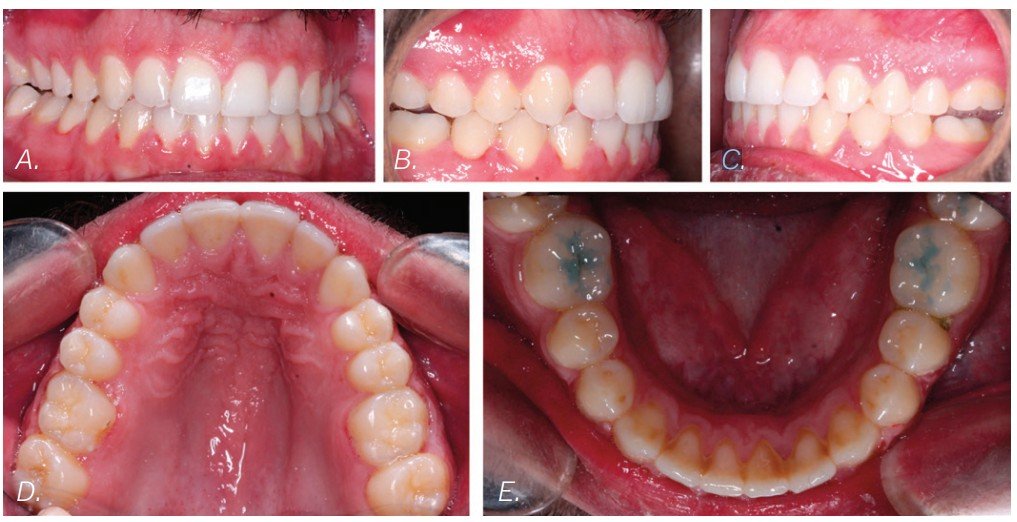

Class I molars and canines were achieved, the overjet improved, and the open bite closed. The lower anterior face height markedly decreased, and a slight advancement of the chin occurred (Figures 6 and 7). The bilateral posterior crossbites corrected, and the arch length discrepancies resolved. The smile arc now followed with the contour of the lower lip.

Cephalometric superimposition of the pre- and-post-tracings showed an overall improvement among multiple cephalometric measurements, including, but not limited to, the refinement of the maxillary and mandibular incisors’ positions. The maxillary incisors decreased their proclamation from 115° to 107.3°, and their anteroposterior position decreased from 9.5 mm to 3.4 mm. The mandibular incisor IMPA increased from 84° to 91.8°, while the anteroposterior position increased from 0.4 mm to 1.9 mm.

The lower lip to the E-line improved from the mandibular incisor proclination, and the mandibular counterclockwise rotation provided by the intrusion of the posterior maxillary segment. The patient’s anterior face height decreased dramatically by 3.07 mm. The Frankfort mandibular plane decreased by 2.7° as well as an improvement of the facial axis by 2.6°.

Conclusion

Many would consider only orthognathic surgery for a malocclusion of this sort.21-22 Still, miniscrews provided the skeletal anchorage for the successful treatment of this adult hyper-divergent Class II malocclusion complicated by a serious open bite.23-24

While Dr. Hussein and colleagues were able to avoid orthognathic surgery with miniscrews, Dr. David Alpan discusses accelerating orthodontics with orthognathic surgery. Read his CE article here, and subscribers can take the quiz and receive 2 CE credits! https://orthopracticeus.com/ce-articles/combining-accelerated-orthodontics-with-orthognathic-surgery-to-reduce-overall-treatment-time/

- Schendel SA, Eisenfeld J, Bell WH, Epker BN, Mishelevich DJ. The long face syndrome: vertical maxillary excess. Am J Orthod. 1976;70(4):398-408.

- Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM. Orthodontic diagnosis: The problem-oriented approach. In: Contemporary Orthodontics. 5th ed. Mosby; 2013.

- Inami T. The treatment of Class II malocclusions, combined with severe crowding and bimaxillary protrusion using a multi-lingual bracket appliance. J Jpn Assoc Adult Orthod. 1997;3:76-96.

- Schudy FF. The control of vertical overbite in clinical orthodontics. Angle Orthod. 1968;38(1):19-39.

- Park YC, Lee SY, Kim DH, Jee SH. Intrusion of posterior teeth using mini-screw implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123(6):690-694.

- Sankey WL, Buschang PH, English J, Owen AH 3rd. Early treatment of vertical skeletal dysplasia: the hyperdivergent phenotype. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118(3):317-327.

- Firouz M, Zernik J, Nanda R. Dental and orthopedic effects of high-pull headgear in treatment of Class II, division 1 malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102(3):197-205.

- Ngan P, Wilson S, Florman M, Wei SH. Treatment of Class II open bite in the mixed dentition with a removable functional appliance and headgear. Quintessence Int. 1992;23(5):323-333.

- Cozza P, Mucedero M, Baccetti T, Franchi L. Early orthodontic treatment of skeletal open-bite malocclusion: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2005;75(5):707-713.

- Marşan G. Effects of activator and high-pull headgear combination therapy: skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue profile changes. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29(2):140-148.

- Erverdi N, Keles A, Nanda R. The use of skeletal anchorage in open bite treatment: a cephalometric evaluation. Angle Orthod. 2004;74(3):381-390.

- Kuroda S, Sakai Y, Tamamura N, Deguchi T, Takano-Yamamoto T. Treatment of severe anterior open bite with skeletal anchorage in adults: comparison with orthognathic surgery outcomes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(5):599-605.

- Xun C, Zeng X, Wang X. Microscrew anchorage in skeletal anterior open-bite treatment. Angle Orthod. 2007;77(1):47-56.

- Park HS, Lee SK, Kwon OW. Group distal movement of teeth using microscrew implant anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2005;75(4):602-609.

- Kuroda S, Sugawara Y, Deguchi T, Kyung HM, Takano-Yamamoto T. Clinical use of miniscrew implants as orthodontic anchorage: success rates and postoperative discomfort. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:(1)9-15.

- Yamada K, Kuroda S, Deguchi T, Takano-Yamamoto T, Yamashiro T. Distal movement of maxillary molars using miniscrew anchorage in the buccal interradicular region. Angle Orthod. 2009;79(1):78-84.

- Liou EJ, Chen PH, Wang YC, Lin JC. A computed tomographic image study on the thickness of the infrazygomatic crest of the maxilla and its clinical implications for miniscrew insertion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131(3):352-356.

- Uribe F, Mehr R, Mathur A, Janakiraman N, Allareddy V. Failure rates of mini-implants placed in the infrazygomatic region. Prog Orthod. 2015;16(31).

- Murugesan A, Sivakumar A. Comparison of bone thickness in infrazygomatic crest area at various miniscrew insertion angles in Dravidian population — A cone beam computed tomography study. Int Orthod. 2020;18(1):105-114.

- Lima A Jr, Domingos RG, Cunha Ribeiro AN, Rino Neto J, de Paiva JB. Safe sites for orthodontic miniscrew insertion in the infrazygomatic crest area in different facial types: A tomographic study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022;161(1):37-45

- Ozaki, Takemasa, Shusaku Ozaki, and Kumi Kuroda. Premolar and additional first molar extraction effects on soft tissue: effects on high angle Class II division 1 patients. Angle Orthod. 2007;77(2):244-253.

- Almurtadha RH, Alhammadi MS, Fayed MMS, Abou-El-Ezz A, Halboub E. Changes in soft tissue profile after orthodontic treatment with and without extraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2018;18(3):193-202.

- Wu X, Liu H, Luo C, Li Y, Ding Y. Three-dimensional evaluation on the effect of maxillary dentition distalization with miniscrews implanted in the infrazygomatic crest. Implant Dent. 2018;27(1):22-27.

- Bayome M, Park JH, Bay C, Kook YA. Distalization of maxillary molars using temporary skeletal anchorage devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2021;24(suppl 1):103-112.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores