Dr. Gabriela Aurora Asensi discusses treatment of a special needs patient

Abstract

A case of an unexpectedly found compound odontoma discovered while treating a pediatric dental patient with autism during oral rehabilitation under general anesthesia is presented. This odontoma caused impaction of the right central maxillary incisor. This patient shows how an impacted maxillary central incisor with a completely formed root erupted into the mouth after removing its blocking odontoma which took 5 years to complete. Orthodontic extrusion was not achievable due to the patient’s inability to cooperate with orthodontic treatment. Subsequently orthodontic extrusion was not necessary. The conservative approach used with this patient shows how the teeth can erupt on their own. The patient illustrates how a conservative approach can pay off by giving patients with special needs and their caretakers hope when orthodontic treatment is not feasible because of special needs that preclude such treatment.

Introduction

Odontomas are defined as a benign tumor of odontogenic origin.1 They are basically classified into two types, complex and compound.2 Compound odontomas consist of small tooth-like structures, and complex odontomas are a conglomeration of dentin, enamel, and cementum.3 Analysis has revealed that compound odontomas, the most common type,4 are usually diagnosed in the second decade of life.5 Their presence causes interferences in tooth eruption including impaction, delayed, and/or ectopic eruption.6 Normally, there is no potential for eruption when the impacted tooth has a completely formed root or when the homologous tooth has been erupted for at least 6 months with complete root formation.7 Orthodontic extrusion is a common way to erupt impacted teeth after odontoma removal if the root is completely formed.8 However, this might not be possible with autistic children. Although malocclusions occur more often in physically and/or mentally disabled children, the most severely handicapped patients are those least likely to receive orthodontic treatment due to their uncooperative behaviors.9 This patient shows how the removal of a fortuitously found odontoma in an autistic child treated under general anesthesia by a pediatric dentist allowed an impacted maxillary right central incisor to fully form a root and erupt into the mouth. This tooth found its way into the oral cavity but took 5 years to do so.

Description

An 8-year-old Hispanic male presented to our private practice in Miami, Florida with the chief complaint of a missing front tooth (Figure 1). Upon review of his medical history, the mother revealed that her son had Autism Spectrum Disorder and confirmed that his condition was severe. This patient did not take any medications, was nonverbal, avoided eye contact with any staff member including the treating pediatric dentist, did not sit in the dental chair, and was constantly tapping his ears. No dental radiographs were obtained due to his uncooperative behavior. For the dental exam, the mother agreed and consented with placing him in a passive restraining device. With a limited visualization of his oral cavity, a mixed dentition was noted. The maxillary right permanent central incisor was absent. No significant pathology was found in his oral soft tissues. Dental caries was found on both primary and permanent molars. A decision was made to complete dental treatment using general anesthesia as a behavior management technique at the local children’s hospital.

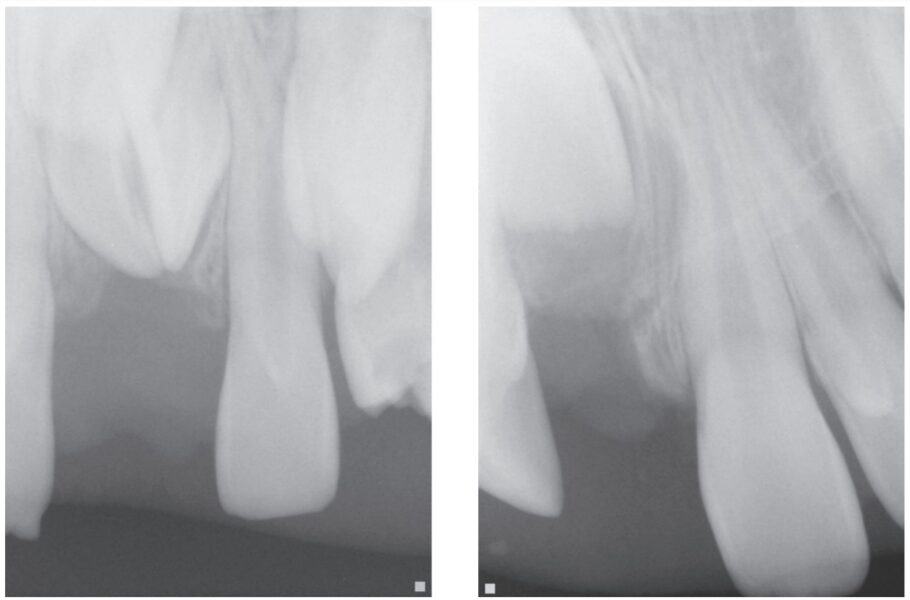

The following procedures were accomplished under general anesthesia on an outpatient basis — full mouth dental radiographs and a comprehensive oral exam. A complex odontoma was found to be the etiology of the noneruption of the maxillary right permanent central incisor (Figure 2). Since dental caries also was diagnosed, a full-mouth prophylaxis was completed. Dental caries was controlled, and teeth were restored. A 5 mm incision was made on the gingiva over the impacted maxillary right permanent central incisor, and two tooth-like structures were extracted from the right maxillary incisor area. A postoperative periapical radiograph was taken to confirm complete odontoma removal (Figure 3). Three interrupted sutures using 3-O chromic gut were placed.

At the postoperative consultation with the mother, we told her the tooth’s complete root formation might prevent its eruption. Orthodontic extrusion of the incisor was ruled out due to his behavior. A conservative approach with observation only was elected as treatment modality. This patient returned for follow-up appointments at ages 10, 11, 12, and 13. During all these visits, the maxillary right permanent central incisor had not erupted. At age 14, due to recurrent dental caries, the patient was taken to the local children’s hospital for dental rehabilitation again. During this second hospitalization, we noticed that the right maxillary central incisor was partially erupted into the oral cavity (Figure 4).

Discussion

It is well known that autism is a serious developmental disorder that impairs the ability to communicate and interact with others. Children with autism pose a challenge in terms of behavior management in the standard dental setting. Comprehensive orthodontic treatment offers clinicians even more of a challenge with these patients.

Every patient needs to be evaluated individually because a great deal of cooperation and time is required for orthodontic treatment. Parents need to understand that in severely autistic children, orthodontic treatment might not be a viable solution. Communication is paramount, and realistic expectations ought to be communicated with these children’s caretakers. This patient illustrates that a conservative approach consisting of odontoma removal was enough to allow eventual eruption of the incisor.

Conclusion

Pediatric dentists, by training and expectation are primarily therapists, but with this patient, minimal therapy produced a good outcome.

Some patients need a conservative approach, and some need orthodontic, restorative, or even prosthetic care to fulfill their needs. Read an interesting article, on space closure and doctors’ preferred form of treatment. https://orthopracticeus.com/which-is-the-best-treatment-modality-for-space-closure-orthodontic-restorative-or-prosthetic/

- Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:1313.

- Satish V, Prabhadevi MC, Sharma R. Odontome: A Brief Overview. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011 Sep-Dec;4(3):177-185.

- Katz RW. An analysis of compound and complex odontomas. ASDC J Dent Child. 1989 Nov-Dec;56(6):445-449.

- Budnick SD. Compound and complex odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976 Oct;42(4):501-506.

- Suri L, Gagari E, Vastardis H. Delayed tooth eruption: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. A literature review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004 Oct;126(4):432-445.

- Kjær I. Mechanism of human tooth eruption: review article including a new theory for future studies on the eruption process. Scientifica (Cairo). 2014;2014:341905.

- Review Article. Mechanism of Human Tooth Eruption: Review Article Including a New Theory for Future Studies on the Eruption Process Scientifica Volume 2014 (2014), Article ID 341905, 13 pages

- Strategies for treating an impacted maxillary central incisor. International Orthodontics Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2010, Pages 152-176

- Behaviour management needs for the orthodontic treatment of children with disabilities. The European Journal of Orthodontics 22(2):143-9 · May 2000.

Stay Relevant With Orthodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Gabriela Aurora Asensi, DMD, MPH, CLC, received her first dental degree from Universidad Central de Venezuela. In 1996, she completed a general dentistry residency program at Miami Children’s Hospital becoming chief resident. In 2000, she also completed the joint residency program of Miami Children’s Hospital and University of Florida. She completed the Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) degree at Nova Southeastern University in 2003. Dr. Asensi also graduated from Florida International University (FIU) with a Master in Public Health in 2021. She is a pediatric dentist in private practice in Miami, Florida.

Gabriela Aurora Asensi, DMD, MPH, CLC, received her first dental degree from Universidad Central de Venezuela. In 1996, she completed a general dentistry residency program at Miami Children’s Hospital becoming chief resident. In 2000, she also completed the joint residency program of Miami Children’s Hospital and University of Florida. She completed the Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) degree at Nova Southeastern University in 2003. Dr. Asensi also graduated from Florida International University (FIU) with a Master in Public Health in 2021. She is a pediatric dentist in private practice in Miami, Florida.